'Everyone feels scary': How catfishers are turning some singles off dating apps

The highly competitive nature of online dating has meant that more people are willing to fake their identities, with wider implications for dating norms, experts say.

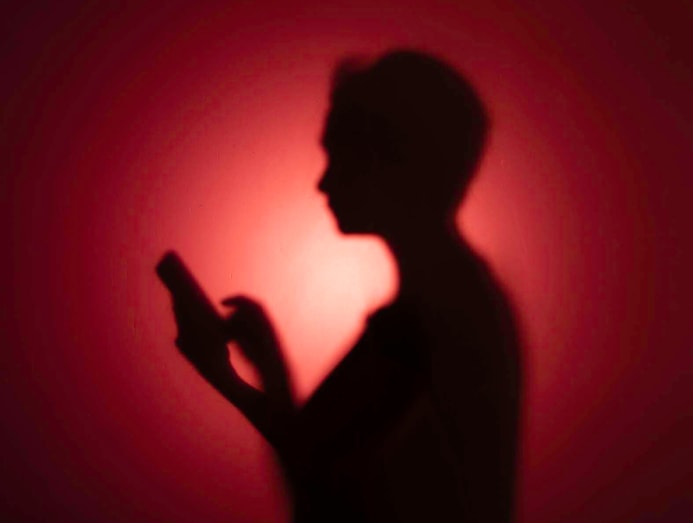

Despite verification tools in dating applications, catfishing remains the most common form of online harm faced by Singapore residents. (Illustration: CNA/Nurjannah Suhaimi)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

After a week of chatting online with someone she matched on dating application Bumble last year, Ms Xie Hui Xia, 29, felt optimistic about their first date.

When the man picked her up for dinner at 8.30pm, she noticed he looked a little different from his profile pictures, but she chalked it up to the poor lighting.

"The moment he stepped out of the car and into the light, I was completely shocked," she said. "This is definitely not the person I thought I'd been talking to."

Not only was he noticeably shorter and heavier than his pictures – he looked like an entirely different person.

Ms Xie felt so blindsided that she was too shocked to speak during their meal at a Japanese restaurant in Hillion Mall.

A friend, who was tracking her location as a safety backup, called after receiving a code word via text from Ms Xie and pretended to be in the hospital, providing a timely way out.

"It was honestly traumatising. I'd been on dating apps for about five years, so I never thought I'd be catfished," she said.

She swore off dating apps for at least six months but eventually returned after some encouragement from friends, though more wary than before.

Such fraudulent encounters are no longer rare in the world of online dating.

Catfishing, the act of assuming a false identity or significantly misrepresenting oneself by using fake or heavily edited photos and misleading details, has become a familiar risk and is now the most common type of online harm experienced in Singapore.

The Perceptions of Digitalisation Survey by the Ministry of Digital Development and Information found that 71 per cent of residents who had experienced any online harm had been catfished.

In comparison, 27 per cent reported receiving unwanted sexual messages and 16 per cent faced online harassment.

The survey, conducted from November 2024 to February 2025, polled 2,008 Singapore citizens and permanent residents aged 15 and above.

In 2024, the Netflix documentary Sweet Bobby brought the issue of catfishing into the spotlight – shocking viewers across the globe with the story of radio presenter Kirat Assi, the victim of an elaborate catfishing scheme which upended her life.

For nearly a decade, she was led to believe she was dating a cardiologist and that they were even engaged.

In reality, the man she believed she was speaking to was actually her own female cousin, who sustained the ruse by creating nearly 60 false identities and a web of lies over the years. She had never met the man in person.

Plausible explanations were offered for every gap, including claims that the man had damaged vocal cords – an excuse Assi accepted for the text-only replies and barely audible phone calls.

Assi's story, though extreme, put into sharp focus how catfishing can extend far beyond an awkward first meeting.

PATTERNS OF DECEPTION

Before the shock of realising someone isn't who they claim to be, interviewees who had been catfished told CNA TODAY that with hindsight, they have been able to identify red flags that something was amiss before their first in-person encounter.

Deleted chats, refusal to provide verification, and sudden shifts to other messaging platforms were recurring patterns of behaviour observed by those who later discovered they had been catfished.

Catfishers tend to shift to other messaging platforms after starting to chat with a match so that they can delete their profile on dating apps in case they get reported or so that victims don't continue scrutinising their fake profiles on the app.

Ms Xie, for instance, noticed that her Bumble match immediately deleted their chat on the dating app once the conversation shifted to Telegram at his insistence.

When she asked why, he claimed he had "too many chats" and didn't want to clutter his phone.

"It already felt a bit suspicious, so I don’t know why I fell for it, but I didn't think too much about it and continued chatting," said Ms Xie.

She wasn't alone in overlooking these red flags.

An undergraduate student, who wanted to be known only as Ms Zheng, realised she was being catfished about a week into messaging her Hinge match two years ago.

The catfisher would send photos of his activities throughout the day, a tactic typical of someone trying to maintain the illusion of a busy, authentic life.

