IN FOCUS: Are Chinese dialects at risk of dying out in Singapore?

Dialects are not just a form of communication but convey cultures, identity and family ties, proponents say. But with fewer Chinese Singaporeans speaking these languages, is there value in learning them?

(Illustration: Clara Ho)

SINGAPORE: For years, Brandon Seah had a nagging thought at the back of his mind – to learn Teochew properly one day.

He had picked up simple phrases from his grandmother when he was young. But like most of his generation, the use of predominantly English and Mandarin in school and at home meant that he never quite mastered his dialect, as much as he wanted to.

“It’s the first language of your grandparents but because it’s not yours, it becomes hard to have proper conversations with your own grandparents or even within the family. If you think about it, it’s actually quite strange.

“We think it’s ‘normal’ because we all grew up with this experience but if you go to other countries or communities, it’s not,” said the 36-year-old.

“So for the longest time, I told myself that someday I will learn it properly.”

But as work took him overseas, there was never really a right opportunity for formal lessons.

There was also a lack of suitable learning materials for Teochew, such as a standard textbook. Any written guides available were mostly in Mandarin, for native speakers in China who already have a certain level of proficiency.

Other beginner materials focused on essential vocabulary and phrases and did not provide guidance on forming longer sentences. Various romanisation systems were used, making it difficult to learn pronunciation, Mr Seah said.

Around 2018, the Singaporean realised that if he wanted to learn his dialect, he just had to “get started”.

He began searching for learning materials online, including academic papers, in his free time. He also found audiovisual recordings from the National Archives of Singapore, which he described as useful and a tad nostalgic as “they sounded exactly like (his) grandparents”.

“I was transcribing short excerpts from these online recordings, finding all the grammatical structures and learning from there,” he recalled.

“After some time, I realised I had a lot of notes written up for myself. Why not tidy it up and share it with other people? By then, COVID-19 happened, and it became a bit of a ‘lockdown project’.”

Learning guides for other dialects, such as Cantonese, taught him how to categorise his notes according to topics such as numbers, terms of address and different pronouns. In May 2020, nearly two years after embarking on his dialect journey, Mr Seah launched the Learn Teochew website.

“I wouldn’t say I’m very eloquent in Teochew now. I’m just a very motivated learner,” Mr Seah said with a laugh.

He is not alone. There has been “steady” interest in learning dialects in recent years, with some young Singaporeans taking steps to preserve and promote these Chinese languages for reasons such as family and reconnecting with their heritage, said academics, language schools and clan associations that CNA spoke to for this article.

Still, the reality is that the speaking of Chinese dialects in Singapore is on the decline.

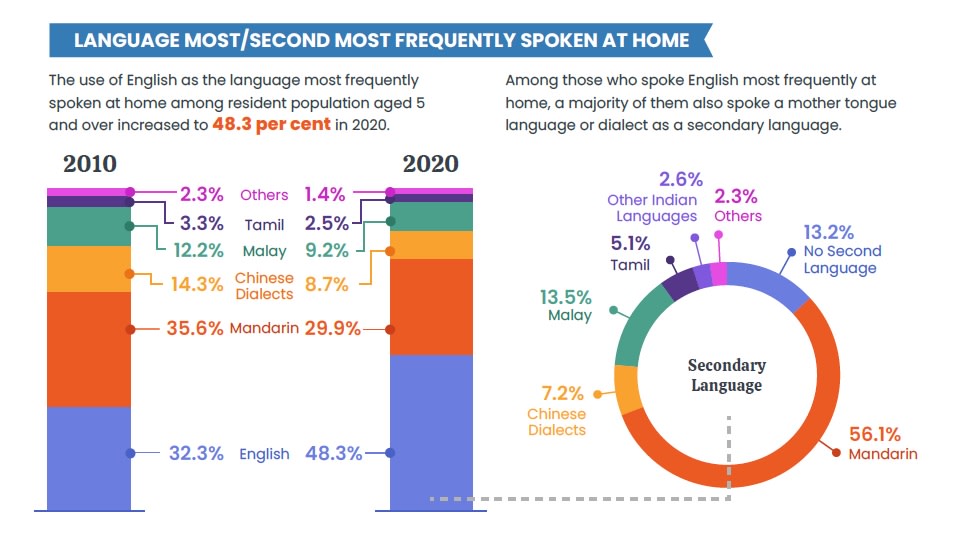

Only 8.7 per cent of residents aged five and above used dialects as the most common language at home in 2020, a drop of 5.6 percentage points from 2010, based on the latest population census.

