IN FOCUS: Why is Malaysian oil giant Petronas under siege and its fate crucial for the country?

Petronas’ business model is under threat and its monopoly over Malaysia’s hydrocarbon reserves is being challenged by the Sarawak state government. This will have wide economic and political ramifications for the country, say observers.

A Petronas flag waves next to Malaysia's flag on Jul 24, 2025. (Photo: CNA/Fadza Ishak)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

KUALA LUMPUR: Petroliam Nasional Berhad (Petronas), the overlord and custodian of Malaysia’s hydrocarbon reserves, is under siege.

Already bruised by industry-wide headwinds of weak global oil prices and lower quality oil fields in more difficult geological locations that are hurting its bottom line, Malaysia’s one-time all-powerful oil giant is facing an existential crisis as it navigates the country’s complex political landscape.

A persistent face-off with Sarawak is threatening the very existence of Petronas, which has been a Fortune 500 Global listing for over 26 years.

The Sarawak state government is demanding that Petronas surrender its role as regulator for the hydrocarbon reserves in the state to its wholly owned Petroleum Sarawak Berhad, commonly referred to as Petros.

Sarawak wants its own special purpose vehicle entity that was incorporated in August 2017 to take a lead role in the development of its hydrocarbon reserves onshore and offshore of the state on Borneo Island.

It is a determined move that would effectively strip Petronas of its role as the sole custodian of the country’s oil and gas reserves nationwide as enshrined in the Federal Constitution in 1974 under the Petroleum Development Act (PDA).

Sarawak’s bold constitution-busting gambit has far-reaching ramifications and represents one of the most serious challenges facing Petronas and the Malaysian economy.

Any break in Petronas’s monopoly would significantly impair the oil corporation’s financial standing, and cause panic in international financial markets because the global financial community holds over RM56 billion (US$13.3 billion) in bonds issued by the Malaysian oil firm.

There would then be a cascading effect on the Malaysia government, which has long been dependent on contributions from Petronas to the national coffers through dividends and other special disbursements.

“This is the most serious inflection point for the (Petronas) group, and how this is managed will have a major impact on the economy,” a senior government official involved in high-level discussions together with Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim told CNA on strict condition of anonymity.

The tension between Sarawak and Petronas has been simmering for about a year, and Anwar has on numerous occasions tried to paint a business-as-usual picture, saying that both sides will settle the dispute via dialogue.

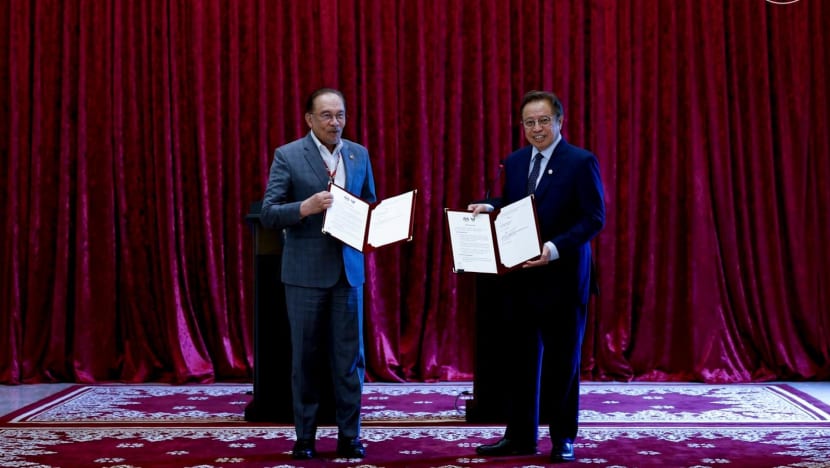

He has also met Sarawak Premier Abang Johari Openg several times for talks, most recently on May 21.

Both leaders then announced that the federal and state governments have signed an agreement that appeared to have put the protracted dispute to bed.

The deal was for Petronas and Petros to jointly develop the country’s oil and gas sectors, and it also set out the parameters and collaborative framework for the two firms.

However, Petronas insiders and other industry players have told CNA that in reality, both firms are still stuck at an impasse and little has changed.

When contacted by CNA, Petronas declined to comment on its protracted troubles with the Sarawak state government.

SURE-FOOTED WITH A DARK SIDE

In a country where state corporations are often associated with financial scandals, such as state-owned steel company Perwaja that lost over RM20 billion in the 1990s during the premiership of Mahathir Mohamad, Petronas is often held up as a sure-footed example of natural resource management.

And in a region where oil companies are known for their financial shenanigans, such as Indonesia’s scandal-ridden state oil company Pertamina, Petronas stands out as one of the world’s most profitable national oil corporations.

