Learning Chinese has become too difficult for kids today, and that’s not okay

Is it just too hard for kids to learn Chinese in Singapore schools? This mum-of-two explains why she thinks the answer might be yes – and why that bodes ill for young Singaporeans trying to develop a love for their mother tongue.

The writer worries that unnecessary stumbling blocks such as too-difficult vocabulary can demotivate kids in their Chinese learning journey. (Illustration: CNA/Samuel Woo)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

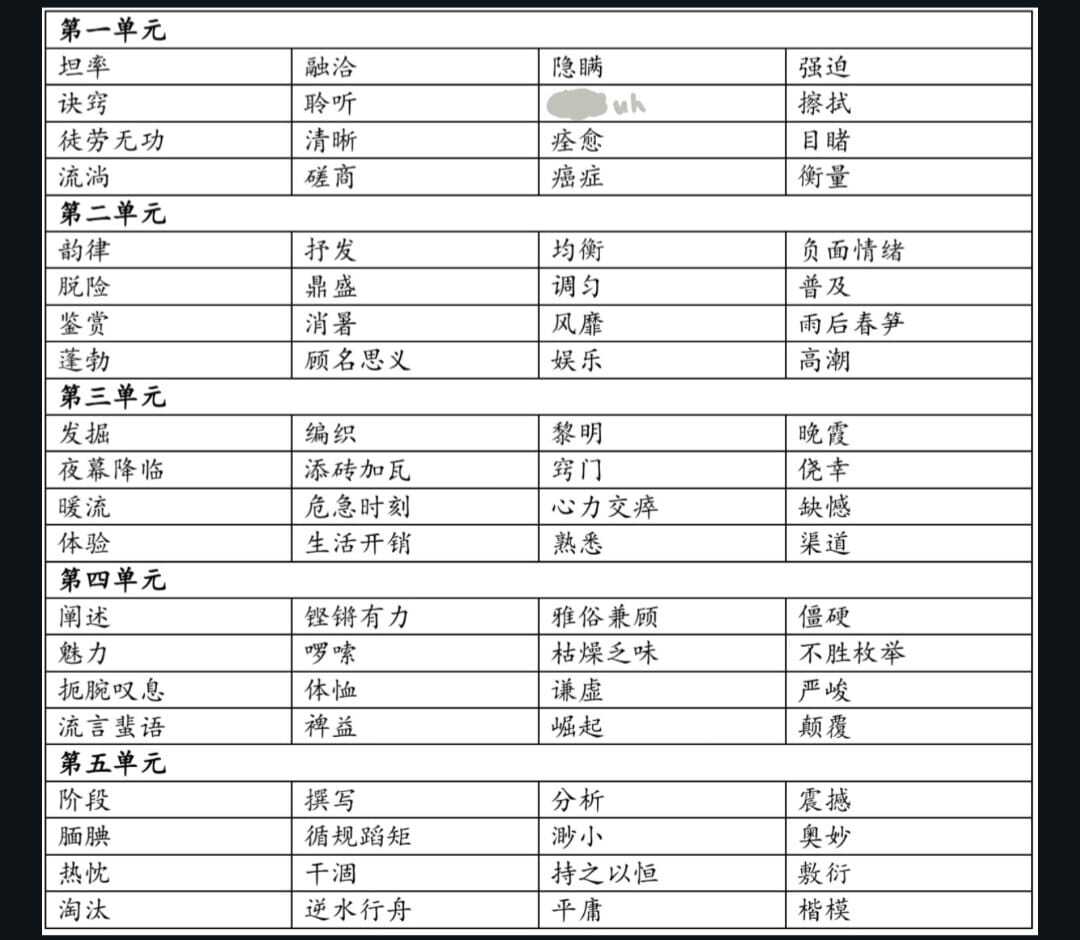

Recently, while revising for her end-of-year exams, my 15-year-old daughter came to me with a list of Chinese words, asking me to test her on them.

It had been a while since she'd asked for help. Ever since starting secondary school, she has mostly managed her studies on her own. But when she handed me the list, I wasn't surprised by the request. Rather, I was caught off guard by what was on it.

Now, I consider myself fairly proficient in my mother tongue. Not only did I grow up in a Chinese-speaking family, I consistently scored As in Chinese throughout my schooling years.

The list of words my daughter handed me was meant for her Secondary 3 cohort (she's in the International Baccalaureate programme, but the Chinese textbook they use is the same as the O-Level track). But I found myself unable to read a number of them, let alone understand them.

Even my husband, who had studied Higher Mother Tongue (HMT) back in school, found some of the words unfamiliar and difficult.

Watching my daughter struggle to recall how to write certain words or their meanings, I felt her frustration deeply. This is a child who has always been academically focused and motivated, and used to have perfect scores for Chinese spelling tests (or tingxie) in primary school.

That frustration led me to post the list on social media, wondering aloud why secondary school students were now expected to learn such advanced vocabulary.

The response was overwhelming.

