Commentary: Cashing in on Coldplay kiss cam memes is risky business

The Coldplay concert incident highlights the dilemma of meme marketing: immense engagement potential, weighed against ethical and reputational risks, says SUSS’ Wang Yue.

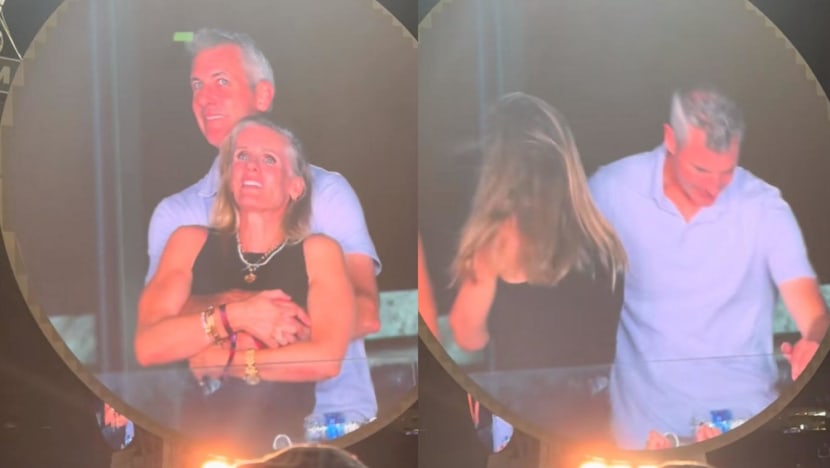

The two were seen cuddling when they were caught in the crowd cam at a Coldplay concert, in a video that then went viral. (Photo: TikTok/instaagraace)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: When a kiss cam clip at a Coldplay concert showed two tech executives in a seemingly compromising moment, it quickly amassed millions of views on TikTok and triggered a meme frenzy online.

Brands and organisations were quick to jump in. IKEA Singapore posted cuddly toys with an “HR approved” caption, while the Ministry of Defence referenced the incident in its National Day promotions.

But what some might see as savvy and real-time marketing also had its detractors. Was this clever cultural commentary, or exploiting a personal crisis for clicks?

THE BUSINESS OF GOING VIRAL

Memes have become a marketing tool for brands to tap into humour, relatability and shared cultural moments. It includes using established meme formats, jumping on online trends, or crafting shareable content that rides on viral moments.

The appeal is undeniable. According to news reports, ads containing memes saw 30 per cent engagement rates on Facebook and Instagram, as opposed to the 1 to 15 per cent engagement rate of influencer posts or branded content.

This trend reflects what media theorist Neil Postman warned about in his book, Amusing Ourselves To Death – where entertainment becomes the filter through which all events are processed.

This is especially true in digital spaces where social media algorithms reward engagement above all else, turning serious or private moments into content fodder. The trend is especially pronounced among users aged 13 to 36, with 75 per cent actively sharing memes.

WHEN MEME MARKETING WORKS

Some brands have managed to strike the right tone. US fast food chain Wendy’s “roast” campaigns, where it playfully calls out competitors, earned strong brand recognition by staying bold yet non-exploitative.

In Singapore, the “We let our Gen Z intern write the marketing script” trend resonated widely. It charmed viewers with older executives awkwardly delivering Gen Z slang – a format that worked because it embraced self-deprecating humour, humanised institutions and playfully acknowledged generational gaps.

Duolingo is another example of meme marketing done right. The language learning app has built a massive following on social media by employing self-deprecating humour, often leaning into memes about its “threatening” owl mascot that guilt-trips users for skipping lessons.

This playful and consistent persona has resonated with audiences, generating millions of interactions and growing its follower base to over 16 million users on TikTok.

WHY SOME CAMPAIGNS BACKFIRE

The success of meme marketing often hinges on brand alignment and the direction of humour. Campaigns that are congruous with a brand’s voice and identity tend to resonate more naturally, while forced or opportunistic attempts often fall flat.

For instance, Bumble’s 2024 “celibacy is not the answer” ad campaign, which included messages like “Thou shalt not give up on dating and become a nun,” was widely criticised for its judgemental tone when the dating app’s mission is to empower women.

Similarly, Pepsi’s ad in 2017, which depicted Kendall Jenner handing a can of Pepsi to a police officer at a protest, was criticised for trivialising social justice movements. When brands force connections to trending topics that don’t align with their identity, the results can be jarring.

The direction of humour also plays a critical role. “Upward” humour, aimed at competitors and “inward” humour, which is often self-deprecating and reflective, are generally well-received.

Wendy’s, for instance, uses upward humour to take jabs at rivals like McDonald’s, while budget airline Ryanair embraces inward humour by poking fun at its own service limitations.

Duolingo’s mascot-driven content also succeeds by tapping into shared language learning struggles, using relatable and self-aware humour that stays true to its brand ethos.

In contrast, campaigns fail when they rely on “downward” humour, which target vulnerable individuals. In 2014, DiGiorno's received backlash for using the hashtag #WhyIStayed to promote its frozen pizza, because the hashtag was for victims of domestic abuse to share their stories.

THE HUMAN COST BEHIND THE HUMOUR

Behind every meme are real people whose lives may be permanently altered. Those who experienced viral fame report lasting psychological trauma, including depression, social isolation, and loss of control over their personal narrative.

When brands participate in online trends, they risk legitimising the exploitation of others’ suffering. Over time, this contributes to desensitisation, where audiences become numb to the humans behind the jokes. The voyeuristic pleasure audiences derive from witnessing people’s shame reflects a deeper societal dysfunction where dignity is sacrificed for entertainment.

The Coldplay incident highlights the dilemma of meme marketing: immense engagement potential, weighed against ethical and reputational risks.

As digital audiences become more discerning, the brands that endure may be those that choose empathy over expediency. Sometimes, the most powerful message a brand can send is silence – recognising that not every trend is worth joining, and not every moment is a marketing opportunity.

Associate Professor Wang Yue is Head, Doctor of Business Administration Programme at the Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS).