Commentary: Singapore is going from cybersecurity to cybermaturity

As the lines between cybercrime and cyberthreats to national security blur, Singapore must be resilient, not reactive, says Dr Shashi Jayakumar.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Seven years ago, Singaporeans were shocked when a cyberattack resulted in the theft of personal data belonging to about 1.5 million SingHealth patients, including then Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong.

Yet, 2018 seems almost like a different age when it comes to cyberthreats.

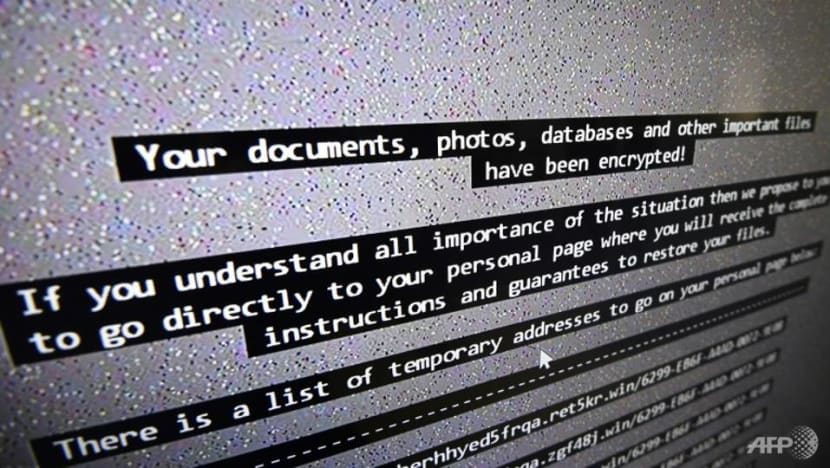

Last June, a ransomware attack on a service provider to the United Kingdom’s National Health Service disrupted operations in some hospitals, resulting in thousands of postponed surgeries and appointments. The hackers published almost 400GB of patient data on the dark web subsequently.

In February the same year, a ransomware attack in the United States compromised the data of about 190 million people and disrupted insurance processing that left patients the choice of delaying treatment if they could not pay out of pocket.

Halfway through 2025, there is no end in sight for the proliferation of this type of attack. A wave of attacks against prominent British retailers began in late April, with Marks & Spencer losing £1 billion (US$1.35 billion) in market value and another £300 million in lost profit expected.

Singapore is not immune: In April, cybercriminals struck local printing vendor Toppan Next Tech with ransomware, extracting customer information from DBS and the Bank of China, Singapore.

In the 10 years since Singapore’s Cyber Security Agency (CSA) was set up in April 2015, technology has evolved considerably, and with it has come an expansion of the threat surface.

Enterprises are increasingly moving to the cloud, where attackers now exploit weak identity and access management. Malicious actors have also taken to scams, fuelled by AI-generated content and deepfakes. Some target software supply chains or phish employees; others engage in hacktivism.

By sheer scale and scope, the lines between cybercrime and cyberthreats to national security have blurred.

NOT JUST REACTING

Singapore has not confined itself to reacting to an evolving threat environment.

It has shored up defences and increased awareness, within government and the private sector, through the creation of Singapore’s first Cybersecurity Strategy, the Cybersecurity Act and the Safe Cyberspace Masterplan. These ensure that organisations, particularly in the private sector, have the incentives and tools to implement cybersecurity measures and manage risks before any attacks occur.

Amid the increasing use of AI in cyberattacks, CSA launched in 2024 a comprehensive framework for organisations to manage cybersecurity risks throughout the AI system lifecycle. Its SG Cyber Safe programme offers resources such as toolkits and certification schemes like Cyber Trust marks to guide businesses in implementing cybersecurity measures.

Cyber diplomacy is also a key aspect, since malicious cyber activity and cybercrime knows no borders. Protecting the digital sovereignty of our country is just as important as safeguarding physical boundaries.

Singapore recognises that having a seat at the table to discuss on the dos and don’ts of state cyber activity, is critical for a small state.

When, in 2018, the United Nations Group of Government Experts (GGE) was undermined by disagreements between rival blocs, Singapore led ASEAN states to adopt the GGE’s voluntary norms of state behaviour in cyberspace. This took place during the Singapore International Cyber Week, which has itself become the key node for regional cyber discussions.

Singapore’s Ambassador to the United Nations, Burhan Gafoor, has garnered praise for his chairing of the UN’s Open-Ended Working Group on cybersecurity and information technology.

Singapore has also been a responsible stakeholder when it comes to cyber capacity building, establishing the ASEAN-Singapore Cybersecurity Centre of Excellence in 2019.

REALISTIC APPRAISAL OF THE ROAD AHEAD

In considering strategies Singapore can pursue, we should not be under any illusions about what can be done.

Some cyber practitioners have pushed for “attributing” cyberattacks, believing that calling out malicious conduct may prevent recurrences. For example, US lawmakers have blamed the Salt Typhoon attacks on US telecommunications infrastructure on Chinese groups.

While large states with well-resourced cyber offensive capabilities may take this view, Singapore’s position is somewhat different.

Observers would have noticed that there was no official attribution of the actor behind the cyberattacks against the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 2014, nor on SingHealth in 2018. In the latter case, it was made known that a state-backed advanced persistent threat was most likely responsible, but this is as far as the authorities went.

This is a space where the threat actors can cover their tracks through technical means, and even our close partners may probe our cyber defences or attempt to exfiltrate valuable information (especially if they feel they can get away with it without being caught).

In any case, a small state cannot afford to take the aggressive posture that others do, threatening retaliatory measures in response to every incident.

One major challenge is also in identifying and grooming the next generation of cyber defenders, when there is already currently a shortage of cybersecurity professionals in Singapore as is the case globally.

FROM SECURITY TO RESILIENCE

What more can be done?

Cybermaturity requires a mindset shift that recognises cybersecurity as a critical national and personal priority.

With CSA as the overall guide, more agencies will need, increasingly, to have skin in the game when it comes to covering digital threats. This process has already started.

When one falls victim to online scams or ransomware, one generally thinks to call the police, not the CSA. Under the Online Criminal Harms Act (OCHA) that came into effect last year, the Ministry of Home Affairs has the powers to deal with online content which facilitate malicious cyber activities. Technological solutions to counter the malicious use of deepfakes are also something that the SPF is working on, with the Home Team Science and Technology Agency.

Beyond policies and frameworks, real resilience requires deeper public investment: a cultural change, greater individual responsibility and baseline awareness.

CSA surveys consistently show a troubling gap: There is widespread acknowledgement of the importance of cybersecurity, but considerably fewer believe they are personally at risk. Awareness is also low in key areas such as Internet of Things (IoT) security, even as more invest in smart homes.

Silos make us vulnerable to threat actors who are using new tools with increasing sophistication and devolution. For the next leg of our cyber journey, it’s worth bearing in mind how CSA CEO David Koh sees it: We need to “assume breach”. This principle encourages not simply vigilance, but the ability to ensure continuity in a compromised environment.

This is the digital future we will have to live with – one brimming with promise, and also peril.

Dr Shashi Jayakumar is Executive Director of SJK Geostrategic Advisory, a security and geopolitical risk consultancy firm.