The village with dolls but no children – and Japan’s existential crisis

Its population ageing and declining, Japan must let go of some of its deep-set traditional values – if it wants to avoid an economic crisis. Insight investigates.

Tsukimi Ayano, 69, made these live-sized dolls to inject life back into the village of Nagoro.

JAPAN: In the village of Nagoro in western Japan, there are no cheerful voices or laughter of children playing on the streets.

The school, the bus-stops and even the streets are eerily quiet. That’s because there are no more children in this community where the last school closed in 2012.

Tsukimi Ayano, 69, is one of only 27 residents remaining. To inject some life back into the village, she created life-sized dolls and scattered them all around the community.

They dot the landscape – along the streets, outside empty storefronts, clustered in the defunct schoolroom, like a scene from a creepy movie set.

“Some (of the dolls) resemble people who used to live here or passed away,” said Ayano. Once a thriving village of 300 folks, Nagoro faded after residents died or moved away looking for employment. The youngest villager today is 55 years old.

“I think not just our town but other towns, too, must be facing an ageing or decreasing population,” said Ayano.

Nagoro reflects the demographic crisis affecting the entire country today. With a low birth rate and high life expectancy, Japan’s population is projected to shrink by almost a third by 2065.

Already, it has been declining for 10 years in a row – in 2017, for instance, the 900,000 babies born fell short of the 1.3 million people who died – and this spells serious trouble for Japan’s economy.

While the government has been trying to bolster the workforce by opening the doors a bit wider to foreign workers, and by encouraging women to work, the programme Insight asks if these measures are too little, too late. (Watch the episode here.)

AVERSE TO IMMIGRATION

As of this year, Japan has 127 million people, down about 430,000 from the previous year. This is the largest drop since the demographic survey by the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication began in 1968.

Over the years, numerous reform measures to boost the birth rates have been tried, including free early childhood education and the opening of more preschool and day care centres.

Yet, birth rates continue to slide, and the labour shortage grows ever more acute. Last year, there were 161 jobs for every 100 job-seekers.

READ: Japan's labour shortage hits 45-year high

Recently, in a major policy shift, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s government enacted a law to let in more foreign blue-collar workers, and allowed some to stay for a longer period of five years.

In April, Japan accepted some 40,000 workers from overseas in 14 fields facing acute shortages, including nursing care, IT, agriculture and construction.

READ: Japan opens door wider to foreign blue-collar workers despite criticism

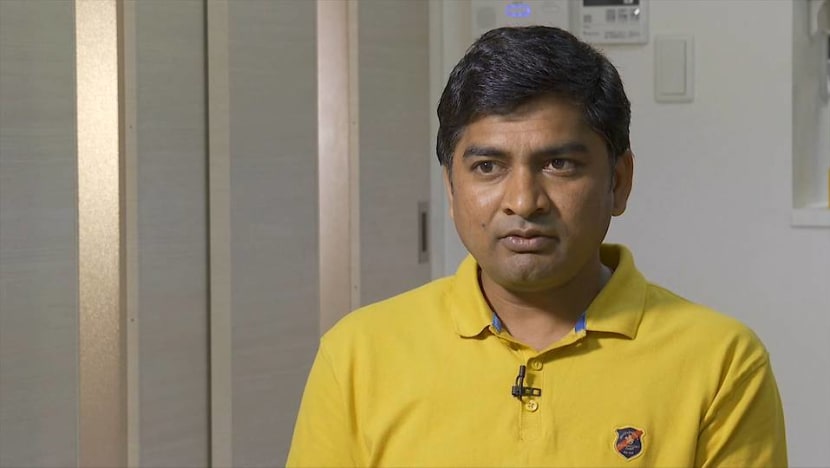

Nitin Chaudhari, 32, is an Indian national who came to Japan in 2016 to look for fresh opportunities. Now working as an IT engineer with a large Japanese company, he said trying to fit into the local work culture was challenging.

The Japanese generally do not speak English – that fact, and the typical long working hours, have tended to deter foreigners from working in Japan. Nitin had no choice but to pick up Japanese.

“Coming to and settling in Japan is difficult initially,” he said. But he appreciates that his Japanese colleagues have been making the effort to make foreigners like him feel welcome, such as learning English.

The reality is, Japan has always been proud of the homogeneous nature of its society, and racial diversity has never been its hallmark. It has yet to fully embrace the idea of large-scale immigration.

