How ube became the new matcha, and what it means for farmers when a crop goes viral

Consumers may jump on new food trends overnight, but farmers do not have that flexibility when they are faced with limited land, environmental regulations and the challenge of reshaping their land to grow a new crop, which can take months.

The explosion in ube's appeal mirrors the trajectory of matcha, which evolved from a niche ceremonial drink in Japan into a global viral ingredient. (Illustration: CNA/Nurjannah Suhaimi)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

Drawn to the nutty, creamy flavour of ube cream liqueur, Mr Dylan Yap and his business partners decided to bring it to Singapore in 2024, confident that consumers here would take to the taste of the purple root vegetable.

Ube is a purple yam native to the Philippines, traditionally used in Filipino desserts and known for its deep violet colour and subtly sweet, nutty flavour.

Mr Yap, co-founder of drinks distributor JD SIP, and his team began pitching the vibrant purple liqueur to cafes and bars, but many food and business owners were less receptive than Mr Yap had hoped.

"At the time (in 2024), no one even knew what ube was," he said. "When we spoke to bars about ube cream liqueur, they were sceptical about the product."

Barely two years later, Mr Yap said the demand for ube has grown exponentially, and the cream liqueur can now be found in 150 bars, restaurants and nightclubs here.

At a recent trade show, the distributor sold 400 bottles in just three days, something that was "entirely unexpected", Mr Yap added.

In the early days, JD SIP sold about 500 bottles of ube cream liqueur every quarter, but over the past eight months, sales have accelerated to roughly 500 bottles a month.

Pricing is set by retailers, with the leading stockist Cellarbration now selling the liqueur at about S$78 (US$60) a bottle.

Mr Yap no longer has to persuade bars and restaurants to try the ube cream liqueur. Instead, cafes and cocktail spots now approach him to ask how they can collaborate and incorporate it into their menus.

"Initially, we reached out to many bars, but now, bars are looking for us."

The shift, from widespread unfamiliarity to an almost feverish interest in a short span, has been striking, Mr Yap noted.

Indeed, the purple fever is global.

The lilac-coloured tuber's surge in popularity has spread far beyond the Philippines, finding expression in offerings as varied as ube Basque cheesecakes in the United Kingdom, ube lattes in Paris and ube doughnuts from a New York bakery in the United States with a 10,000-person waitlist.

Ube's ascent has not gone unnoticed by the food industry. In 2023, trend forecaster WGSN earmarked it as a top food trend, though its popularity has been building for years.

In 2024, California-based flavour house T Hasegawa USA named ube as the "Flavour of the Year" in its annual food-and-beverage trends report, highlighting the purple yam's growing global popularity and strong presence in desserts and drinks as key drivers of the trend.

This explosion in ube's appeal and ubiquity will sound familiar to many: It mirrors the trajectory of matcha, the finely powdered green tea, which evolved from a niche ceremonial drink in Japan into a global viral ingredient over the last five years.

Beyond matcha, other crops have followed comparable trajectories.

In the 2010s, quinoa went from a staple grain for people in the Andes of South America to a global "superfood" commanding high prices and broad adoption in health-food markets.

At around the same time, kale and chia seeds saw spikes in demand as wellness and plant-based eating trends took hold.

Amid the ube boom, a recent report in the New York Times noted that Filipino farmers are increasingly struggling to keep up with demand, constrained by labour-intensive cultivation and limited land. Erratic weather has also made rapid expansion difficult.

Dr Samer Elhajjar, senior lecturer in marketing at the National University of Singapore (NUS) Business School, said that consumers may switch habits overnight, but farmers do not have that flexibility.

"Crops and livestock are long-term commitments," he added, explaining that once a farmer plants crops or breeds livestock, he is locked in for months or years with money, land and labour already spent.

Exporters, importers and brand owners usually have the upper hand, because they control logistics, contracts with buyers, quality standards and how products are branded and sold, another academic said.