The deception ended when a careless mistake left one photo uncropped, revealing it had been taken from the Instagram account of a Japanese model with 20,000 followers.

The 22-year-old confronted the culprit, only to find herself immediately blocked.

"He also said he only used email and text messaging, which feels really weird now that I think about it," said Ms Zheng, who is no longer on dating apps.

He also said he only used email and text messaging, which feels really weird now that I think about it.

Attempts to video call the man were often deflected with excuses, such as a broken camera or a poor internet connection.

For Ms Florence Chee, who works in the finance industry and is in her 30s, some of these early red flags marked the start of a catfishing experience that extended beyond emotional deception and into financial loss.

Hoping to settle down, Ms Chee turned to dating apps and connected with a man who called himself Aiden on OkCupid in early 2024.

Over the span of a week, they spoke on the phone for two hours every night, during which he earned her trust with detailed stories of his life – including his move to Singapore from Ipoh, Malaysia and his life here, where he claimed to live in a condominium near Redhill MRT station.

Eager to see him on camera, she would ask if they could do a video call, but he claimed his phone camera had been damaged.

Believing him, she asked for photos instead, unaware that the images he shared were not of him and had been taken from elsewhere online.

Convinced by his explanations, Ms Chee continued the relationship, believing she was talking to a genuine person.

"Looking back, I'm just an average-looking person. Why would someone who looked so good, and was so talented and tip-top, match with me?" she said.

During the next week, Aiden asked her to invest in a sustainability platform, claiming it was by invitation only and low-risk – framing the investment as a way for them to secure a future together.

"He promised me a lot of things. I believed his fairy tale about the future – having kids and pets together."

The truth emerged only when a bank officer alerted her to the scam after noticing unusual transfers. By then, she had lost over S$40,000 (US$31,153) to the catfisher.

Even while filing a police report, Ms Chee struggled to accept what had happened, holding onto the hope that Aiden was who he claimed to be.

The ordeal has since kept her off dating apps, leaving her wary of online connections and uneasy about meeting people virtually.

"Everyone feels scary, like they could be anyone," she said.

For Mr Marcus Toh, 24, the deception was subtler and involved heavily edited or outdated photos that presented an online image far removed from reality.

Mr Toh, a healthcare worker who has been using dating apps for about a year, said multiple matches looked markedly different when they met in person, such as appearing younger and of a different build.

He added that over time, such encounters have become less shocking to him, even if they remain disappointing. He described them as a reality that many users now quietly expect and accept.

"It makes me feel like I was deceived and my time was wasted," said Mr Toh. "But I've come to accept it as part of the dating app experience."

Some others such as Joseph, who declined to give his real name, discovered just how easily it can happen after being catfished not once, but twice.

About three years ago, having just ended a serious relationship, the 23-year-old decided to try dating again and agreed to go on a Hinge date.

It took him some time to find his match in an ice cream store in Tanjong Pagar – not because of the crowd, but because his match looked nothing like the profile picture.

"He lied about his build, but it wasn't even that he looked better in his pictures, he was basically a different person," he said.

He lied about his build, but it wasn't even that he looked better in his pictures, he was basically a different person.

Joseph felt it was too awkward to leave immediately, so they still spent roughly an hour talking, but the experience was enough to prompt him to take a two-week detox from dating apps.

"I felt so stupid and (I was) scammed. It made me much more wary about who I meet from dating apps."

He also encountered one of the red flags described by other interviewees: his Hinge match refused to provide social media details, insisting they meet first.

"I always ask to move to Instagram because there's more verification," he said, adding that he regretted making an exception in this case.

Despite being more cautious after his first experience, he found himself misled once again about a year later on another app.

His match sent a blurry photo earlier and arrived in a hoodie, but like Ms Xie, he chalked up the difference in appearance to the dim lighting.

The moment they were in a brighter setting, he realised his match was at least 20 years older.

Shaken, he deleted the app immediately.

THE PERFECT STORM FOR CATFISHING

Experts said a "perfect storm" has emerged in today's online dating landscape, where features of dating apps and societal pressures make catfishing easier and more prevalent.

Dr Kenneth Tan, an assistant professor in the School of Social Sciences at Singapore Management University (SMU), said dating apps have made it both easier and more compelling for people to catfish.

He explained that the anonymity of the internet lets people separate their online and offline identities, sometimes without ethical constraints.

Communication spread out over time also gives catfishers the opportunity to carefully craft how they present themselves, unlike in face-to-face interactions.

"Furthermore, verification can be difficult because of the lack of common social networks, unlike in offline dating. One's reputational cost is also minimised because people can engage in 'ghosting', or remake profiles," said Dr Tan.

"Ghosting" refers to the act of abruptly cutting off all communication with another individual without warning or explanation.

When it comes to the motivations behind catfishing, experts said that they can vary widely – ranging from financial gain to entertainment to societal pressures.