Petronas, which started off as the sole regulator and manager of the country’s hydrocarbon reserves, has morphed into a fully integrated oil and gas multinational with interests in more than 30 countries and business activities ranging from upstream exploration and production to downstream oil refining and the distribution of a wide range of petroleum products.

All of this was achieved by leveraging its role as a regulator for the oil and gas sector.

Through long-term production sharing contracts with international oil companies operating in Malaysia, Petronas has been able to ensure that the company and the country retained a lion’s share of the oil profits.

By directly partnering international oil companies in exploration and production activities, Petronas also benefited from the high degree of technological transfer that has allowed it to become a partner of choice in highly capital-intensive oil and gas ventures overseas.

The result: A national oil corporation that operates like an international oil company.

Total assets stand currently at RM766.7 billion and the company posted a profit of RM55 billion on revenues of RM320 billion in the financial year ending 2024.

There is however a not-so-pretty side to this success story.

Petronas has long been tapped to finance pet projects of its political masters, particularly during Mahathir’s first tenure as premier that stretched between 1981 and 2003.

These pursuits include funding bailouts of distressed entities with close political ties, such as the financial rescue of a troubled shipping firm owned by Mahathir’s eldest son Mirzan Mahathir in 1997, and financing pet projects, such as developing the administrative capital Putrajaya, located about 35 km from the capital Kuala Lumpur, that cost RM30 billion.

The oil corporation has also played the role of lender of last resort in two separate bailouts in 1984 and 1989 of the now-defunct state-owned Bank Bumiputra that together amounted to more than RM6 billion.

The tar of politics in Petronas’ otherwise strong record is due to its unique charter.

While the national oil corporation was formed under Malaysia’s Companies Act, a special set of laws were designed to regulate the entity under the 1974 PDA.

Unlike other companies registered under the Companies Act, Petronas is not required to file and publish and file annual accounts.

What’s more, the PDA also stipulates that the oil corporation “shall be subject to the control and direction of the prime minister”.

As a result, over the last five decades, successive governments have increasingly come to rely on Petronas to fund ventures outside of its core business, turning it into the country’s chief fiscal “cash cow”.

To be sure, the Malaysian government has long dominated various sectors of the economy through state-owned entities, such as Khazanah Nasional Berhad and Permodalan Nasional Berhad, that in turn own dominant stakes in several of the largest companies listed in on the Malaysian stock exchange.

Through this model, the government accrues revenues from dividends paid by public listed entity companies, but they pale in comparison to what Petronas contributes annually.

According to RHB Research, apart from dividends of RM32 billion the government received from Petronas in 2024, the government accrued another RM40 billion in the form of cash and tax payments and other contributions.

UNDER THREAT

But Petronas’ business model is under threat.

The global oil and gas environment is fraught with serious problems.

The volatility in international oil markets are crimping profits, while extraction of oil and gas is becoming more costly as discoveries become increasingly small and are in harsher environments.

“There is a logic, an assumption set, and a projection that backs it up. Over time, we have seen this — those who have tracked our history will know that when the fields were easier, our profit before tax margin was around 35 per cent to 40 per cent,” Petronas’s chief executive officer Tengku Muhammad Taufik Tengku Aziz told reporters in early June.

“Today, it is [between] 25 per cent and 38 per cent. These margins are going to shrink further, and the fields are going to get smaller. So, the value-added [Petronas] 2.0 must transform into an organisation that monetises molecules commercially and competitively, not just at home, but also abroad,” he said.

The oil corporation’s overseas expansion has also been patchy.

While Petronas has established a significant global footprint, with 40 per cent of its oil and gas reserves and around a quarter of its production coming from its foreign forays, there have been numerous stumbles.

Petronas previously held a 15.5 per cent stake in an Azerbaijan natural gas project known as Shah Deniz and in 2021 entered a deal to sell its stake to Lukoil of Russia for US$2.25 billion.

But that planned disposal got entangled in a bizarre legal dispute between the Malaysian government and the heirs of the Sulu Sultanate in southern Philippines.

The stakes in Shah Deniz were seized under a French court order in mid-2023.

Petronas maintains that the claims by the Sulu Sultanate and the seizures are baseless, and the corporation is contesting the claim in the French courts. The case is ongoing.

In August 2024, Petronas suffered another setback when the South Sudan government moved to nationalise oil fields and assets after the government there blocked a US$1.2 billion plan by the Malaysian company to dispose of its holdings in the war-torn country.

Petronas has begun arbitration proceedings against the South Sudan government.