Associate Professor Guan Chong from the Singapore University of Social Sciences (SUSS) said: "Farmers lack real-time end-market price visibility. Agricultural production cycles (that are six months or longer) cannot respond to demand shocks in real-time.

"Scale-up requires investment inputs, processing equipment, and certification – only accessible to large-capitalised farms."

Assoc Prof Guan is also the director of the SUSS Academy, which is the continuing education and training arm of the SUSS.

CHASING TRENDY CROPS LADEN WITH RISKS

When a crop faces huge global demand, the instinctive reaction is to ramp up production. But for farmers who rely on other crops as their main source of income, switching to the flavour of the month is fraught with logistical difficulties.

Mr Jeremy Chua, who has been in the farming industry for 12 years, said: "Farming is not like urban farming in Singapore. In Southeast Asia, it's really a choice of what I know, and a question of 'Will this feed my family?'"

When there is a craze for a particular produce, farmers are often one or two steps behind the trend and therefore, are slower to benefit greatly from that crop.

Mr Chua, who is the chief technical officer at biotechnology firm Bio Ark Global, added: "There will be this wait-and-see approach and usually, by the time (the farmers) decide to pull the trigger, everybody decides to kind of pull the trigger at the same time."

Ultimately, the farmers often "don't see the price uplift that they are expecting".

Mr Chua also said that farmland is finite, and the increased environmental protections against deforestation for more arable land make farmers hesitant to switch to the viral crop of the moment.

For most farmers in Southeast Asia, their livelihoods rest on staple crops such as rice, coffee and corn. These commodities come with known seasons, established buyers and predictable outcomes, making them more reliable for farmers.

As such, switching to a different crop is not so much a pivot as a wager, one that requires reshaping the land and waiting months, or years, before any return appears.

Mr Chua said that some farmers can try growing different crops between seasons, but that, too, carries risk and time to prepare.

The same constraints apply to matcha, which is facing a supply shortage.

Despite soaring global demand, farmers say it is not as simple as planting more tea, because land is limited and pushing for volume risks compromising quality.

Mr Daiki Tanaka, founder and chief executive officer of D:matcha Kyoto, said that demand for matcha has increased exponentially in the last two years. His tea farm in Kyoto often has to turn down wholesale requests to ensure that quality is not compromised.

Mr Tanaka has been running the farm for close to 10 years and has four hectares of farmland in the Japanese prefecture to grow tea.

"There's always a limit," he said in an interview with CNA TODAY via video call from Kyoto. "Even as demand grows, our supply can only go so far."

Mr Tanaka said that in Kyoto's mountainous farming areas, large machinery simply cannot be used, making it impossible for farms such as his to scale up production to meet surging demand.

"We farmers have to be in the fields ourselves," he added.

Unlike in flatter regions, where industrial farms can span hundreds of hectares, matcha cultivation in Kyoto remains labour-intensive and constrained by terrain, Mr Tanaka explained.

"We do not chase the demand, and as we have always done, we prioritise quality."

Meeting demand is only one part of the equation. For matcha farmers, the opportunity cost of expansion weighs just as heavily.

Mr Iwan Ong, who runs Soenday, a Singapore-based tea retailer, and has worked with Japanese farmers for nearly a decade, said that scaling up is more complex than it seems.

Tea plants take time to mature and land cannot be repurposed quickly.

"Even if (the tea farmers) buy out the land from older farms, they need to revitalise the whole land and plant again, and that will take another five years," Mr Ong said, noting that Kyoto's tea-growing regions are already densely cultivated.

Even when demand surges, farmers face hard limits. "There's no way they can expand their farms like that."

Production cannot simply be increased without long-term risks, he added.

Interestingly, the thirst for matcha has prompted a small, positive shift on the farms in Kyoto. Mr Tanaka noted that the children of farmers who had left their rural hometowns are beginning to return.

