The Big Read: Undervalued, underpaid, disrespected – for some, a decent day's work just isn't treated the same by society

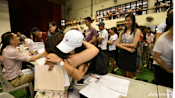

Despite various national efforts to improve employment prospects for non-university students, many Singaporeans still have low regard for those in technical and community care jobs. (Image: TODAY/Anam Musta'ein)

- Singaporeans working in technical, service and community care roles say that it takes months, if not years, to sharpen their skill sets and obtain the necessary certificates to perform the work they do

- But despite the fact that their jobs can be laborious and involve a certain level of skill and risk, many people perceive such jobs to require little training and intelligence

- This is not surprising given the high premium Singapore places on academic pursuit, say experts

- This was also highlighted last month by Deputy Prime Minister Lawrence Wong, who flagged his worries over a growing divergence in salaries among workers with different educational qualifications

- While this is a complex problem, the experts stressed the urgency of increasing the wages of technical and vocational jobs, as Singaporeans grapple with persistent inflation

SINGAPORE: At work, rope access technician Muhammad Safiuddin Abdul Rahman likens himself to Spiderman, the superhero with spider-like abilities, as he often dangles from high-rise buildings by just a rope.

The 29-year-old, who has been in the job for a year, said his work involves various tasks including maintenance work, inspections and cleaning. His workplaces range from deep waters to the top of buildings.

“Every day I risk my life at work,” said Mr Safiuddin, who spent five days on an Industrial Rope Access Training course before he was certified. “The job may look easy but it’s not. When you’re in the air, you need to think and solve any problems fast.”

Mr Safiuddin, who earns between S$150 and S$250 a day and an average of about S$4,000 a month, thinks his wages are adequate.

Monetary considerations aside, he has, however, encountered people who look down on his job.

“See, if you don’t study hard, you’ll end up like him,” a mother once told her children within Mr Safiuddin's earshot while he was washing the exterior of a mall at a low height.

Like Mr Safiuddin, licensed plumber Gary Tan, 37, also has had his fair share of unfavourable comments.

Mr Tan, who took two years to learn plumbing, oversees water tank cleaning as well as sanitary work for town councils and public schools as part of his job.

The former safety officer at a construction firm said he became interested in plumbing and sanitary works when he joined his current company in 2015, and decided to take a plumbing course. He subsequently obtained a licence in 2017.

“I feel our trade is quite similar to lift technicians where special skills set and certificates are needed to perform work. But the salary might not be as high as those at the executive levels (despite the fact) that our work involves high risk such as working at height and inside a confined space,” said Mr Tan, who earns around S$5,000 a month.

A licensed plumber typically earns more than a regular plumber, whose average salary is about S$3,000.

Still, when Mr Tan tells his friends about his job, their first reaction was that “they can always call me up when their toilet bowl is choked”.

“This is mainly because many people may think a plumber only fixes toilet bowls, taps and stuff,” Mr Tan said.

Mr Ziyad Ahmad Bagharib, 29, also had to deal with negative reactions from family and friends when he worked as a carpenter for two years after graduating from Yale-NUS College in 2018.

Referring to the initial resistance from his parents, he said: “They were just concerned that carpentry is a manual job that can be kind of dangerous. The pay is also not high. But (it was) the point in my life where I can still experiment so I just went for it anyway.”

As a carpentry apprentice at renovation firm Reno Scout, Mr Ziyad earned a gross salary of S$1,500 a month for his first six months as an apprentice before his pay was raised to about S$2,000.

He told TODAY that he would have continued pursuing his interest in carpentry had he not joined his family business as a sales manager last year.

Mr Safiuddin, Mr Tan and Mr Ziyad are among several Singaporeans working in technical, service and community care roles who were interviewed by TODAY, following a speech by Deputy Prime Minister Lawrence Wong last month where he flagged his worries about a divergence in salaries between workers of different educational qualifications.

The median starting salary for a university graduate is now almost twice that of an ITE graduate, said Mr Wong, who also noted that this earnings gap increases over the graduates’ lifetime.

Mr Wong also spoke about Singapore society's preference for intellectual “head” work, while not according sufficient value to "hands-on" technical jobs or "heart" work such as services and community care roles.

The workers interviewed by TODAY said that it takes months, if not years, to sharpen their skill sets and collect the necessary certificates to perform the work they do.

But despite the fact that their jobs can be laborious and involve a certain level of skill and risk, such as working at height or handling dangerous equipment, many Singaporeans have little respect for such jobs — perceiving them as needing little training and intelligence, compared with professions that require university degrees.

This is not surprising given the high premium that Singapore has long placed on academic pursuits, said experts.

Concerns about the widening wage gap between workers with different educational qualifications in Singapore have long been flagged by various quarters, including the Government.

