‘Loneliness seems to hit the hardest’: The defectors who struggle with life outside North Korea

More than 34,000 North Korean defectors are known to have entered South Korea since the peninsula was divided more than seven decades ago.

North Korean defectors Han Ser Song (L), Heo Jin Hwa, and Nam Yeong Hwa (R).

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SEOUL: When Mr Han Ser Song fled the repressive regime of North Korea with his father in 2014, he faced a different set of problems altogether – the inability to hold down a job or perform simple tasks.

The pair landed in the high-tech South Korean capital of Seoul after a perilous journey from the hermit kingdom.

In those early days, Mr Han – then aged 22 – went for nearly 30 interviews for part-time jobs such as a convenience store cashier and milk deliveryman.

Nothing worked out.

More than 34,000 North Korean defectors like the Hans are known to have entered the South since the Korean peninsula was divided more than seven decades ago.

Their numbers dropped sharply during the COVID-19 pandemic when countries closed their borders. But as restrictions eased, the number of defectors last year – 196 – nearly tripled from the year before.

Seoul’s Unification Ministry said they included a considerable number of so-called “elite” defectors, including “diplomats, overseas residents and international students”.Many newcomers to South Korea struggle with simple tasks like taking the bus, paying their bills or buying groceries.

The most daunting challenge, however, is finding work to meet their basic needs.

Mr Han said he initially thought he was discriminated against due to his North Korean roots, but soon learned it was because his speech and service-oriented skills were not up to par.

“Looking back now, I realise that the people I interviewed with were mostly self-employed, so they have the freedom to hire part-time workers while earning money themselves. That's why they don't hire part-timers who aren't beneficial to them,” he told CNA.

AN ACADEMY JUST FOR DEFECTORS

These knowledge and experience gaps faced by North Koreans led another defector, Ms Nam Yeong Hwa, to run an academy just for them.

Ms Nam arrived in South Korea in 2003. She set up H Nuri Education Centre a decade later to train students in becoming certified accountants, then began taking in only North Koreans, who found it difficult to keep up with regular classes.

She said: “North Korean defectors often submit their resumes to various companies but give up because no matter how many resumes they submit, they can't get interviews or responses.

“As a result, there aren't many defectors who are employed and working. So I thought: ‘This must be what I need to do.’”

Defectors learned the Russian language back home and are not familiar with English, Ms Nam said. This makes learning how to use a computer keyboard difficult, and they end up repeating the same words frequently.

Variations in the Korean language following decades of separation compound the difficulties. They are often confused by “Konglish” – a combination of Korean and English that is commonly used in the South.

Such issues expose defectors to mockery and isolation even after they land a job.

“They often try to leave the company within three to six months,” Ms Nam noted.

“People might think their speech is a bit awkward, and when they ask questions, their colleagues often look at them like: ‘Why don't you even know that?’ It makes them feel like they can't fit in.”

Ms Heo Jin Hwa, a student at H Nuri Education Centre who defected from North Korea 12 years ago, said there was a “huge difference” between the reality of South Korea and what she imagined it to be.

“When North Koreans come here, we are adults, but we are like newborns,” she told CNA.

“If we can't communicate at all, we'll learn everything from the beginning. Lifestyle, culture, things like that.”

PROFILE OF DEFECTORS HAS CHANGED

Mr Han pointed out that most defectors are middle-aged and find it difficult to adapt to a new society. Younger defectors who are attending school tend to fit in easier.

“My father is still having a hard time,” he said.

However, experts said that the profile of defectors has changed in recent years, with a growing number in their 20s and 30s like Mr Han. More “elite” North Koreans have chosen to cross the border as well.