"In the past, it was not common," Mr Tanaka said. "Now, being a tea farmer is becoming one of the options for their future careers."

A similar set of constraints is now emerging for ube producers, where rising global demand is colliding with limited land, long growing cycles and the realities of small-scale farming.

Mr Kalel Demetrio, a Filipino co-founder and co-creator of Ube Cream Liqueur, said that the global appetite for ube has translated into a very real shift on the ground in the Philippines.

When he first began sourcing the purple yam in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic, supply came from a small number of farmers growing ube largely for the domestic market.

Today, he said, demand has grown far beyond what any single farmer or even a small co-operative can comfortably meet.

Ube Cream Liqueur is part of a distillery called Destileria Barako that Mr Demetrio co-founded. Based in the Philippines, he often travels to Singapore on business.

The New York Times report found that ube exports from the Philippines have increased dramatically, reaching over 200 tonnes yearly, a fourfold increase in recent years. One tonne is equivalent to 1,000 kilograms.

However, annual ube production in the Philippines has slipped from more than 15,000 tonnes in 2021 to about 14,000 tonnes in the past two years, with most of that for local consumption, government data showed.

To keep up with demand, Mr Demetrio said that he has had to commission more growers and work with farmer cooperatives, expanding beyond his original suppliers. Even then, supply remains tight.

"It's not hard to grow, but the demand right now is booming, because ube is the next matcha."

The challenge, he said, is not price, because farmers have only asked for modest increases, but the volume of ube grown.

Mr Demetrio said that land is limited, growing cycles are long and ube is labour-intensive to harvest, often on sloped or hard-to-access terrain.

Ube generally takes six to 12 months to mature.

The pressure is also compounded by competition around the region.

As ube's popularity spreads, neighbouring countries such as China and Vietnam have begun planting their own purple yams, raising concerns among Filipino farmers that they will be undercut by producers with more land and mechanised farms.

NOT QUITE THE REAL THING

When demand for a crop surges faster than supply can respond, mislabelling, grade inflation, or substitution often emerge.

In the case of the global matcha boom, this has been reflected in the rise of counterfeit products and marketing terms that promise quality.

Regular matcha consumers would be familiar with seeing the term "ceremonial grade" to describe higher-priced matcha, implying the product is of a higher quality than usual.

However, "ceremonial grade isn't really a term from Japan," Mr Tanaka said. "It's a marketing buzzword created overseas."

Mr Tanaka said that traditionally, in Kyoto, matcha intended for tea ceremony or drinking comes from the spring harvest, though quality still varies depending on the cultivar and the farmer.

Spring-harvest matcha is prized for its sweetness and vibrant colour, while leaves picked in summer tend to be more bitter and are usually used for lower-grade or culinary applications.

Mr Tanaka said that what is now marketed internationally behind the vague label of "ceremonial grade" can refer to very different products — from traditionally produced matcha made from shaded spring-harvest tencha, to green tea powders that bypass key steps such as proper shading, tencha processing or stone grinding, yet are still marketed as ceremonial matcha.

Tencha is a type of tea leaf that is ground into a powder and then used for matcha.

Assoc Prof Guan from SUSS said that supply shortages often invite opportunistic behaviour such as mislabelling and other unethical behaviour.

When products are sold as "authentic" or special, people are willing to pay more for them, she noted. But once consumers start to doubt whether those claims are true, the higher prices quickly stop making sense, and demand can fall just as fast.

"With ube, substitutes inevitably start to appear," Mr Chua from Bio Ark Global said.

"Purple yams from places like Indonesia or Vietnam begin entering the market, even though they're not ube. That's part of how the food supply chain works once the demand surges."

Although many such root vegetables share a purple hue, true ube stands apart for its creamy texture and distinctive vanilla-like flavour, qualities that purple sweet potato, taro and other regional yams do not have.

Mr Chua added: "Most of the time, it isn't farmers who misrepresent the product. It's usually suppliers or wholesalers who see a trend and try to pass off a close substitute as the real thing."