In 2014, the Ministry of Education (MOE) formed the Applied Study in Polytechnics and Institute of Technical Education Review committee to study different apprenticeship and vocational systems around the world, as well as come up with recommendations to improve the job prospects and academic progression of polytechnic and Institute of Technical Education (ITE) graduates.

Since then, the ministry has launched programmes that integrate work and study — such as place-and-train programmes that are similar to the apprenticeship models in Switzerland and Germany — to provide more options for both polytechnic and ITE graduates to upgrade their skills.

The model has since been expanded under the SkillsFuture Work Study Programmes.

Despite various national efforts to improve employment prospects for non-university students, many Singaporeans still have low regard for those in technical and community care jobs. This, in turn, has resulted in society undervaluing such jobs, especially in monetary terms.

Experts interviewed said there is a dire need to plug the wage gap but acknowledged that it may not be easy to do so due to factors such as society’s mindset and employers’ buy-in.

“Ultimately, if money is always something that is overly emphasised in our society, people will always be valued by the amount of monetary value that they can generate," said veteran human resources practitioner Adrian Tan.

"DOES NOT REQUIRE MUCH THINKING" AND OTHER MISPERCEPTIONS

Singaporeans’ long-running obsession with the paper chase has often led to a misconception that those in technical, service and community care roles have less brain power and do not have a bright future.

Carpentry, for one, is a trade that is not very highly regarded in Singapore, mainly because the work of carpenters is often overlooked, said Mr Ziyad, who has a degree in anthropology.

“Before I joined the industry, I never gave a second thought about the people who built the cabinets in my (public housing) flat … it was like invisible labour,” he said.

Mr Ziyad said that while it may not be difficult to learn the basics of carpentry — he started taking on projects independently six months into his apprenticeship — it takes a lot of time and commitment to perfect the craft.

“The deeper I got into the industry, I realised that the best carpenters are all-rounded tradespeople. They know a little bit about electrical wiring, a little bit about plumbing and a little bit about aircon piping,” he said, adding that there is more to the trade than people think.

That is why in other countries such as Australia, New Zealand and Canada, carpenters are seen as professionals “that the society knows it needs”, Mr Ziyad pointed out.

He cited the example of Mr Scott Brown, a skilled carpenter in New Zealand whom he follows on YouTube.

Carpenters like Mr Brown are highly regarded in their community and are often accorded due recognition by their clients. They are also given a proper place to rest at job sites, said Mr Ziyad.

“People there are obviously aware of how valuable skilled craftsmen are in their society and they also value the fact that if these people are not around, no one is going to build their homes,” he added.

Another undervalued role is that of a community care worker, with friends of 28-year-old Ms Shai describing her job, which requires caring for seniors at an eldercare centre, as “boring” and “does not require much thinking”.

Ms Shai, who graduated with a degree in social work from the Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS), brings home about S$3,000 a month.

Even though many of her peers have out-earned her, she still stayed on in the job as she has built a rapport with most of the seniors under her care, said Ms Shai, who declined to give her full name.

“I would be lying if I say I don’t feel jealous (of higher-earning peers). But my work brings me great joy which is why I’ve stayed on for this long, ” said Ms Shai, who has been in her current role for the past three years.

Also finding much satisfaction in his job is Mr Muhammad Naz Farihin Muhammad Farhan.

The 25-year-old, who holds a Higher Nitec certificate in retail merchandising, worked as a driver with public transport operator SMRT Buses for two years before switching to the private bus industry to become an operational support officer.

In his current role at bus charter company A&S Transit, he oversees and coordinates its fleet’s training, maintenance and inspection.

The self-proclaimed bus enthusiast said: “Some may actually be surprised that being a bus captain in the field actually leads to progression far beyond driving."

He said he used to earn between S$2,800 and S$3,100 as a public bus driver. He is now earning about 30 per cent more.

In recent years, public transport companies have increased the salaries of bus drivers in a bid to attract more people to the industry.

For example, SBS Transit stated on its website that its entry-level bus captains can get an all-in gross salary of up to S$4,000 a month, with a sign-on bonus of S$6,000 for locals.

HAS THE PAY GAP WIDENED?

In the past five years, the starting salary of ITE graduates in full-time employment had increased by about 10 per cent, said MOE in response to media queries.

This was lower than the starting salary of graduates from polytechnics and autonomous universities, which had risen by about 15 per cent.

MOE said that the median salary of ITE graduates had increased by about 40 per cent in the last decade, "a higher percentage increase than that for polytechnic and autonomy university graduates".

Based on publicly available data, SUSS economist Walter Theseira said the wage gap between workers of different educational qualifications who had served National Service has remained largely similar or narrowed slightly throughout the last decade, in terms of what polytechnic and ITE graduates earn as a proportion of what university graduates get.