Many parents messaged me about similar struggles their children face learning Chinese in school. Many more said that they themselves couldn't understand some of the words on the list I had posted.

CAN WE AIM "TOO" HIGH?

A friend who is a Chinese writer explained that many of the words are advanced versions of simpler terms. The advanced versions are more poetic and beautiful, great for literature – but not quite practical for everyday use.

"In reality, we'd just use the simpler forms," she said.

Can Singapore’s educators and parents hope that we are nurturing some children to one day become acclaimed Singaporean Chinese authors or poets like You Jin or Dan Ying? Sure, but let's be honest: Most of our kids are just trying to pass their exams.

One parent told me the words in the list are considered primary school level in China. That may be true, but Mandarin is the dominant language there.

Meanwhile, Singaporeans of all races and ethnicities are increasingly more comfortable in English than in their mother tongue. Many of my own Singaporean Chinese friends struggle to hold a full conversation in our mother tongue without inserting English words.

I'm not saying that our academic standards should remain frozen at what they were 30 years ago when I was a secondary school student.

But our Chinese standards are clearly not as high as our China counterparts. Why make that the baseline for comparison?

KILLING THE JOY OF LEARNING

Academic pressures are part and parcel of Singapore schooling life, but I worry that the current language expectations in secondary school are so high that they’re killing students' interest in their mother tongue.

My daughter used to enjoy writing Chinese compositions in primary school. Her stories were unique, with hooks and bittersweet endings, and her teacher often used them as model essays, even though she didn’t rely on flowery language or colourful idioms. She was always excited to write in her mother tongue.

But in secondary school, the focus shifted.

Her creativity was no longer enough. The emphasis turned to writing within strict parameters and memorising idioms to meet grading rubrics.

She put in the same effort, but received only lukewarm results, both in terms of grades and feedback from her teachers that made her feel like she was always falling short.

She stopped enjoying writing in Chinese altogether. Now, she no longer looks forward to Mother Tongue as a subject at all. This isn't just our experience.

Another parent told me that her daughter, despite putting in tremendous effort for HMT, failed a weighted assessment for the first time. "She just hopes to pass,” the mother said. "It doesn't help that the school sets such difficult papers."

One secondary school student told me that revising for his end-of-year Chinese exams was "absolute torture".

My husband and I have, like many parents in the same boat, started telling our daughter it’s okay not to score well in Chinese – just aim to pass.

After all, when our kids are working so hard but still falling short of impossible expectations, sometimes the kindest advice is to aim to clear the lowest possible bar. Perhaps they're better off spending their limited time working on subjects where they have a much higher chance of seeing better returns.

ENCOURAGE INSTEAD OF DISCOURAGE

Instead of pushing our kids to match their counterparts in China or expecting them to become Chinese classicists and poets, can we first help them develop a love – or at least a tolerance – for the language?

Another Chinese writer friend of mine noted that such unnecessary stumbling blocks can demotivate kids in their learning journey.

"It really takes the joy out of learning when students have to memorise terms they’ll never use in daily writing or conversation," he said. And I couldn't agree more.

So instead of asking children to memorise obscure and poetic terms they'll rarely use in daily life, why not let them learn the kind of Chinese that feels relevant to their world. This might come from local news reports, TV shows, songs or novels, even if these are considered primary school level in China.

Rather than restricting students to rigid rubrics, could we give them more opportunities to use the language in more creative ways – such as writing informal journals or performing skits – which can make learning feel less like a test and more like an exploration?

Instead of focusing on students' inability to meet inflexible standards, it could also be beneficial to give them small wins and encouragement. Feedback like "This is a great story idea" or: "You’ve improved" can go a long way towards affirming a child’s effort, and inspiring them to want to put in even more.

In contrast, constantly failing them or reminding them they're not meeting an arbitrary standard only chips away at their self-worth. It teaches them that no matter how hard they try, they'll never be good enough.

And when that message is repeated often enough, the love for learning fades – not just for Chinese, but for any subject where joy is overtaken by dread.

If we truly want our children to grow – not just as students, but as confident, curious individuals – then it's worth rethinking how we support their learning.

Recently, Singapore’s new Education Minister Desmond Lee signalled a shift away from the "education arms race", calling in parliament for reforms that reduce exam pressure and broaden definitions of success.

In 2024, Singapore’s Ministry of Education announced initiatives – including more opportunities for secondary school students to take up HMT and a mother tongue language reading programme in primary schools – to "uphold bilingualism" in the education system, and help students learn and use their mother tongue as a "living language".

While we are rethinking how students learn and grow, surely we can also rethink how we nurture their relationship with their mother tongue – not just through grades and memorisation, but through relevance, creativity and connection.

Vivian Teo is a mum of two. She is also a freelance writer, children’s book author and owner of a parenting and lifestyle blog.

If you have an experience to share or know someone who wishes to contribute to this series, write to voices [at] mediacorp.com.sg (voices[at]mediacorp[dot]com[dot]sg) with your full name, address and phone number.