‘They are my friends’: In Malaysia, Wolbachia mosquitoes fight their dengue-carrying counterparts

A staff member of the Malaysian Institute of Medical Research releases the Wolbachia mosquitoes at Keramat AU2. (Photo: Rashvinjeet S Bedi)

KUALA LUMPUR: These days, Mr Khasmani Samat does not kill every mosquito that lands on him.

If they are the aegypti species of mosquito, the 76-year-old pensioner chooses to gently blow them away.

“They are my friends now. I can identify them as they have stripes on their legs. The other mosquitoes are wild ones and will be killed without any hesitation,” he told CNA at his home in Keramat AU2, a suburb that is about 15 minutes away from the Kuala Lumpur city centre.

He noted that the aegypti mosquitoes in his neighbourhood are very likely to be infected with the Wolbachia bacteria and are therefore not capable of spreading the dengue virus.

Having been infected with dengue twice, Mr Khasmani wouldn’t have hesitated to kill any mosquito that came near him in the past.

“When I had dengue, I remember seeing the sun even at night. It is not something that I would want to experience again,” he said, adding that his wife was also infected at the same time.

“The only thing you can do is drink lots of fluids. I took crab soup, loads of 100 Plus, papaya leaf juice and other liquids,” added Mr Khasmani, who has four children and nine grandchildren.

The former civil servant said many of his neighbours were also affected by dengue, with Keramat AU2 once a notorious hotspot for the disease.

In March 2017, Keramat AU2 was chosen to be the first locality in Malaysia to undergo a pilot study under the Institute of Medical Research (IMR) on the effectiveness of Wolbachia mosquitoes.

Mr Khasmani said there was annoyance at first with the increase of the mosquito population especially when they were released. But those in the area soon got used to it.

After around six months, things improved, he recounted. “It has been a while since I have heard of a dengue case in my neighbourhood,” he said.

Researchers have found that the Wolbachia bacteria can inhibit the replication of the dengue virus.

The bacteria naturally occur in insects such as flies, butterflies and grasshoppers but are not found naturally in the Aedes aegypti, the most common vector of the dengue virus.

Mr Danial Al-Rashid Harun, a former councillor in the Shah Alam City Council recalled that despite many traditional cleaning and fogging programmes, there continued to be many cases of dengue at high-density flats in Section 7 of the city in mid-2019.

“We were jammed and didn’t know what to do. It was havoc,” he told CNA.

The IMR asked the city council if they were keen to test out the Wolbachia method.

“There were questions about the effectiveness of releasing more mosquitoes but after a while the number of cases really dropped,” said Mr Danial, who stepped down last December.

In October, Health Minister Khairy Jamaluddin, citing analysis by his ministry on 17 localities where Wolbachia mosquitoes have been released, told parliament that 15 of them reported a reduction in dengue cases. The fall in cases ranged between 67 per cent to 100 per cent, two years after the implementation of the Wolbachia method.

USING AEDES TO FIGHT AEDES

The Wolbachia method involves mosquitoes being intentionally released. For someone not in the know, this might seem puzzling.

The IMR still releases these mosquitoes once a week at AU2 Keramat. The area where mosquitoes are released has expanded as compared to the initial pilot study phase.

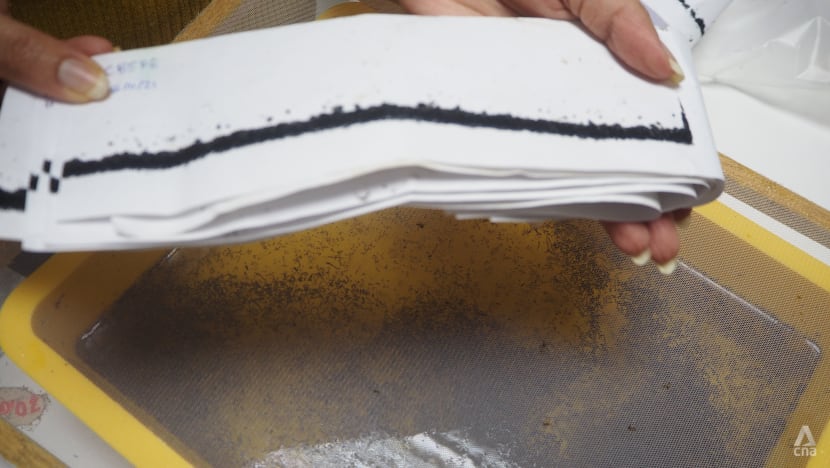

The Aedes aegypti mosquitoes - about 100 in each paper cup – are released around trees, flower pots and drains of the locality. About 2,400 mosquitoes are released in an area equivalent to half a football pitch.

Those in the vicinity of the releases are prone to being bitten.

“We are prepared with our repellent and long-sleeve clothing. If not, you are likely to be bitten,” an IMR staff told CNA during the release of the Wolbachia mosquitoes on a weekday morning at AU2 Keramat.