Over the past 10 years, polytechnic graduates have been earning about 70 per cent of what university graduates are getting while ITE graduates currently earn slightly above 60 per cent of what university graduates get, up from below 60 per cent a decade ago.

However, in absolute terms, the size of the gap has become larger: For example, polytechnic graduates earned S$850 less than university graduates in 2008, but S$1,000 less in 2018.

“So just keeping to the same proportional difference results in a larger absolute gap as time goes by and overall wages go up,” said Associate Professor Theseira.

He also noted that the wage gap between people of different educational qualifications in Singapore is a topic that is not well understood.

For instance, a critical question is not just earnings at graduation, but earnings over the course of one's career, as Mr Wong noted in his speech.

Assoc Prof Theseira said there is no publicly available evidence on this in Singapore, whereas in many other countries, studies have been undertaken to understand the lifetime earnings gap between workers with different educational qualifications.

In a recent commentary published in TODAY, Assoc Prof Terence Ho from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy noted that disparities in wages across occupations are also larger in Singapore compared with other countries.

For instance, the average monthly earnings of professionals in Singapore were about 2.9 times those of service and sales staff in 2020, whereas this ratio was 2.4 in Thailand, 2.3 in the United Kingdom and 2.0 in Switzerland.

While occupational wage disparities may be greater in a city-state compared with larger countries, Assoc Prof Ho said one contributor to this disparity is the culture in Asian societies, which are often said to value cognitive work over manual or craft labour.

In East Asia, some point to the lingering influence of Confucianism, in which scholar-officials were held in great esteem, and national examinations provided a reliable pathway for those from humbler backgrounds to move up in life, he said.

WHY THE GAP NEEDS TO BE NARROWED

In any society, the widening of wage gaps may cause further social divides, especially when it is grappling with stubborn inflationary pressures that the whole world is now facing, said the experts interviewed.

HR expert Adrian Choo, founder of career consulting company Career Agility International, said: “In some foreign countries, social discontent will be rife and it might be the starting point for mischievous politicians to begin sowing seeds of discord, which would be bad.”

Assoc Prof Theseira said that gap in lifetime earnings between people of different educational levels contributes to income inequality, as well as social stratification and lack of social mobility.

“Fundamentally, there are real skill and market value differences between educational tracks that do result in differences in earning outcomes. The question really is how large these differences should be, and whether people consider the existing differences fair," he said.

“Increasingly people don't consider the differences fair, especially since many jobs that require less education do involve considerable effort and commitment."

While society still prefers paper qualifications over practical skills, unionist K Thanaletchimi cautioned against pursuing “academic qualifications that may not be practicable and applicable from the industry perspectives and context”.

“This may indeed lead to perpetual high reliance on foreign talents as our local workers have skill mismatch or job mismatch, and that training opportunities driven by industry in collaboration with education institutes become limited and less valued,” said Ms Thanaletchimi, the president of the Healthcare Services Employees’ Union who is also a former Nominated Member of Parliament (NMP).

Assoc Prof Theseira added that with higher education opportunities in Singapore becoming increasingly accessible, the educational path which one takes tends to be a matter of choice, instead of being dictated by the amount of resources which one has.

“We do not want to incentivise people who are poorly suited to academic tracks to pursue degrees, especially if these actually offer little in the way of practical skills or training for many jobs," said Assoc Prof Theseira, who is also a former NMP.

“Yet many people feel that any degree is worthwhile because of the perceptions that better jobs are 'gatekept' by arbitrary degree requirements, which is often the case."

He added: "Ultimately, if we really believe that Singaporeans deserve to be able to earn a good living no matter what education they underwent, as long as they work hard and keep upgrading themselves, then our career prospects and lifetime earnings also have to reflect that."

TAKING A LEAF FROM EUROPEAN SOCIETIES

While Singapore has its fair share of vocational training programmes, it still has some way to go compared to the ones offered by several European countries.

Apprenticeship programmes there are widespread and rest on the premise that it is better to start young when training people for careers in advanced manufacturing.

In some European countries, students as young as 12 work with companies to get hands-on training while attending vocational school several days per week.

After graduation, these workers can apply for positions with the company that trains them or with other companies within the same industry. The companies typically foot most of the bill.

In Germany, companies fund 75 per cent of training, while state and federal governments pick up the rest of the tab.

The model stands in sharp contrast with the approach here: Apart from the Singapore Institute of Technology which uses the applied learning model — where students go on job stints lasting six to 12 months — institutes of higher learning here provide internships that are usually much shorter and less structured.

Related:

Assoc Prof Theseira said that while the idea of the vocational training structure in other countries is not new, the structure of the market for such vocational work is fundamentally different among various economies.

This reflects, among other things, differences in social value placed on skills.

As a country, Singapore has to review whether there is a relative lack of on-the-job training and apprenticeship in technical trades and the cause of it, he said.