In June 2025, Petronas had to deny media reports that it was considering selling holdings in Canada, where the Malaysian company has a major stake in a joint-venture in the resources-rich Montney region.

That report surfaced shortly after Petronas’s CEO Tengku Muhammad Taufik announced that the oil giant, once considered the country’s vanguard of job security until retirement, would be cutting its workforce of 50,000 employees by 10 per cent next year.

HANDCUFFED

For all its troubles overseas, the biggest threat currently confronting Petronas is domestic, where it has increasingly been handcuffed by the country’s topsy-turvy politics.

The increasingly protracted spat between the Sarawak state government and Petronas is rooted in the country’s troubled political landscape.

For almost six decades, Malaysia’s political model was very much a centralised federation parliament system with the Barisan Nasional coalition, led by the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), dominating the country’s 13 states.

But that supremacy ended in 2018 when the UMNO-led government was toppled in that year’s general election, leading to a very fragmented and restive political landscape.

There have been four administrations since the Barisan Nasional’s spectacular ejection from power and the most recent is led by Anwar, who formed a coalition government following an inconclusive national poll in November 2022.

In all the four administrations, the ruling coalition in Sarawak, known as Gabungan Parti Sarawak (GPS), has been a cornerstone in providing political stability to the respective coalition governments.

With its total of 23 parliamentary seats in Malaysia’s 222-member lower house, GPS is widely considered to be critical in keeping together Anwar’s unwieldy coalition government that comprises more than a dozen political parties with diverse ideologies.

Close associates of Anwar acknowledge that the premier considers Sarawak a very crucial cog in his government and any threat of a pullout would very likely trigger a round of horse-trading among restive members of his unity government that would trip the Malaysian premier’s Pakatan Harapan coalition.

“Sarawak is clearly taking advantage of the perceived shakiness in the (Anwar coalition) government with the tacit threat they could pull out if their demands are not met,” said Charles Santiago, a former elected Member of Parliament from the Democratic Action Party, which is also part of the ruling coalition.

Santiago said that he fully appreciated the tough position Anwar is trapped in because of the political considerations he is being forced to juggle, and this is why the prime minister has repeatedly urged both parties to settle the matter through private negotiations.

“He (Anwar) is firefighting alone and is not getting any backing from his other cabinet colleagues. But the point is that this crisis (between Sarawak and Petronas) should not drag on any further and parties should turn to the courts,” he added.

THORNY FEDERAL-STATE RELATIONS

The Petronas-Sarawak spat over the management of resources is also bringing to the spotlight a little discussed political challenge facing Malaysia: The growing tensions in the country’s federal system of government and the increasing uneasy relations with state administrations because of a deeply fractured political landscape.

Over the last two years, the Anwar government has grudgingly consented to many demands from Sarawak, moves that have sharply undercut the authority of the central government.

Apart from granting the state greater autonomy over matters such as health care and education, Kuala Lumpur has also surrendered control of strategic assets such as a major port in the coastal town of Bintulu and a regional airline operation previously controlled by national carrier Malaysia Airlines.

But the dismantling of the 1974 PDA would be near catastrophic financially, not just for Petronas but also for Malaysia.

Sarawak has probable and proven reserves of petroleum representing 60.87 per cent of Malaysia total reserves and the state accounts for 90 per cent Malaysia’s liquified natural gas (LNG) exports that make up a large portion of the national oil corporation’s earnings.

Other states where Petronas has sizable operations are in neighbouring Sabah on Borneo and in Terengganu and Kelantan in Peninsular Malaysia.

While Sabah has cordial relations with the Anwar administration, Terengganu and Kelantan are ruled by the opposition right-wing Parti Islam Se-Malaysia.

“Opposition states will be watching this (the Petronas-Petros) issue closely because all are looking for sources of revenue,” said Ibrahim Suffian, programmes director at Merdeka Centre for Opinion Research.

But he noted that the “other states have limited power to assert themselves the way Sarawak has done”.

Sarawak and Sabah have greater powers compared to the states in Peninsular Malaysia that came together in 1957 under what was called Malaya when independence was obtained from Britain.

The two North Borneo states - and Singapore - joined the federation in 1963 to form Malaysia, before Singapore gained independence in 1965.

That union, which is widely referred to as the Malaysia Agreement 1963, or MA63, granted the two states specific rights and autonomy within the federation, including greater control over the management of its natural resources that has now turned into a nightmare for Petronas.

OPTIONS ARE NARROWING

Over the last nine months, Anwar has repeatedly sought to play down the protracted spat between Petronas and the Sarawak state government.

In the third week of May, Anwar announced that his government had reached an understanding with Sarawak Premier Abang Johari that the role of the national corporation would remain intact.