On the deluge of matcha labelled "ceremonial grade", Mr Ong from tea retailer Soenday shared Mr Chua's sentiment that it is not driven by farmers but by sellers and retailers, since there is no official definition for the term.

Mr Ong said: "It's down to the customers to be able to discern and understand what they are consuming. To do their own due diligence on what is a good product."

Although Mr Tanaka was encouraged by the global appetite for matcha and the wider embrace of Japanese culture, he was more concerned about demand swings that could push prices down and leave farmers exposed to a volatile market.

"It's not just me – many farmers feel the same way," he said. "We're worried about how demand will fluctuate, especially as more matcha from China and other regions enters the market.

"That's why we're focusing on quality. Many farmers are choosing to invest in quality even as demand grows."

China has been significantly ramping up production of matcha in Tongren City, in the southwestern province of Guizhou, where it boasts the world's largest single-site matcha factory.

In 2024, Tongren exported 180 tonnes of matcha, and in the first half of 2025, exports reached 230 tonnes, up 42 per cent year-on-year.

In comparison, Japan produced 5,336 tonnes of tencha in 2024, the Japanese Tea Production Association stated.

However, an investigation by Japanese news outlet MBS News found that some Chinese producers avoid promoting the Chinese origin of their matcha and instead use Japanese-style branding and label their products as being “Uji matcha”, even though these were made in China.

Uji is a traditional matcha-growing region in Japan.

Viral demand can cause over-investment, misallocation of land and water, as well as price volatility.

Assoc Prof Guan said such shifts are typical of trend-driven markets. When a crop becomes popular, farmers can initially earn higher prices.

Then, as more producers in different countries start growing it, supply increases and prices usually fall, so those higher earnings do not last, she added.

Agreeing, Dr Elhajjar from the NUS Business School said that in the short run, consumers usually pay through higher prices or shortages. In the medium to long run, though, farmers often carry the bigger risk.

If farmers invest to meet demand and the trend fades, they are left with sunk costs and unsold supply.

"Farmers' exposure to risk rises faster than their ability to diversify," Assoc Prof Guan said, warning that such repeated cycles can push farmers into debt and weaken the food system.

Dr Elhajjar said that as volatile markets correct themselves and stabilise, it is not without casualties.

"Viral demand can cause over-investment, misallocation of land and water, as well as price volatility," he added.

"By the time the correction happens, damage may have already been done to farmers, ecosystems or small producers who can’t absorb shocks."

In the case of quinoa, demand began soaring in the 2010s, reaching a frenzy in 2013, with prices rising sharply and doubling in 2014.

Peru’s quinoa exports reflected that boom. From about US$31 million in 2012, export value jumped sixfold to roughly US$197 million just two years later.

Yet, this spike came at a cost. Soaring prices saw poorer households in the country unable to afford what was to them a household dietary staple.

Furthermore, when the market corrected in 2015 and prices plummeted, many farmers who had invested heavily in quinoa found themselves in a financial crisis.

In 2012, 1kg of quinoa cost US$3.15. In 2014, the price shot up to US$6.74 a kilogram. By 2017, however, the price had dropped dramatically to US$1.66 a kilogram.

Aside from bearing in mind this instructive lesson from the quinoa boom, tea farmers now also have to weigh some difficult trade-offs.

With limited land, matcha farmers must decide whether to convert fields now used for other teas, such as sencha or hojicha, which still have strong domestic demand from Japanese tea houses, or keep production as it is, Mr Ong from Soenday said.

"It's a serious business decision. For the farmers, they just have to compromise.

Mr Ong also said that farmers have to dedicate certain plots of their land as "innovation lots" to grow new products as a way to stay relevant.

For Mr Tanaka, his Kyoto farm has prioritised building a loyal customer base through direct sales. He believes that long-term relationships are more sustainable than scaling up production.

