When water hides an invisible threat: The scars of arsenic poisoning in Nepal, and hope for new 'change-makers'

Children in Nawalparasi use a hand pump to draw water from a tube well. (Photo: Makhan Maharjan)

NAWALPARASI, Nepal: When spots first started appearing on his body, 59-year-old Ramprasad Yadap had no idea what they were.

“I knew that there was something (wrong) ... but I didn’t know what it was,” said Mr Yadap, who was 40 when the onset of arsenicosis symptoms began. “I was surprised.”

A chronic illness resulting from prolonged ingestion of high levels of arsenic over a long period of time, arsenicosis or arsenic poisoning often takes years to manifest.

Symptoms include skin problems and arsenicosis can eventually lead to cancers of the skin, bladder, kidneys and lungs.

Mr Yadap’s ancestors had for decades lived in Ghanshyampur village, a small settlement in the Nawalparasi district of southern Nepal. But none of them had experienced this problem before.

All his life, he had used hand pumps to draw water from shallow tube wells. He did not know that the water contained arsenic.

Mr Yadap was eventually diagnosed with arsenicosis when he participated in a mobile health examination programme for residents in 2012.

“It wasn’t a big attack, but happened slowly,” he added. Eventually, the arsenicosis resulted in gangrene in a limb, which had to be amputated thrice.

“I feel very sad,” said Mr Yadap, who used to be a farmer but has now stopped working for about five years. “Now staying here (at home)... I'm like a burden to my family.”

AN ARSENIC "HOTSPOT"

In Nepal, arsenic is naturally occurring. The sediments deposited by Himalayan rivers thousands of years ago are thought to be the source of arsenic in groundwater in the Terai region of Nepal, where Nawalparasi is located.

“Arsenic can be found in high concentration at one place, but 10 metres away there might not be arsenic,” said Dr Makhan Maharjan, who worked on arsenic-related projects and researched on arsenic in Nepal for over two decades. “It depends on the geology.”

More than half of Nepal’s total population lives in this region, where it has been reported that 90 per cent of the population rely on groundwater as their major source for drinking water.

In the past, dug wells - which were mostly arsenic-free - were mainly used in the Terai.

These open wells had a wide diameter, exposing the water to the air and allowing iron in the water to be oxidised. Arsenic in the water would then be adsorbed on the iron oxide precipitates, lowering the concentration of arsenic in the groundwater.

But because the water came into contact with the external environment, this meant contamination from other sources and resulted in the spread of waterborne diseases.

To solve this issue, many shallow tube wells were installed to provide drinking water. These tube wells could be manually operated by hand pumps which would draw shallow groundwater for drinking.

But the issue of arsenic poisoning rose to the fore in the 1990s after Bangladesh and Nepal’s neighbouring West Bengal reported mass poisoning cases due to arsenic-contaminated groundwater.

As a result, Nepal’s Department of Water Supply and Sewerage (DWSS), with help from the World Health Organization (WHO), conducted a 1999 study on possible arsenic contamination in groundwater of various districts in the region.

The study would eventually confirm the presence of high levels of arsenic in several areas.

In a 2004 report by the Groundwater Management Advisory Team and World Bank, it was said that about 20,000 shallow wells equipped with hand-pumps had been tested.

About 30 per cent showed concentrations above WHO-recommended standards of 10 parts per billion (ppb) and 5 per cent were higher than the Nepalese national standards of 50ppb. Higher values (over 100 ppb) were found in four districts, of which Nawalparasi was “most affected”.

A 2016 publication by the Japan International Cooperation Agency, DWSS and the Environment and Public Health Organisation estimated that approximately 80,000 people may be using arsenic contaminated water for daily drinking purposes in Nawalparasi.

While there is currently no official data on the number of arsenicosis patients in Nawalparasi, Dr Maharjan estimates it to be in the hundreds.

“Nawalparasi is called the hotspot of arsenic contamination (in Nepal),” he noted.

“From all over the world … researchers used to come to this place for collecting samples and the examination of people.”

FROM WATER FILTER TO RICE CONTAINER

One of the ways to tackle arsenic contamination is the distribution of household water filters. These filters are seen as a short-term mitigation option and help to remove arsenic in water drawn from shallow tube wells.

While these filters are in theory effective, issues with usage have arisen over the years, noted Dr Maharjan.

Clay filters for one, would break and have seepage issues. Plastic filters, on the other hand, posed other problems. While water drawn straight from shallow tube wells would be cool, water poured through the plastic filters would eventually heat up during the summer months.

“The water becomes very hot in the plastic container, so they didn’t like it,” he explained. “When we pour water in the (concrete or plastic) filters, some dust can also appear in the water. They see that and say that it's dirty,” said Dr Maharjan.

He has seen first-hand how filters have been abandoned and used for other purposes. Some use them as storage bins, others to keep rice.

People prefer the convenient option of simply drawing water from the shallow tube well rather than collecting the water from the same well, pouring the water through the filter, and in some instances, waiting for a while for clean water, Dr Maharjan said.

Instead, most want the local government to set up a system where clean water is piped into homes and can be accessed through taps.