Ms Stella Ong, clinical counsellor at LightingWay Counselling and Therapy, said: "Some people are driven by insecurity and they create identities with qualities that they wish they had, or feel that they lack in real life."

For some victims such as Ms Xie, confronting their catfisher offered a way to make sense of the deception, regain a sense of control and seek closure.

Her catfisher had given personal insecurities as the reason for the deception – a motive that, while difficult for her to accept, aligns with what experts observe in the broader landscape of online dating.

Dr Tan noted that the gamified nature of dating apps, with their rapid swiping and constant comparisons, intensifies pressure to compete in the online dating "market", which can encourage catfishing.

"Loneliness, fear of being single, and the abundance of choice can also drive people to create false identities in search of companionship," he said.

Others may also catfish for the thrill or self-interest, with traits like narcissism or manipulativeness making them more likely to engage in such behaviour, while research has shown that some individuals may use it as a way to "come out" or explore their sexual identity.

Interviewees CNA TODAY spoke to described a sense of shame and self-blame after being deceived, highlighting how catfishing preys on a human desire for connection.

"I blamed myself many times, wondering why I believed him. I never expected to get financially scammed by a catfisher because I work in the finance industry," said Ms Chee.

Ms Ong, the clinical counsellor, observed that this self-blame can stem from a perceived lapse in judgment, which may be affected by factors such as the desire for connection or major life transitions.

"When we are in that vulnerable emotional space, we tend to focus on what we hope is true and can sometimes dismiss warning signs and red flags," she explained.

At a societal level, Dr Tan from SMU said catfishing can erode baseline trust in online interactions and make people more guarded, approaching connections with suspicion.

With online platforms now central to social life, romantic norms can shift from "connection first" to "proof first", making dating feel transactional and cautious.

"It could also raise concerns about surveillance and the balance between security and privacy," he said, adding that catfishing might have a far-reaching impact beyond just individual victims, but also overall trust and how people interact online.

PLATFORMS STEP UP SAFETY MEASURES

Ms Rachel Tee, head of trust and safety at dating app Coffee Meets Bagel, said fake profiles continue to make up the majority of reports received, and are a problem not just on dating apps but across other online platforms.

To curb its rising prevalence, in June last year, Coffee Meets Bagel rolled out Singpass-based identity verification for users in Singapore – making use of government records to tackle scams and hidden marriages.

Since its implementation, more than 80 per cent of profiles locally have been verified, and user complaints from Singapore have fallen by 50 per cent.

Although reactions to the verification method have been mixed, with some users raising privacy concerns, the app has reported an increase in Gen Z users, suggesting that safety features are a priority for younger daters in their 20s.

Beyond verification by Singpass, which is the national authentication and passcode system for e-services, Coffee Meets Bagel uses machine learning to spot fraud signals in real time and moderates opening messages, blocking suspicious content before a match is made.

Users reported for serious misconduct, including criminal threats, are permanently banned by the platform without necessarily confirming the reports with law enforcement. Coffee Meets Bagel explained that checking with the police could delay action, so the app errs on the side of caution.

The culprits are then monitored by tracking their devices and behavioural signals to prevent their re-entry to the platform using new identities.

Dating app giant Match Group, which owns and operates popular platforms such as Tinder, OkCupid and Hinge, said the firm has also stepped up efforts to tackle fake profiles.

In October 2025, Tinder introduced Face Check, a mandatory facial verification for all new users in the United States.

The feature uses a short video selfie to create a 3D scan, verifying profile photos and spotting duplicate accounts.

I've reported people before on dating apps, but I never know what has been done to the user. It would be good if we could receive follow-ups.

Early pilots in California, Australia and India showed it cut impersonation reports by 40 per cent.

Match Group told CNA TODAY it has plans to roll out the Face Check feature in Singapore soon, but did not elaborate.

For its part, dating appa Bumble, provides video chat features to help users confirm identities before meeting in person.

While dating platforms have stepped up efforts to curb fake profiles, some users told CNA TODAY that the measures do not always translate into a greater sense of safety.

Ms Zheng, 22, said that while she understands the challenge of weighing safety against privacy and ease of use, the lack of follow-up after reports can make users feel unsupported.

"I've reported people before on dating apps, but I never know what has been done to the user. It would be good if we could receive follow-ups," she said.

When it comes to keeping pace with catfishing, Dr Tan from SMU said technological fixes alone are unlikely to be enough.

Even with measures such as identity verification and chat moderation, he said that exploiters just need to find a single loophole to continue their deceptive conduct, resulting in prevention efforts often being outpaced by the persistence of online deception.

"We would probably also need to address psychological vulnerabilities like the loneliness epidemic, or build resilience through awareness of dark triad personality traits or attachment-related issues, but these changes take longer to implement," he said.

Looking back, Joseph urged others in similar situations to be kind to themselves, take time to process their emotions, and seek support without shame.

"My advice would be to be more diligent when you're on these apps, and to know that not everyone is going to have the same intentions as you."