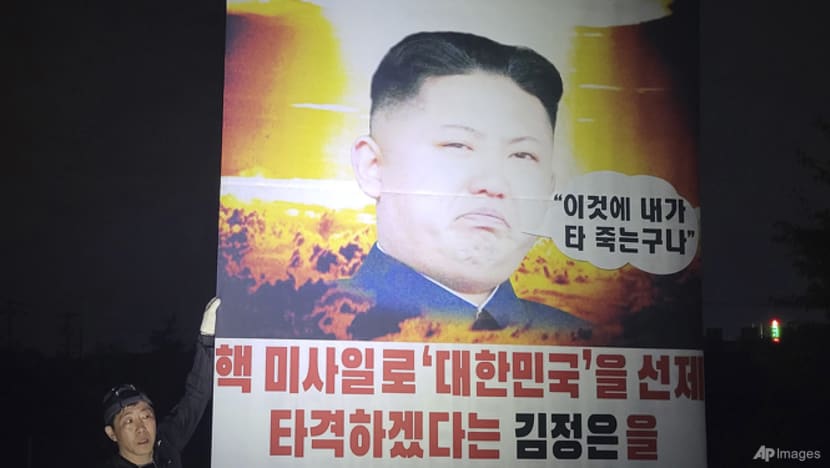

The motivation for fleeing has changed from starvation and economic difficulties to dissatisfaction with the regime and the future of North Korea, especially under its leader Kim Jong Un, said Dr Jay Song, a North Korea researcher and adjunct fellow at the University of Technology Sydney.

In an exclusive interview with CNA last week, South Korea’s Unification Minister Kim Yung-ho said North Koreans know what life is like in the South from secretly watching South Korean dramas.

They then realise the stories they are being told about South Korea, such as being less developed than the North, are not true.

Dr Song pointed out the great risks that defectors take. They first must cross the border to China, where they are in danger of being trafficked and have to hide from Chinese security forces.

“(This) very vulnerable and precarious immigrant status in China will lead them to be exposed to other criminal activities in China as well,” Dr Song said.

“In recent years, the Chinese authorities increased the level of surveillance, especially targeting these North Korean defectors and migrants, so it's extremely dangerous to move within the Chinese borders and crossing the border from China to other parts of the world, including Southeast Asia.”

In terms of whether reunification of the Korean Peninsula is on the horizon, Dr Song said young people in both the North and South do not think they belong to the same nation.

“Unification is not a favourable future for them because it’s very challenging to have a unified identity for all Koreans, unfortunately,” she added.

The two sides are technically still at war despite the Korean War Armistice in 1953.

SEEKING EMPLOYMENT HELP FROM FOUNDATION

While Mr Han’s situation improved for a while, things have become tough on the job front once more. He lost his job at a car dealer when it closed its physical stores due to the pandemic.

He is now seeking help from the Korea Hana Foundation, which offers support like job training and matching, financial aid and housing, on top of a three-month adaptation programme for newcomers.

A survey conducted by the foundation last year showed that employment support remains top on the wish list for defectors. About 22 per cent indicated that they wanted assistance to find a job or launch their own business.

The foundation’s head, Mr Kim Sung Mo, said: “In line with this, the foundation is trying to systematically support employment and startups according to their characteristics and conditions.”

Ms Choi Yoon Mi, who has been a counsellor at the foundation since 2015, said the most common group of North Koreans who defect to the South are women in their 40s.

She noted that it is difficult for defectors to find employment if they lack specialisation, adding: “They often need to lower their sights and focus more on simple labour-related jobs.”

While the job situation has improved for North Korean defectors, with their employment rate hitting a record 60.5 per cent last year, the foundation acknowledged there are more hurdles to be crossed.

Mr Kim said that cultural disparities and educational deficits, as well as prejudices and stereotypes against defectors, remain in South Korean society.

For Mr Han, he said he felt at a loss when he and his father first arrived in Seoul.

“Loneliness seems to hit the hardest,” he added.

“Where I come from in North Korea, the society relies more on word-of-mouth and personal networks since the internet hasn't developed.

“Having lived in such a society and then coming to South Korea, those who can't adapt to this feel isolated and lonely."