More households now use English as the most common language – at 48.3 per cent in 2020, versus 32.3 per cent in 2010.

Even among those who spoke a second language at home, only 7.2 per cent spoke Chinese dialects.

This waning use of dialects will likely continue.

Mr Sew Jyh Wee, a lecturer at National University of Singapore’s (NUS) Centre for Language Studies, said: “As youngsters shy away from speaking their dialects due to practical reasons like not having the exposure and environment to do so, my two cents’ worth is that dialects are going to slowly fade away.”

A DWINDLING GROUP

Currently, the most spoken dialects in Singapore are Hokkien, Cantonese and Teochew.

Among those who spoke Chinese dialects at home, the latest population census found that around half spoke Hokkien. About a quarter used Cantonese, while just under one-fifth spoke Teochew. The rest spoke other Chinese dialects.

One big factor behind the dwindling use of dialects is the Speak Mandarin Campaign first rolled out in 1979, said associate professor of linguistics and multilingual studies Tan Ying Ying from the Nanyang Technological University (NTU).

The campaign was launched with the aim of having Mandarin replace dialects as the unifying language of Chinese Singaporeans who were then speaking different dialects. There was economic value in being proficient in Mandarin, while the impracticality of mastering two languages and a dialect would also hamper Singapore’s bilingual policy, the Government said then.

In his opening speech for the campaign on Sep 8, 1979, then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew urged Chinese parents to stop speaking dialects at home and switch to Mandarin to help lighten the learning load of their children, according to the Straits Times.

Armed with “strong pragmatic reasons” and multiple channels such as a theme song and posters driving home the message, the Speak Mandarin Campaign was “incredibly successful” and delivered a “huge blow” to the use of dialects, said Assoc Prof Tan.

“After a while, it gets drummed into you that if you have to learn a language, learn the one that gets you going. If you are a parent or a grandparent, educate your child well,” she added.

“In a very pragmatically driven society like Singapore, this kind of messaging works. And that alluded the status of Chinese languages to just dialects – in that it’s not that important and you don’t have to learn them.”

Assoc Prof Tan recalled how, as a child, she was made to speak Mandarin to everyone at home, except to her grandmother who spoke only Teochew.

“Even my grandfather actively learnt Mandarin because of my mother’s ‘Don’t speak Teochew’ rule … We are looking at a whole generation believing that dialects were not good for their children.”

This, according to Assoc Prof Tan, resulted in an “intergenerational language loss” which inevitably paved the way for lesser interest and competency in dialects among the young. This has also led to difficulties in communication between the young and seniors in their family who only speak dialects.

The Government has reiterated that its language policy was necessary.

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, for instance, said in 2014 that it is not pragmatic for dialects to be used more widely and mastered alongside English and Mandarin.

While he understood the desire to protect dialects as an important part of the Chinese culture, Singapore introduced its bilingual policy after careful observation and finding that it is difficult for most people to master English, Mandarin and dialects at the same time.

“This principle has not changed,” Mr Lee was quoted as saying in a Straits Times report.

The trade-off between emphasising bilingualism and sacrificing dialect has allowed Singapore to maintain good standards in English and Mandarin, he added.

However, there is still room for dialects in Singapore, said the Prime Minister. This is why news is reported in dialect on one radio channel and clan associations run classes in dialects. The Government is also prepared to use dialects in special circumstances such as explaining key policies to seniors, he said.

THE ROLE OF DIALECTS

But with fewer speakers, will these distinctive Chinese languages eventually fade away?

Earlier this week, Health Minister Ong Ye Kung described dialects as having the human touch. Speaking in Hokkien and Mandarin at an anniversary dinner of the Singapore Ann Kway Association, he said even if dialects do not have much commercial value, they can still bring people closer together.

Those that CNA spoke to said dialects go beyond just a form of communication and that they convey cultures, identity and family ties.

Mr Jeremiah Soh, marketing and publicity manager of the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan Cultural Academy, said each dialect brings with it traditional Chinese values, unique customs for festivals and significant milestones in life, art and culture, as well as cuisines.