In the past, the most common methods of fighting dengue were using insecticides and trying to reduce the breeding sites of mosquitoes, but these have not been found to be very effective.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the global incidence of dengue has grown dramatically in recent decades and that about half of the world's population is now at risk.

The global body estimates 100 million to 400 million infections each year.

Related:

After a record high of more than 100,000 dengue cases annually from 2014 to 2016, Malaysia opted to research the use of Wolbachia in collaboration with the University of Glasgow and the University of Melbourne.

At that time, the Ministry of Health (MOH) estimated that the more than 100,000 cases of dengue cost Malaysia US$175 million in 2016.

The first batches of Wolbachia eggs were supplied by the University of Glasgow, which injected the bacteria into the mosquito eggs.

The use of Wolbachia-based control to bring down dengue cases had previously been researched in Australia, Singapore, Indonesia, Thailand, Vietnam, China, Brazil and Columbia.

During the pilot phase, the IMR released batches of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes carrying a particular strain of Wolbachia into the environment at 11 diverse research sites with high dengue transmissions, all in the Klang Valley.

More than 3.5 million mosquitoes and almost 900,000 mosquito eggs were released during the trials.

“We saw a reduction of dengue cases, with the best performance at the clustered high rise or flats.

“The Aedes aegypti carrying Wolbachia are 'good' mosquitoes that prevent the spread of dengue, chikungunya and Zika,” said Dr Nazni Wasi Ahmad of the IMR and the principal investigator of the Wolbachia project in Malaysia.

The data, published in the peer-reviewed journal Current Biology in Nov 2019, showed that dengue cases in 11 sites in Klang Valley fell by 40 per cent to 65 per cent.

The MOH decided to move into the operational phase of the project in July 2019. There are now 30 localities that are part of the programme in Selangor, Kuala Lumpur, Putrajaya, Penang, Kelantan and Melaka.

The IMR measures the prevalence of the Wolbachia population every month at their active sites and on a lesser frequency at the other sites.

Once the Wolbachia frequency in a locality is more than 80 per cent for several consecutive months, further mosquito releases are stopped.

Dr Nazni told CNA that the success of lowering dengue cases at these sites means that fogging no longer must take place here.

REPLACING BAD MOSQUITOES WITH GOOD MOSQUITOES

He explained that Malaysia employs the replacement strategy approach, where both male and female Wolbachia mosquitoes are released into the environment. They would then mate with wild mosquitoes that do not carry Wolbachia.

Male mosquitoes feed only on plant juices for energy and survival. They do not bite and cannot transmit diseases.

Female mosquitoes, on the other hand, need protein from blood for the development of their eggs. To obtain blood, they seek out and bite hosts such as humans.

A male Wolbachia mosquito that mates with a wild female mosquito does not produce any offspring while a female Wolbachia mosquito that mates with a wild male will produce Wolbachia mosquitoes.

Male and female Wolbachia mosquitoes that mate with one another will also produce offspring with Wolbachia.

In contrast with Malaysia, Singapore only releases male Wolbachia mosquitoes. This is a population suppression approach.

Dr Nazni said while it might be effective in Singapore, it is not feasible for a larger area such as Malaysia.

“The spread of Wolbachia is dependent on the release of females as it is transmitted maternally. By releasing females, Wolbachia will be introduced into a population,” she said.

Currently, the IMR breeds its own Wolbachia mosquitoes which it then releases into hotspots or supplies to the various health departments.

“We have to conduct our quality control very often and ensure that the mosquitoes are genetically the same as those found outside so that they can mate,” said Dr Nazni, who stated that community involvement is vital to the success of the project.

COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION STILL KEY TO FIGHTING DENGUE

Indeed, the Wolbachia method cannot work in isolation.

Public health expert Professor Lokman Hakim Sulaiman said that a combination of methods is needed to fight dengue, with the key being reducing Aedes breeding and density through community empowerment and participation.

“Aedes is highly domesticated and breed within and surrounding human habitation,” said the professor of public health at the International Medical University.

He said that while the Wolbachia is an innovative and plausible approach, it is still methodologically and logistically challenging for mass production and distribution.

The number of dengue cases has dropped dramatically this year, but Prof Lokman said this could be due to the natural dengue epidemiological cycle that sees peak outbreaks every four to seven years.

As of Oct 23 of this year, the cumulative number of reported cases in Malaysia was 21,308, with 16 deaths reported.

This is a significant decrease of 74 per cent compared to 80,590 cases reported during the same time frame last year, where 133 deaths were reported.

Despite the reduction in the number of dengue cases, Dr Nazni of IMR said that the fight is far from over.

In the future, IMR is thinking of collecting mosquitoes from sites with high populations of Wolbachia such as Mentari Court in Petaling Jaya and transferring them to other sites.

“Of course, we need to be cautious and only collect from areas which are not hotspots and where there are no dengue cases,” she said.