Commentary: Does it matter if your parent’s dialect group is not on your birth certificate?

It is not dialect per se that is important, but what that dialect means to an individual and to his familial group, says award-winning author Josephine Chia.

People wearing face masks cross the road in Tampines in Singapore on Feb 25, 2022. (Photo: CNA/Gaya Chandramohan)

SINGAPORE: I must admit that I reacted with joy when Law and Home Affairs Minister K Shanmugam said that the dialect field on digital birth certificates would be reinstated.

I am bound to rejoice. I am of the Merdeka Generation, a generation of Singaporeans born in the 1950s. Like the Pioneer Generation, we grew up in Singapore speaking our own dialects. Even as a Peranakan, who converse in Baba Patois at home, our patois is a mixture of Hokkien (and Teochew), interlaced with Baba Malay words.

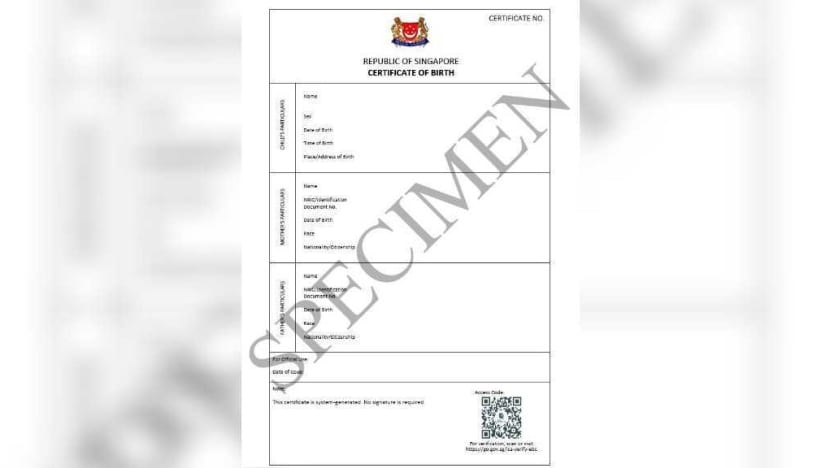

The initial exclusion of parents’ dialects from the digital birth certificates made some people concerned. These are concerns that need to be addressed.

It is not a dialect per se that is important, but what that dialect means to an individual and to his familial group.

RECOGNISING THE RICHNESS OF DIFFERENT DIALECT GROUPS

After “feelings” were expressed on the matter, the Immigration & Checkpoints Authority will be reinstating the dialect field in digital birth certificates from Sep 1.

This shift in thinking is a positive one. The Government is recognising the fact that different dialect groups have their own intrinsic culture and mores that have supported and enriched people’s lives for millenniums.

We are all aware that the different dialect groups originated from the different provinces of China. When the immigrants travelled to our island, they brought with them their own dialect, customs and culture. It is obvious that we do not need to adhere to customs that are outdated, irrelevant or divisive to our 21st-century life. But we can certainly celebrate each dialect group’s uniqueness.

Besides unique customs and mores, even the foods are different; each dialect group expressing their culinary expertise in various ways. Hokkien mee is different from Hakka noodles, and Teochew porridge is not the same as Cantonese porridge. They are all delicious in their own right.

For many years of our lives, my Peranakan mother never failed to wake my siblings and I on our birthdays with a traditional Teochew custom - a steaming bowl of sweetened mee sua with a boiled egg. Mee sua is a thin vermicelli wheat noodle. In most Chinese dialect groups' culture, long noodles represent longevity and that it is why it’s always served on birthdays.

Mee sua is often eaten as a savoury, soupy dish with slices of pork or meatballs. But for the Teochew, sweetening the noodles is symbolic of wishing a sweet life of happiness and success to the birthday girl or boy.

I have never had a sweet tooth, so I cringed at the disparity of taste. I would make a face, and my mother would admonish me, saying, “Don’t you want your life to be sweet?” It’s a no-brainer of course. So, I would force the over-sweet noodle and over-sweet egg into my mouth.

I remember those childhood days with warm fondness. This is the magical stuff of culture. It is something sewn into the fabric of your being. And our first dialect (or language) provides that foundation.

Related:

DIALECT IS PART OF CULTURE

As Mahatma Gandhi said: “A nation’s culture resides in the hearts and in the soul of its people.” Culture might not seem essential for the building up of a nation but it’s something that grows and blooms from the heart.

Dialect is part of one’s culture. It contributes to the racial identity of that person. To amputate a person of his dialect is to remove an integral part of his being. It is a travesty of the human spirit.

How we address our parents, siblings and relatives in our dialects reflects the hierarchy of the family tree; the status of the person is clearly annotated unlike the general “aunty” and “uncle” we use these days.

Young people in Singapore sometimes find it hard to ascertain their own identity. This is the result of our modern lifestyle where we are interconnected daily with the rest of the world. We get exposed to Western culture and values as our own culture is being denuded.

So, in stating dialect groups on digital birth certificates, we are reclaiming our own unique cultural identity.

The most wonderful aspect of being Singaporean is that we exist in harmony and celebrate our differences by expressing our own unique culture. Amazingly, this cultural focus does not alienate us from other racial groups, unlike in restless communities elsewhere. It is not mere tolerance but a healthy respect and regard for our colourful ancestry.

IDENTITY IN CULTURE

When I lived in the UK for well over 30 years, my culture and heritage took on a momentous significance in answering my question “Who am I?”.

I explored this existential angst in my novel When A Flower Dies. Goldie, one of three granddaughters to an old Peranakan lady, had struggled with her identity for many years.

She rebelled against the general norm, and unlike her sisters who were a successful doctor and accountant, she floated through her existential crisis. She purposely dressed in total black, with metal rings and ear and nose studs.

It was only after she spent more time with her grandmother that she began to appreciate her Peranakan culture. Eventually, she pondered the importance of culture:

“What is culture all about? Does culture contribute to who she is?

"She looked at herself in the mirror and the thought of her belonging to this featureless global youth existing on a diet of part Western values, raised on Western pop and knowing no Asian culture deeply, engaging in impersonal communication through emails, blogs and social media seemed colourless, when her own inherited culture was so rich and vibrant.”

When we value our heritage and culture, we project from a firm foundation and strong sense of identity.

Josephine Chia is an award-winning Peranakan author. Her book, Kampong Spirit, Gotong Royong, Life in Potong Pasir, won the Singapore Literature in 2014. Her young adult novel, Big Tree in a Small Pot won the Singapore Publishers Book Awards in 2019.