“It is part of what makes Singapore multicultural and so unique,” he said.

For Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan’s president Chan Kian Kuan, dialects still have a utilitarian value for doing business in parts of China. But an even bigger value lies in the cultural heritage they embody.

That is why he thinks it is “right” for authorities to reinstate dialect groups in birth certificates.

The dialect groups of a child's parents were left out from the new digital birth certificates in Singapore's transition from physical birth certificates this year.

The Immigration and Checkpoints Authority (ICA) said in August that the information was left out as it was “not necessary for policy and other administrative needs”. But dialect groups continue to be registered by ICA and the information is available on Singpass.

ICA eventually decided to include dialect groups in digital birth certificates in response to “feelings that have been expressed on the matter” and “several queries”.

Commenting on the issue, Home Affairs and Law Minister K Shanmugam noted that dialect groups are important to many people.

“It relates to culture, it relates to heritage, which many people hold dear and would want to continue to see safeguarded, and removing the information makes people concerned. These are real concerns that must be acknowledged,” he said.

Meanwhile, dialect-speaking individuals, mostly elderly, remain. This particular group may find it difficult to connect with a society that is rapidly moving away from the languages they are most familiar with, said Mr Eugene Lee, co-founder of language school LearnDialect.sg.

He recalled a volunteering experience at a nursing home many years back where seniors were hesitant or unable to voice their needs due to language barriers. This spurred him to set up the language school in 2018, with the initial aim of providing dialect classes for healthcare workers.

Mr Lee, who grew up speaking Teochew with his family, said the place of dialects in a society should be a sentimental one – closing the gap between generations and passing on family stories.

“Dialect is not only a language. It is the stories that all our ‘ah ma’ (grandmothers) and ‘ah gong’ (grandfathers) can give us. These are what, from my personal view, make dialects worth preserving.”

“IF PEOPLE DON’T DO ANYTHING, IT WILL DISAPPEAR”

Melissa Tan is one young Singaporean hoping to better understand family conversations and, more importantly, stories told by her grandmother.

With her understanding of Hokkien limited to basic greetings such as “jiak ba buay” (“Have you eaten?”), the 22-year-old said her own dialect felt like “a secret language” during family gatherings.

“It is frustrating because my grandmother is sharing some of her stories with my parents, but I don’t understand. I keep having to ask them to translate for me, and sometimes they give up,” she said.

When her parents said they would be unqualified teachers as they did not speak “proper” Hokkien, Ms Tan decided to attend classes with LearnDialect.sg in June. For eight hours over two weekends, she learned how to count, tell the date and time, and expanded her Hokkien vocabulary to include food and idioms.

These days, she practises speaking Hokkien with her family and while ordering food at coffee shops. She intends to surprise her grandmother with a “simple conversation” during the coming Chinese New Year.

“I'm hoping that (she) will be proud of my improved Hokkien standard.”

Mr Lee noted that family is usually a key motivation for young learners in their 20s. His school, which offers Cantonese and Teochew classes as well, also sees professionals in the healthcare and social work sectors who hope to be able to better communicate with dialect speakers at work.

Clan associations have observed similar motivations among those attending their dialect courses.

Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan, which holds basic and intermediate Teochew classes for both children and adults, said it takes in students regularly throughout the year, with an average of about 10 students in each class.

Demand has also been “steady” at the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan Cultural Academy, which has been conducting conversational Hokkien lessons since 2014 and sees students ranging from their 20s to 60s.

Over at NUS, Mr Sew said dialect modules were first offered in 2020 following a student’s request via the university’s design-your-own-module initiative.

“The very first class was for Hokkien. I was given a room for 35 students but in the end, we had to shift to one that hosts 40 people. The enrollment was a surprise.”

Since then, Mr Sew has followed up with modules for conversational Cantonese and Cantonese pop songs. Sign-ups have remained encouraging, he said, citing factors such as students spending more time at home with their grandparents during the pandemic and the availability of some dialect content on television.

But even so, enrollment numbers may not suggest “real lasting interest”.

“Learning doesn’t stop after you finished a class. Learning also does not have to be done in schools,” said Mr Sew. “But it’s a personal choice whether youngsters want to keep learning dialects or invest their time and effort in other things like programming and data management.”