Assoc Prof Irene Ng from the National University of Singapore's Department of Social Work said the key to shifting to an apprenticeship-based model of training is buy-in from employers.

“We need enough employers to sign on to take apprentices, commit them to train them for a career, and to also pay them higher wages than currently,” she said.

A COMPLEX PROBLEM BUT SOME THINGS NEED TO BE DONE — URGENTLY

Even though Singapore has one of the world’s best vocational training institutes that are much admired by many overseas, the perception of ITE graduates has not changed much over the years, again a reflection of society’s bias against “hands-on work”, said the experts interviewed.

In its response to media queries, MOE said it recognises that starting salary growth for ITE graduates has moderated in more recent years and it will continue to strengthen their career prospects.

The new three-year ITE curricular structure, which leads directly to a Higher Nitec certification, "will equip graduates with deeper industry-relevant skills for employment as well as providing a stronger foundation for further education and skills upgrading over the course of their careers".

ITE students can also upgrade themselves through ITE’s technical diplomas and work-study diplomas. The median starting salaries for graduates of these two diplomas in full-time permanent employment are comparable to that of polytechnic diploma graduates, said MOE.

Currently, more than seven in 10 Nitec graduates progress to Higher Nitec or pursue other publicly-funded upgrading pathways over the course of their careers, such as polytechnic diplomas or ITE’s Work-Study Diplomas. Some of them do so after having worked for a few years, MOE added.

Mr Choo, the HR expert, said that the constant push to increase the employability of ITE graduates can help produce more “career-smart” individuals who are more entrepreneurial and street-savvy.

"During COVID, the Government gave out grants to companies hiring fresh graduates to make them more ‘affordable’ during harsh times," he said. “Perhaps this could be done for ITE graduates as well, so as to make them more competitive compared to their cheaper foreign counterparts."

Assoc Prof Ng noted that different pathways have been set up through traineeships, internships, on-the-job training partnerships, and work study programmes.

However, several questions still need to be addressed. These include: How many employers are on board and committed to these initiatives? What proportion of ITE students are eligible to take up such programmes? What are the completion and placement rates? How much do ITE graduates earn after completing these programmes?

“Answers to these layers of questions can help us begin to understand and deal with the challenges of making these pathways for job placement and progression viable and effective,” she said.

Experts whom TODAY spoke to stressed the need to increase the wages of technical and vocational jobs, as Singaporeans grapple with persistent inflation.

Assoc Prof Theseira said: “I don't think there's a point to society talking about ‘upgrading’ technical and vocational job status until those jobs pay better.

“There are many bad jokes about lawyers, but at the end of the day almost any parent in Singapore would be happy to hear their child is dating a lawyer, because we know that profession is associated with financial security and success.”

He cited nurses and early childhood teachers as examples: They may feel that their jobs are socially useful and respected but many among them probably do not feel that this respect shows up fully in their pay.

“Talking about improving the status of vocational jobs without improving pay is really putting the cart before the horse; respect alone doesn't provide for your family," he said. “What you don't want is for vocational work to become a bit like being a classical musician or traditional artisan."

He added: "These are professions with quite a bit of social respect, but also ones that are notorious for financial insecurity, such that stereotypically one must either have independent financial support that pays the bills when the profession itself doesn’t, or be willing to make tremendous financial sacrifices to carry on the art.”

Ultimately, wages are market-driven: If employers can get away with keeping a larger part of the profits for top management and for shareholders, that's what they will do, he pointed out.

Agreeing, Mr Choo nevertheless said the onus is also on employees to see the benefit in going for skills upgrading and to move to a higher “value-creation role” in order to justify higher pay.

“For instance, nurses who want more salary could train to become operating theatre specialists, handling more complex tasks and procedures, but they must be willing to work harder and undergo very intensive training,” he said.

Employers whom TODAY spoke to said while they are keen to do their part to help raise the profile and salaries of vocational jobs, cost is the biggest obstacle.

Ms Chrysnie Lee, general manager of Kindly Construction and Services, said: “The support we get to do this is not a lot … It also has to depend on our profit. These days if you charge S$100 to unclog a choke already people will make noise."

Assoc Prof Ng noted that in her interviews with employers, some want to pay higher wages and send workers for training. However, unless this is legislated, it is hard to do so since their competitors are not doing it.

Thus, the pace of the implementation of the Progressive Wage Model — which was introduced by the Government to help increase the wages of workers through improving their skills and productivity — and its expansion to more sectors can be accelerated further to raise wages of ITE graduates, said Assoc Prof Ng.

Consumers must also be willing to pay more for services and products such as car repair, plumbing, hairdressing and house-cleaning services, she added.

She reiterated: “The need to pay lower-wage workers better has become urgent when inflation rates are high now. If middle-class individuals feel the pinch, this means low-income households are struggling.”

This story was originally published in TODAY.