Virtual relationships can offer comfort, but watch that they don't steal your time from real-life connections

Otome games such as Love and Deepspace are taking off everywhere. For players, becoming overly reliant on the bonds formed with these virtual characters poses real-life risks, mental health experts said.

The appeal of romance-themed mobile games lies in the sense of safety, predictability and unconditional acceptance that virtual relationships can provide, a psychologist said. (Illustration: CNA/Samuel Woo)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

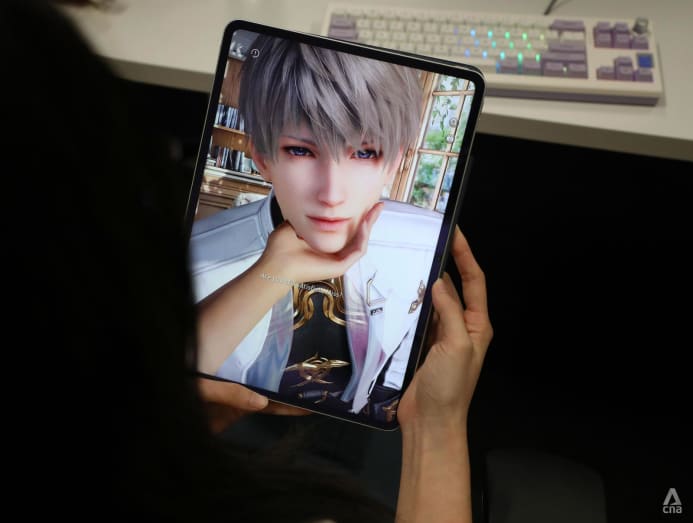

Captivated by a brooding artist and having spent much time with him, 19-year-old tertiary student Lin Yu said: "I treat it as a 'romantic level' relationship."

She was referring to Rafayel, a character in Love and Deepspace, an otome game or "maiden game". This genre of video games, targeted at females, are heavily focused on romance, where male characters, storylines and the gaming experiences cater to players' emotional needs.

What began as a casual download of the gaming application last January has now become a daily ritual of gameplay and online connection for Miss Lin.

She logs in for a short while to complete tasks, stays on longer when new chapters of the storyline are released, and saves countless pictures from the in-game photobooth. She did not want to say how much she has spent on the game, only that she felt it was worth it.

"The characters are really nice and loving," she said. "They give (me) a sense of comfort and security."

Miss Lin has even found ways to indulge in this virtual bond offline. She attends fan gatherings and even goes on "cosdates", engaging cosplayers to embody her favourite characters as they spend an afternoon together.

"It turns things into reality for us," she said, adding that many cosplayers are driven by passion rather than profit. Most of them do not charge for their time, seeing it instead as a way of celebrating the game and its community.

What was once a niche genre has now become a global phenomenon.

Otome games are quickly drawing hordes of fans and devotees. Apart from Love and Deepspace, titles such as Tears of Themis and Mystic Messenger have drawn millions of downloads across East Asia, North America and Europe.

Like Miss Lin, many young players are discovering that digital companions can feel safer – and sometimes more rewarding – than the messy uncertainties of real-world intimacy.

THE RISE OF DIGITAL INTIMACY

Game design experts said that the rise of otome games reflects how the genre has evolved. This is due in large part to how the "gacha pull" element has been deployed in modern game releases.

"Gacha pull" refers to the lottery-style system where players spend money for a random reward. This can include unlocking a new character, a cherished item or an intimate memory – all of which are designed to deepen the bond between player and character.

Mr Shamim Akhtar, who heads the immersive media and game development diploma course at Temasek Polytechnic, said: "In the early days, the gacha system was mostly about pulling cards or collecting monsters."

The real turning point, he said, came when the act of collecting turned into an emotional event, rather than a mechanical task.

"The prize itself became a full character, complete with a distinct personality, voice acting, backstory and unique visual design."

That sense of connection is reinforced by storytelling. Instead of letting players get their fulfilment on completing the gameplay at once, new chapters and events are released in instalments.

Mr Shamim said: "Modern-day storytelling and gameplay are carefully designed to work together to keep players engaged for months and even years. This episodic release creates a slow burn, making players feel that they are part of a romance or adventure that grows with time."

Mr Michael Thompson, principal lecturer at DigiPen Institute of Technology Singapore, said: "For many of the same reasons people read or watch episodic television series, once they become emotionally invested in a character, they want to see what happens next.

"Designers often milk this curiosity for extended periods of time, keeping players showing up for the next 'episode' of gameplay, or binge playing."

Together, these design choices make users feel less like they are playing a game and more like they are building real relationships with the virtual characters in them.

WHO FALLS HARDEST?

Some players are especially drawn in when real-life relationships feel uncertain.

Dr Natasha Mitter, principal psychologist at US Therapy, which provides wellness and counselling services, said: "The appeal lies in the sense of safety, predictability and unconditional acceptance that these virtual relationships can provide."