“Social media and pop culture are also fighting for the interest of these youngsters, and it is up to them to associate themselves with languages or cultures that appeal more to them,” the NUS lecturer added.

Asked about the future of dialects in Singapore, most gave a bleak prognosis.

“If people don't do anything about it, (dialects) will disappear,” said Mr Chan from Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan.

Having more dialect content in mainstream media will help, he added, pointing to his own experience of picking up Cantonese from Hong Kong movies and English from songs.

Clan associations, which total to around 200 in Singapore, will also continue to do their part to “connect society with dialects”. For one, Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan has been trying to reach out to the younger generation through activities such as sports and beauty pageants, as well as taking its Teochew Festival virtual last year.

But at the end of the day, it is “up to individuals to preserve their dialects and culture”. This must start from home, Mr Chan stressed.

Likewise, Mr Soh said it takes “the society’s effort” to keep dialects going. As part of that, the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan will continue to organise activities to preserve and promote Hokkien and its culture.

For instance, the association had a three-day festival earlier this month which featured Hokkien cuisine, exhibitions and cultural performances.

Turnout at the festival was encouraging, said Mr Soh, adding that he was heartened to see many young parents with children. The association also received “quite a few” enquiries for its Hokkien classes from young Singaporeans as well as foreigners.

“There was a young American who, after stopping by the festival, said he is very keen to learn Hokkien,” a beaming Mr Soh said.

“Obviously, he does not need to use Hokkien in his communications with people. He was just interested to find out more and learn it like additional knowledge. I think that’s what we are also happy to see.”

CAN TECHNOLOGY HELP?

Can technology offer a solution?

In October, Facebook owner Meta unveiled an artificial intelligence system which can translate between spoken Hokkien and English in real time.

The technology giant described this as the first speech translation tool for a primarily oral language like Hokkien, which lacks a formal writing form and large quantities of paired speech data. There are also few human English-to-Hokkien translators, making it difficult to collect and annotate data.

To get around these challenges, Meta researchers used text written in Chinese, which is similar to Hokkien. The team also worked closely with Hokkien speakers to ensure that translations are correct.

Currently, the artificial intelligence system remains a work in progress and can translate only one full sentence at a time. The eventual goal is to allow for simultaneous translation, not just for Hokkien but also other languages to break down language barriers between people in different parts of the world.

Meta also hopes its tool can help to bridge communication gaps between generations and prevent some languages, especially those without a standard written form, from dying out.

The announcement has since generated some interest. Dialect speakers told CNA that such technological creations can be helpful, but they will have to take note of variants of the same dialect spoken in different parts of the world.

Hokkien, which has a history of more than 1,700 years, is spoken by about 46 million people in parts of China, Taiwan, and among the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asian countries like Singapore, Malaysia and the Philippines. The dialect differs in tone and vocabulary across these communities.

Take the example of Singapore where Hokkien is sometimes infused with words borrowed from other languages, such as “suka” which means “like” in Malay.

“Locally, we say ‘Wa suka li’ to mean ‘I like you’ in Hokkien but in other parts of the world, it is ‘Wa ga yi li’,” Mr Lee said.

“So artificial intelligence is helpful but when you have so many variants of Hokkien, to what extent will such a tool be relatable? Will it be customised according to where the speakers are from?”

For Mr Seah, technology has enabled him to document his own journey with learning Teochew and connect with like-minded people around the world. Followers on his Learn Teochew Facebook page come from the United States, as well as different parts of Europe and Asia.

Earlier this year, the Singaporean met up with a group of heritage speakers like him in Paris.

“These are people with similar experiences growing up but completely different backgrounds. Their parents came from Cambodia or China and later moved to Europe so they grew up speaking French or English. But they are interested in Teochew because it’s their parents' or grandparents’ language.

“In the past, it would have been quite difficult to reach out to so many people with the same interest and you would have remained in your own silo. Now even from so far away, we are communicating,” he said.

Mr Seah continues to finesse his online guide in his free time. His latest addition involves information about the dialect’s centuries-old art form, the Teochew opera.

“For me, Teochew is the sound of my childhood, the sound of visiting a relative’s house during Chinese New Year and the sound of home,” he said.

“For my part, I try to document what I know and what I’ve learned. Maybe it will be useful to someone someday.”