‘We can’t continue to worry’: Japanese surfers ride waves near Fukushima nuclear plant

Residents of the tiny coastal town of Nahara hope to attract visitors back by demonstrating that the seawater is safe – by holding a surfing contest.

Beach-goers enjoy themselves on Iwasawa Beach in Fukushima, Japan.

FUKUSHIMA: As Japan begins releasing treated radioactive water into the ocean, locals in Fukushima are bracing themselves for potential backlash.

But in the region’s eastern coastal town of Nahara, some residents are working to placate such concerns.

They hope to attract visitors back to town by demonstrating that the seawater is safe – by surfing at the Iwasawa Beach, just 20 km away from the crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant.

TOWN BRINGS BACK SURFING CONTEST

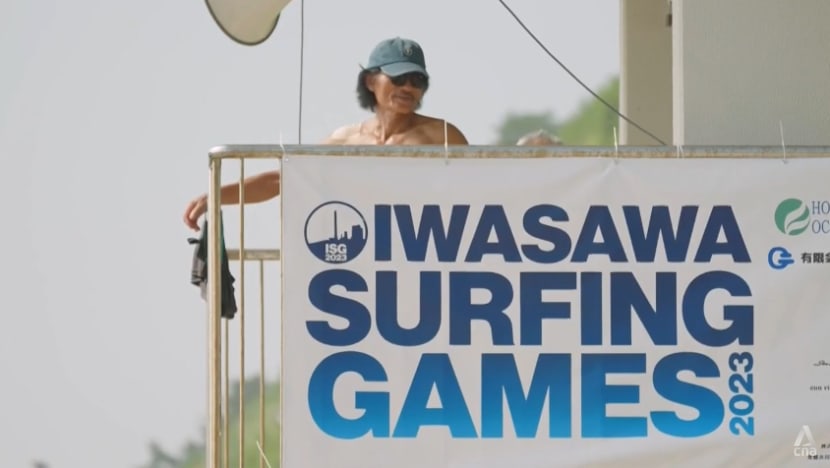

Last Sunday (Aug 20), surfers from all over the country and overseas descended upon Nahara for the Iwasawa Surfing Games, a surfing competition held for the first time since the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster.

About 190 surfers registered for the event, double the organisers’ expectations.

Iwasawa native Kentaro Yoshida, who brought the games back after the beach reopened last year, said the event is an important milestone for locals.

“I started surfing when I was 15. I was born and raised here in Iwasawa so I have been practising here for a long time. I was participating in the competition that was held here for 25 years, before the disaster struck,” he told CNA.

Mr Yoshida’s family runs hotels and an inn nearby, and he has seen first-hand how the local community has been hit hard by the disaster.

At its peak, over 164,000 Fukushima residents from Nahara and nearby coastal cities, towns and villages had to abandon their homes as the area became uninhabitable.

“When the disaster hit, local residents were gone. Many were evacuated. They had a tough time. So I thought of reviving and planning this competition that has had a 25-year history for them,” said Mr Yoshida.

Surfers taking part in the contest said they were not just showing off their skills or doing it for the love of the sport – they were also making a statement.

They said that by braving the waves, they can show others that the seawater is safe to swim in.

“I am worried. But we can’t all continue to worry,” said former national surfing champion Tetsuya Nakamura, who was competing in the event. “We should all go into the water and help draw a crowd.”

TREATED WASTEWATER RELEASE

The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant is right along the coastline, less than an hour’s drive north of Iwasawa.

On Thursday, utility firm Tokyo Electric Power Co (Tepco), operator of the wrecked nuclear plant, started the controlled release of treated and diluted radioactive wastewater into the Pacific Ocean.

This comes more than 12 years after the March 2011 nuclear meltdown in the plant. Three of its reactor cores melted and radiation was released into the atmosphere and ocean, after a 9.0-magnitude earthquake and subsequent tsunami devastated towns and villages.

Currently, more than 1.3 million tonnes of contaminated water is stored in over 1,000 steel tanks on the site.

The water will initially be disposed of in smaller portions, with additional testing conducted on seawater and fish near the plant.

The Japanese government has said the treated water from Fukushima Daiichi will have a negligible impact on the environment. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) has also given it the green light, saying it meets international standards.

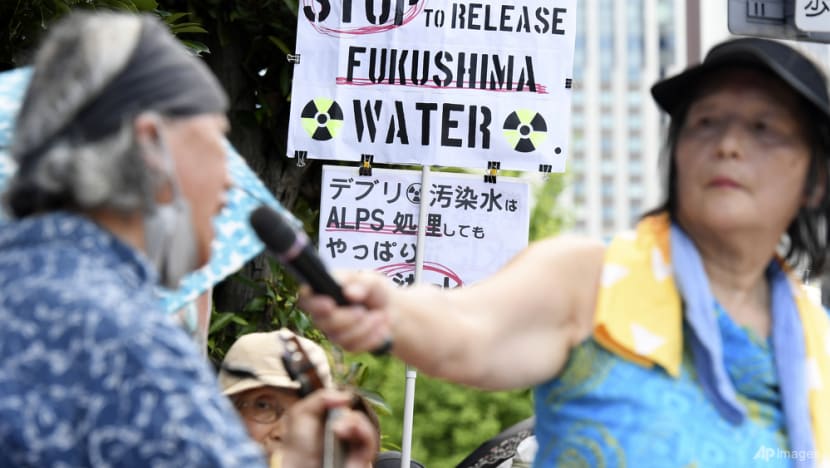

However, the move has angered people both at home and abroad.

China has been vocal in criticising the wastewater release, calling it “extremely selfish” and lodging a formal complaint. It has also imposed bans on all seafood imports from Japan.

Local communities living near the site have expressed concerns about contamination, while fishing groups are worried that consumers will avoid buying their seafood.

Related:

WORRIED LOCALS

In Nahara, some locals fear that the disposal of the treated radioactive water into the ocean could spell trouble for them, making the town once again untouchable in the eyes of beach-goers.

The government has been making efforts to ease their concerns.

Armed with pamphlets and a model of the plant, an intergovernmental liaison officer was at the surfing competition to explain the move to both locals and visitors.

Mr Sorato Nakamura, from Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, set up a booth to explain how the wastewater will be discharged, and why there is minimal impact on humans and the environment.

“Decommissioning is expected to take a very long time. With both locals and out-of-towners gathering here at this surfing competition, we would like to provide a thorough explanation to everyone,” he said.

With the decommissioning of the damaged power plant expected to take up to 40 years to complete, it will take a generation before Japan and the world can move past the fallout from the nuclear disaster.

Meanwhile, residents in the coastal area of Fukushima are doing all they can to ensure that their towns keep their reputation above water and not fall back into the economic slump they experienced in the disaster’s aftermath.

For Nahara and its surfers, they hope the surfing competition can become an annual event. They are looking at hosting the contest again next year, saying they hope that by then, the stigma associated with Fukushima and the wastewater discharge would have faded.