Professor Takao Komine, from the faculty of regional development at Taisho University, said that while the number of foreign workers is increasing, it’s still difficult to accept them on the same terms as the Japanese.

For example, foreigners are accepted in as trainees, but actually, there are many cases of them being used as cheap labour,

he said. “The government is trying to change things, so gradually we will see more professional foreign workers coming into Japan.”

It is also very difficult for foreigners to become permanent residents or to bring their family to Japan. This means that many, after learning the trade here, have to return to their own country, said Dr Xing Xia, assistant professor of social sciences at Yale-NUS College.

Over the next few years, the government plans to accept around 340,000 foreigners – but experts say this won’t be enough to make up for the declining population.

WATCH: Is Japan a dying country? (7:55)

CAN WOMEN WORKERS SAVE JAPAN?

Prime Minister Abe, however, has another trump card to boost the dismal labour market: Bring more women back into the workforce.

His policy of “womenomics” in 2013 includes encouraging workplaces to be more accommodating so that mothers will be more willing to rejoin the workforce, and fixing day-care shortages.

To a certain extent, he’s succeeding. His policies have managed to add more than 1.5 million Japanese women to the workforce, while the female labour participation rate rose from 46.2 per cent in 2012 to about 50 per cent in 2017.

READ: The rise of woman economics in Japan is turning its ageing society around

“Right now, that participation rate is even higher than in the US. So we’re seeing some progress,” said Xia. But is it enough?

Tomoe Uchiyama, 37, quit her job after her son was born seven years ago. Like many of her peers who gave up their careers, she’s thinking about working again.

But she’s not optimistic about climbing the corporate ladder, given the strong gender bias in the Japanese workplace.

A man who is obviously not good at his job still gets a higher rank than a woman who’s clearly more capable.

"Male bosses tend to assign women to assistant jobs,” noted Uchiyama.

Japan remains very much a male-dominated society where women stay on the margins of business and politics. Said Xia, “There is huge social stigma about women who work too much, women who make too much money, women who don’t have children or don’t have time to take care of their children.”

Robots, on the other hand, are well-received in the workforce.

Unlike in many other economies, where they are seen as a threat to livelihoods, in Japan they are seen as a solution to the labour shortage. The government plans to quadruple the size of the robotics industry by encouraging automation in everything from rubber factories to elder-care.

Employees’ affection for robots extends to giving them nicknames – and even a farewell party in tribute to the machines when a factory shuts down. “Robots are usually considered your friends, not enemies,” said Komine.

“This is also why robots are very well developed in Japan,” he added. But even then, the revolution has not been able to progress fast enough to compensate for the rapidly declining workforce.

READ: It's cats and T-rex versus humanoids, as robots take over jobs in Japan

THE TOWN WITH A BABY BOOM

But one city has so far managed to buck the demographic trend in the rest of Japan.

Between 2010 and 2014, Nagareyama’s population grew by 1.16 per cent, while the country’s population growth averaged negative 0.7 per cent.

As the city’s mayor, Yoshiharu Izaki’s first strategy was to provide an innovative solution to young families’ childcare needs, by setting up a nursery transit service near the main train station.

Parents can safely drop off their kids in the morning, and the transit service will bring the children to their respective schools – leaving the parents free to head to work directly from the train station.

With the proper support, Izaki feels that women would be more open to the idea of having more children. “That was probably the first implementation of such a service in the Tokyo Metropolitan area, so many people were astonished,” he added.

Secondly, to help women continue with their careers after having children, Izaki brought the work – usually done in Tokyo – to Nagareyama city, turning it into a new satellite town.

This cuts down on commute time to Tokyo, giving parents more time to attend to their children’s needs.

To get the companies on board the idea, he provided them office space at low cost. The take-up was good and “many companies contacted us (to set up satellite offices)”, he said.

So far, this has benefitted more than 100 residents.

It remains to be seen, however, if one success story can be scaled up across the rest of Japan, whose demographic woes look set to continue for the foreseeable future.

Xia believes it may take the country another two decades to figure out how to generate productivity growth without population growth.

“I think it’s possible with a bit more changes in attitudes in Japan – with a more flexible labour practice, with a bit more gender equality, things might start changing in next 10 or 20 years,” she added.

Watch the Insight episode here.