"Because our harvest is limited, we've chosen to focus on direct-to-consumer sales and building loyal customers," he said.

"That way, people understand where the matcha comes from and why it's different. It's more sustainable for us than chasing volume."

FAD OR FOREVER FAVOURITE?

For some people who grew up with these foods, watching them become global phenomena has been both affirming and disorienting.

For Ms Kate Orcena, a 32-year-old software engineer, ube was never an everyday ingredient in the past.

In her childhood days in the Philippines, ube appeared mostly in desserts such as ube halaya and halo-halo, which were made for special occasions.

Ube halaya is a thick, sweet purple yam jam. Halo-halo is a popular Filipino shaved-ice dessert layered with fruits, jellies and often ube or ice cream.

Seeing ube now so readily available overseas, especially in Singapore, has been a pleasant surprise.

"I like how much easier it is to find ube products now," she said, adding that the higher prices abroad are understandable, given the import duties and taxes.

In the Philippines, she noted, ube remains relatively affordable.

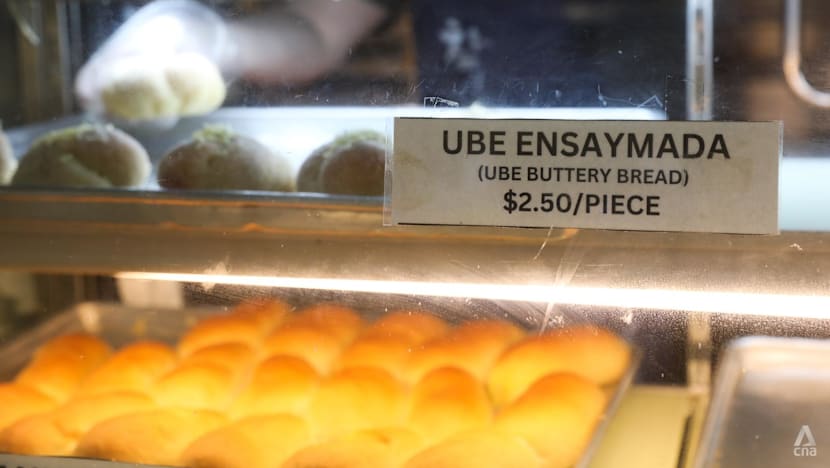

Ms Nikki Rosales, a 37-year-old, said that ube has always been everywhere in Manila, from jams to breads to ice cream.

A graphic designer based in Singapore, she is happy that more people now know about ube, but wonders whether global consumers have really developed a genuine taste for the root vegetable.

"I'm sceptical if people will like it for long or if they're just following what's unusual and new to them.

"I'm not sure how curious they are about how ube is made and where it came from."

For Japanese consumers, the dissonance runs deeper.

Singapore-based online content creator Nana, in her 30s and raised in Japan, said that matcha-flavoured sweets and drinks were common in her childhood, but traditional, high-quality matcha was not something most families prepared at home.

"In Japan, not many people practise the tea ceremony and traditionally, matcha is something enjoyed within a very structured ritual with specific etiquette." She runs the Instagram account @nana_japanfinds.

With farmers under mounting pressure, and cultural foods increasingly diluted by global demand, the question arises: What role, if any, should consumers play in slowing the cycle?

"Total consumer responsibility is unrealistic," Dr Elhajjar said.

"Most people respond to price, availability and social signals. That's human.

"But there is a case for greater awareness, especially around extremes such as panic-buying or trend-driven moral pressure."

Even small shifts, such as supporting diversified diets, valuing seasonal products, or being sceptical of hype, can reduce volatility, Dr Elhajjar added.

"The burden shouldn't sit only on consumers, but ignoring their role entirely also misses part of the picture."

Nana said: "It would be wonderful if the global popularity of matcha also helped people to learn more about the tea ceremony itself, which has been an important cultural tradition in Japan for a long time."