Loneliness, past trauma and difficulty forming real-world connections can heighten this pull.

Young people looking to form an identity, as well as neurodivergent players who find real-life social cues challenging, are also likelier to engage deeply in such video games.

Ms Theresa Pong, founder and counselling director of The Relationship Room, agreed that these digital relationships can make players feel "safe" because they remove the fear of rejection, judgment or conflict that often comes with real-life intimacy.

Many players turn to these virtual relationships for affection and comfort after experiencing setbacks in failed relationships.

"For them, virtual companionship offers a sense of acceptance, warmth and certainty," she said.

So how exactly do these games tap a person's emotional needs?

Dr Mitter the clinical psychologist explained: "These games are powerful catalysts for a psychological phenomenon called projection, in which (players') unresolved emotions can transfer onto the characters.

"The player isn't just bonding with code; they are, in a way, connecting with a mirror of their own inner self."

This helps explain why someone grieving a lost relationship may seek storylines of being "rescued" and unconditionally loved, playing out the healing they crave in real life.

In moderation, these games can support mental health.

For players, the games can provide stress relief, lift mood and even serve as safe spaces to explore various aspects of their personal identity or flirt without fear of judgment, Dr Mitter said.

Another benefit is the community around them. Ms Pong the counsellor said that many players feel a genuine sense of belonging, not only through the emotional connections they form with virtual characters, but also by joining groups of fellow players who share the same hobbies and interests.

In both ways, these ties can meet the human desire for closeness, acceptance and importance.

WHERE TROUBLE STARTS

However, problems arise when virtual bonds start to replace real ones.

"Games are incapable of providing genuine, long-term support," Dr Mitter warned.

"This inherent limitation can ultimately worsen feelings of anxiety, depression and loneliness when the player's needs inevitably go unmet."

Expectations for real-life relationships and interactions can also become distorted.

Real-life partners, unlike scripted characters, may not always respond predictably, and that gap can breed frustration.

For younger players, the risks are developmental. Ms Pong cautioned that if intimacy is learnt mainly through fictional relationships, they may miss out on building resilience through real-life ups and downs.

Couples are not immune either. She has seen situations where people felt like they had been relegated to "second place" behind a virtual character in receiving their partner's affections.

"Over time, this creates a drift in emotional closeness, as attention and care shift towards the digital world instead of nurturing real-life connections."

THE COST OF CONNECTION

Socioemotional effects aside, over-reliance on such games can also strain finances.

In games such as Love and Deepspace, spending is often framed as affection.

Mr Shamim from Temasek Polytechnic said: "In some cases, even the act of a successful gacha pull is framed as the character choosing to join the player."

"This subtle framing transforms a random game mechanic into a personal moment, where it feels as if affection has been returned," he added.

By conflating affection with purchase, spending money feels less like buying pixels on a screen and more like deepening a real bond. For players already seeking reassurance, each purchase can feel urgent, even necessary.

Developers know it is delicate work when weighing the scales on the variables that determine the games' desired outcomes.

"The best long-term successes are not those that extract the most money immediately, but those that build a sense of fairness and generosity," Mr Shamim said.

To achieve this, studios have introduced features such as "pity pulls", which guarantee a reward after a set number of tries. Many also provide free in-game currency through events and log-in bonuses, ensuring that even non-paying players can progress and enjoy the game.

"This balance is critical to keeping the illusion of romance alive while still sustaining the business model," Mr Shamim added.

Even so, the danger remains. When intimacy itself is tied to financial exchange, the cost can go beyond money to bring on guilt and secrecy, straining real-life relationships.

NAVIGATING BOUNDARIES AND FINDING BALANCE

All the same, mental healthcare practitioners including Dr Mitter are reluctant to write off such games as inherently "good" or "bad".

"The key lies in awareness and balance," she said.

She highlighted some warning signs:

- Neglecting responsibilities

- Showing distress or irritability when not playing

- Exhibiting secrecy and withdrawing socially

To maintain balance, she recommended setting time and spending limits, tech-free windows – intentional pockets of time where you put away gadgets and disconnect from digital platforms – as well as self-reflection ("Am I playing to enhance my life or escape it?").

Such boundaries stick best with support, Ms Pong advised. For instance, she recommended that players who are looking to scale back on their investment in such games would do well to find themselves an "accountability partner".

"This can be either someone who plays the games or doesn't. What matters most is that they understand your goals for having accountability, support healthy boundaries and can check on you regularly."

She also suggested inviting friends or partners into some gaming sessions, while making deliberate time offline to nurture real-world ties.

For players such as Miss Lin, however, the meaning of these games stretches beyond cautionary tales.

Although she is aware of the risks when virtual bonds replace real ones, she sees her online connections as proof of a more universal truth about human nature: "As humans, we develop feelings for things."

What stemmed from curiosity has become both comfort and community. And perhaps, that says less about these games and more about the people playing them.