“Petronas’ role is not diminished. It continues to operate as usual, but now within a framework that also considers Sarawak’s enhanced responsibilities and Petros’ role,” he said after he and Abang Johari signed a joint declaration.

But Petronas officials and executives of foreign-owned oil and gas contracting firms told CNA that the situation is still problematic.

A senior Petronas official noted that employees from its headquarters in Kuala Lumpur have been facing difficulties in obtaining work permits from the Sarawak authorities since the spat began late last year.

“Our options are narrowing, and the PM’s notion that we can resolve this through negotiations with Sarawak is not going anywhere because both parties are coming from very different positions,” said the senior Petronas official who was previously based in Sarawak and spoke on condition of anonymity.

He added that the chief stumbling block in the talks since December has been Sarawak’s refusal to acknowledge the PDA that the state’s own representatives in Parliament had backed in a vote in the lower house in 1974.

Instead, the state government is insisting on falling back on a provision under its colonial-era Oil Mining Ordinance 1958 that stipulates that oil and gas resources found within 200 nautical miles of its waters belong to the state, the official said.

Other industry players added that operating in Sarawak has become increasingly cumbersome, with Petros often challenging the national oil corporation’s role as the sole regulator for industry players.

They noted that Petros has increasingly introduced new regulations and requirements on work processes in exploration and production that were previously decided by Petronas.

A chief executive official of an offshore oil contractor that has had a long relationship with Petronas added that previously it had to deal only with the national oil firm which is also the regulator and “things moved seamlessly”.

“But with Petros increasingly weighing in, there is now another unnecessary layer,” he said.

Former premier Mahathir has also weighed in on the ongoing spat, stressing that Sarawak’s push for autonomy, particularly in the control of oil and gas resources in the state, should go through parliament and not be left to backroom negotiations that could weaken Petronas’ financial position.

“The nation will lose by the arrangements being negotiated between the federal government and the state government,” he was quoted by local media as saying.

But Sarawakians see the issue differently.

“All Sarawakians feel they have been short-changed and deprived by the PDA, the federal government and Petronas,” Abdul Karim Rahman Hamzah, a Sarawak state assembly representative from the ruling party headed by Abang Johari, told CNA.

“We want rights to participate in upstream and downstream industries related to its resources and not just be bystanders,” he said.

“We are not bothered if the oil and gas are discovered in other states, but we bother if it is found within the territory of Sarawak.”

Several senior oil industry executives with long relationships with Petronas said that Sarawak's aggressive stance against Petronas could potentially backfire.

Unlike Petronas, which is seen as a partner of choice for international oil companies in Malaysia and abroad, Petros has yet to build any depth to its technology know-how.

“What Petros has is the legislation of the state on its side, but it does not have the expertise and financial resources that makes Petronas an international player,” said a chief executive of an international consultancy concern that has advised Petronas in the past.

He noted that Petronas “could easily shift gears” and concentrate on developing oil fields and its gas operations in Sabah and overseas.

But there is a catch.

Petronas has long concentrated on development of resources in Sarawak, and any pullback now would not only hurt Sarawak, but Petronas and the national economy.

POSSIBLE SOLUTION

With both Petronas and the Sarawak state government digging in their heels over the dispute, several analysts said that the disputing parties need to find some middle ground soon to break the impasse.

Former law minister Zaid Ibrahim believes that “both parties should turn to the courts to settle the issue”.

Kuala Lumpur-based Kenaga Research has meanwhile suggested that both parties enter into profit-sharing arrangements for the distribution of gas and oil from the state, similar to the model used by gas aggregators in the United States that operate as LNG exporters and earn about a 20 per cent margin on the final selling price.

But the senior Petronas official who was previously based in Sarawak noted that the national oil corporation already has long-term supply arrangements with parties in Japan and Korea for gas extracted from the state and liquefied at the Petronas Bintulu LNG Complex in Sarawak, which is ranked as one of the largest in the world.

“There are so many issues apart from the existing contracts, and ownership of the facilities built by Petronas. All Petros will be doing is acting as a commission agent,” said another Petronas official who has long been overseeing the oil corporation’s international projects.

He added that the prospect of a profit-sharing arrangement could work for new discoveries.

Ibrahim Suffian, programmes director at Merdeka Centre for Opinion Research, told CNA that finding common ground is going to be tough.

“Petros wants what Petronas has and the oil corporation is not going to give it up.”

Editor's note: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the global financial community holds over US$56 billion in bonds issued by Petronas. The correct figure should be RM56 billion. We apologise for the error. Figures on Petronas’ petrochemical reserves and foreign production have also been updated after clarifications by the company.