This is already being done in the district headquarters of Parasi. Water is extracted through the processes of deep-boring, stored and piped to the community. This has already been done for a number of years.

However, for this to be done throughout the area will require a lot of money as well as proper planning, noted Dr Maharjan.

To fully understand the scope of the issue, a comprehensive study needs to be conducted, he added.

“There is a need for follow-up studies on arsenic level, health status of the people. That will be helpful for sustainable arsenic mitigation,” Dr Maharjan explained.

EDUCATING "CHANGE-MAKERS"

Recognising the need to educate the younger generation and set up water treatment facilities, Dr Maharjan proposed the idea of a clean drinking water facility in a local school to NEWRIComm, the philanthropic arm of the Nanyang Environment and Water Research Institute (NEWRI).

Today, NEWRIComm has contributed to the building of large bio-sand filter systems in two local schools.

In the filter, iron nails are exposed to air and water, causing them to rust and produce ferric hydroxide particles, which adsorb arsenic when arsenic-containing water flows through the filter.

The arsenic-loaded iron particles are then flushed into the sand layer below. Because of the small pore space in the fine sand layer, the arsenic-loaded iron particles will be trapped in the top few centimetres of the fine sand layer. Arsenic removal in these 1,000 litre tanks is in the range of 85-95 per cent.

Compared to the household filters, this system is faster, requires less manpower and has a larger capacity.

“We reviewed it and I thought it was a great way to go,” explained NEWRI executive director Shane Snyder.

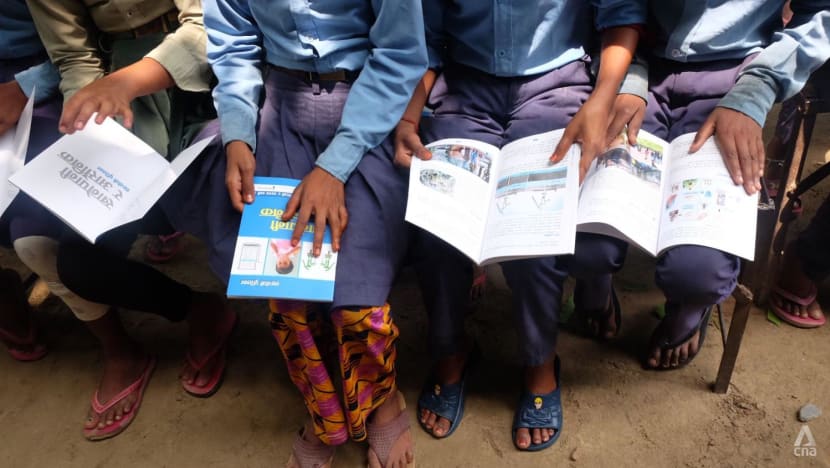

Part of the project also includes various activities such as teaching management how to maintain the filter system as well as educating students through a booklet on arsenic.

“This is a very unusual project for NEWRI compared to the ones we're doing in Thailand, Indonesia, which are usually very high tech, very engineering focused," added Dr Snyder, who stressed the importance of the educational aspects of the project.

Dr Maharjan noted that awareness of the issue is increasing. The younger generation will be “change-makers”, he added.

“Students are very important. They are the change-makers … If we teach students about arsenic, about water quality, the importance of safe drinking water, then they take messages home to their family, and they will share with the parents and other family members,” he said.

“From that family, it goes to the neighbour's house. And so then it will spread in the community.”

However, not everybody is convinced of how serious the problem is.

“When arsenic is dissolved in water, it has no color, no smell, no odour, no taste, nothing. It is very difficult to convince them … People may ask that we are drinking from our (place) where our grandparents drank. And nothing happened to them,” explained Dr Maharjan.

“In any community, if some people are found with symptoms, then it becomes easier for us (to explain the situation). If there are no people (who suffer from arsenicosis), then it's difficult, they don't believe it.”

Ms Samjhana Chaudhary, who is deputy mayor of Ramgram, one of the municipalities in Nawalparasi, said that she plans to raise the issue at the national level, arrange more programmes at a local level to “mitigate” the issue as well as request for foreign help.

Meanwhile, the issue remains a complex one.

Ms Chaudhary noted that some cannot afford water filters, and continue to rely on hand pumps to draw water from dug wells.

“The economic condition of the people here are mostly from poor backgrounds, they can’t afford the filter for their homes,” she noted.

Shree Saraswati Secondary School student Sandip Yadav recalled how his parents were not fully convinced that they needed a bio-sand filter for their tube well. The main stumbling block was the cost of the filter, which would be about two weeks' wages for his father, a mason.

But eventually, with the help of his head teacher, the 17-year-old made his case for one.

"I spoke to my father about this matter (about arsenic), and he realised that every year we were falling ill (on occasion). So he decided we need to have this filter at home to be safe from the problem," he explained.

Ms Chaudhary added: “I am not able to take out hand pumps because it is a prime source of water here. It is situated in every house. The people are using hand pumps for various purposes - washing clothes, irrigation and many more (things)."

“First of all, we need to have a full set-up of pure drinking water over here for every house, for each and every family member. Then after that we’ll only be able to look at that (removing the hand pumps).”