Amid cheaper and digital alternatives, Japanese traditional name stamps still hold appeal

Using hanko, or handcrafted name seals, as a stamp of authenticity, became a common practice in Japan a few centuries ago and has been required for official business since the 1870s.

Using hanko as a stamp of authenticity became a common practice in Japan a few centuries ago.

TOKYO: For centuries, hanko or handcrafted name seals have been an integral part of Japan’s culture.

Using hanko as a stamp of authenticity became a common practice in Japan a few centuries ago during the Edo period. It has been required for official business since the 1870s.

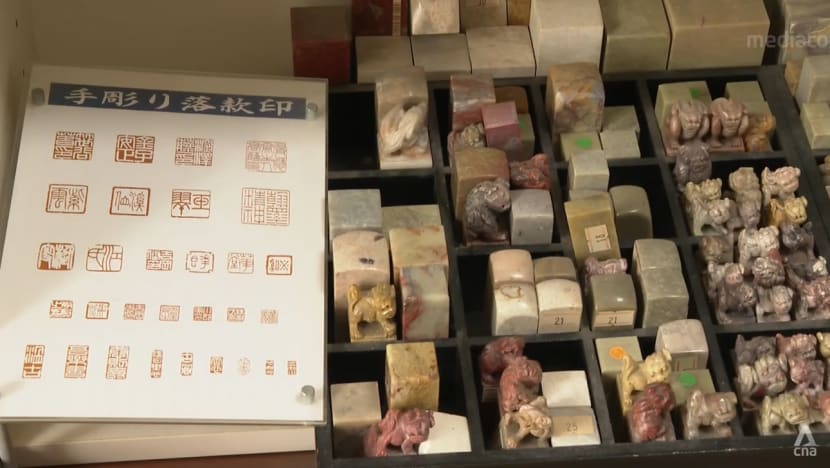

Among the artisans in the trade that involves meticulously carving kanji – Japanese characters – is Mr Tomonari Sanada.

He has been in the business for about 40 years.

Depending on the intricacies of the design and the material used, he takes anything from a couple of hours to a few days to complete one. Painstakingly handcrafted, prices of his hanko can reach up to US$1,000.

“It's one of a kind. There is no other that I would carve in a similar way. That’s most important. There are hanko shops that make everything with a machine and sell to customers. They can be cheap," he told CNA.

Today, from opening a bank account to purchasing property, documents in Japan cannot be processed without hanko. However, the stamps do not have to come from one that is hand-made. Ready-made hanko can be bought off the shelves in the market.

Called sanmonban, these alternatives are the reason why Digital Minister Taro Kono thinks Japan should abolish the practice of using hanko as an official seal of authenticity.

“Cheap hanko, sanmonban doesn’t certify anything. Anyone can buy hanko with (names such as) Kishida, Kono and put hanko on paper. Having hanko on paper doesn’t mean this person is writing or writing this form," he told CNA.

SHELVING HANKO

In 2020, at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, many Japanese found it impossible to work remotely because many documents were still required to be sealed with a hanko. It was at that time that Mr Kono called for hanko to be banished, a move that was considered highly controversial among government agencies.

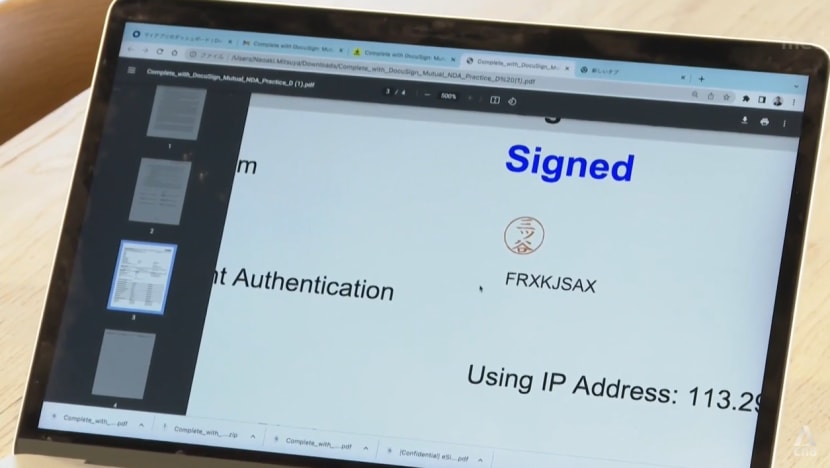

But it resonated with Mr Naoaki Mitsuya, who works for a company that allows organisations to manage electronic agreements. Having entered the Japanese market in 2015, he has only recently started to see more demand for digital hanko.

“As this industry’s expert, I’ve been here for over 15 years. I’ve never heard such a strong comment from the government," said the regional vice president of DocuSign.

A PLACE FOR HANKO

However, even as he pushed Japan towards a paperless future, Mr Kono said it was not his intention to hurt the hanko industry, which has been experiencing a gradual drop in the number of artisans in recent years.

“I am a hanko lover. I have quite a few of them. Whenever people ask me to write something, I actually put a couple of hanko on it, " he said.

Some companies CNA spoke to said that while they are shifting to digital hanko where possible, there are areas where this is not possible, specifically in administrative departments. Mr Mitsuya acknowledged that Japanese clients and customers still need hanko.

Despite selling e-hanko for a living, he said that he also loves traditional, physical hanko and recently ordered an elaborate hanko with his name shaped like a smile.

Hanko, as a craft form and collectible, may still have a place in Japanese society even when the country becomes paperless.

Whatever the future may hold, hanko craftsman Mr Sanada said he is not giving up his trade. To him and many hanko lovers, the unique craft is more than just a seal of authenticity.