Poverty forces families in Myanmar to ditch their elderly

“The old woman was left in the dark, tainted with faeces and urine,” recalls a social worker, who warns that elderly abandonment is on the rise. Part 3 of a regional series on elderly poverty.

Widow Daw Hla Than, 75, makes a dollar or two for a massage that lasts as long her clients desire. (Photos and video: Lam Shushan and Ray Yeh)

YANGON, MYANMAR: With weak hands, widow Daw Hla Than, 75, begins kneading the flesh of the woman lying on the floor of her wooden hut.

On good weeks she gets a few jobs like this, earning a dollar or two, sometimes just 50 cents, for a massage that lasts as long her clients desire. Other times, people take advantage of her - like her landlord who always asks for massages and never pays.

But most of the time, she doesn’t even ask for payment, for she thinks she’s not good enough to be paid.

“Sometimes I ask my customers if my massage is effective and they say it’s okay. Some of them are so fat, my hands are not strong enough,” she said.

She added: “I just expect tips, but some of them are too poor to pay me.”

In neighbourhoods like this where everyone is barely scraping by, poverty at this level makes ageing a pressing social issue, especially when there is little or no government support for an increasingly neglected elderly population.

In Myanmar, most seniors rely on their family for support. But as the country becomes more urbanised, this arrangement could put them in a very precarious position once traditional family structures start to break down.

As it is, 60 per cent of its people over the age of 60 live on less than US$3 per day, according to UN statistics, and fewer than 1 in 5 have any savings at all.

So for Daw Hla, whose children from her first marriage have died, her masseuse work is about survival – paying off the 50,000 kyats (S$50) a month for rent and utilities, while she cooks and cleans for her three orphaned grandchildren.

Her three surviving children by her second husband (also dead) are too poor to give her more than pocket money when they see her on the rare occasion, she says.

THE LAST GLORIOUS GENERATION

Researchers warn that this societal transformation is happening fast: While the elderly make up just 9 per cent of the population today, this is projected to triple by 2050 to about 25 per cent.

Couple these figures with persistent poverty and falling fertility rates, and the sufficiency of the family care model is increasingly under challenge - with critics concerned that the government is ill-equipped to handle the surge of seniors in the near future.

But it is not entirely the current government’s fault that social welfare systems are not up to scratch - after all it inherited decades of neglect when it took over in 2016.

For over 50 years under military junta rule, international sanctions cut Myanmar off from the rest of the world, even as the country was dogged by internal conflict and corruption.

What was once one of Southeast Asia’s wealthiest countries became one of the world’s most impoverished, and the last generation to see Myanmar in its glory days are now in their silver years - except there is nothing so “silver” about their lives now.

Buddhist teachings have traditionally emphasised respect towards the elderly, and on the surface it seems like family structures are still strong, with 86 per cent of elderly folks reportedly living with family.

But cases of abuse and abandonment are on the rise, so much so that a law was enacted in December 2016 to address the issue. The law sets out to protect the rights, health and economic well-being of the elderly.

Daw Khin Ma Ma is one of the lawyers who worked on drafting the law, and she also runs a nursing home for the elderly who have been abused or abandoned. She recalls an incident that left case workers in shock.

“We visited a home where the old woman was left in the dark, tainted with faeces and urine.

“They gave her just one bottle of water, but she couldn’t reach it. They didn’t put the bottle next to her because they didn’t even want to go near her. She was dehydrated and smelled so bad.”

“It was such a shame. Such a shame on our society,” she said.

WATCH: More elderly abandoned in Myanmar (2:13)

CATCH-22 OF POVERTY

The problem, Daw Khin says, is the lack of structural support for the elderly once they get sick or too old.

“Poverty is at the centre of all this... if an elderly person suffers a stroke, they become a burden. The family still needs to make their living every day, children have to go to school. Who will take care of them?”

Some mentally-ill folks are simply driven somewhere and abandoned by the side of the road, unable to tell rescuers where they live.

Other times, seniors are found literally thrown into a rubbish pile, beaten and left for dead. “There have been so many terrible cases that strip off human dignity,” Daw Khin said.

It’s a catch-22 situation - while poverty has rendered many families unable to care for their ailing parents, the attempt to escape poverty has driven others to move away from home or to look overseas for better job opportunities, leaving their elderly parents by themselves.

‘DON’T CRY WHEN I DIE’

Daw Hla, the token massager, can count herself one of the luckier ones, for she still has her health.

But having to run a household by herself at her age is not easy - especially when her two grandsons aged 18 and 20, who earn 6,500 kyats (US$5) a day as bricklayers, hardly contribute to household expenses.

“The older one drinks a lot and he’s kind of a liar. He spends all his money and leaves almost nothing for me,” she said.

For extra money, she scavenges for recyclable trash to sell, but her grandchildren don’t like her doing that because it is “shameful”.

“I scolded (my grandson) yesterday. I said ‘your income is not good enough for us. I can’t stop working because of you. Don’t cry when I die’.”

WATCH: Daw Hla’s story (5:22)

The clothes that she irons, however, do not obviously reflect the level of their poverty: A smart flannel shirt for her grandson, a pink princess dress for her 8-year-old granddaughter.

“I have no problem wearing hand-me-downs, but I want them to have new clothes,” she said as she carefully tucked them away.

Of course she loves her grandchildren, she adds. “If they only cared for me as much as I cared for them, my life would be good.”

Life was not always this way for her – her first husband was a traditional dentist who did well. But she is like most wives in the older generation who relied on their husband’s income; the men tend to die earlier, and the women go on to far outnumber the men in the ranks of the elderly poor.

But for Daw Hla, the thing that hurts most is family turning against her. “My sister in the village is rich as gold. She drives a car - but she never gave me a penny. She ignores me. I took her photo and I burnt it,” she said, her voice growing weak.

“I feel so sad that my own sister would treat me like this.”

NO GOOD STRATEGY MOVING FORWARD

Family feuds and deaths are facts of life. But increasingly, young couples in Myanmar are choosing not to have children, which cuts out altogether the option of having family take care of them when they’re old.

This also means that the government has to create the right social structures now to brace for the wave of senior citizens in the future, observers note.

Certainly, this problem with ageing is happening in most developed countries, but as Daw Khin put it, “(those countries) can handle the problem because they are developed. But our country is less developed” and may not have the resources to support an aged society.

Financially and administratively, the government is limited. Just last year, the Ministry of Social Welfare proposed a universal pension of 25,000 kyats (S$25) for citizens over 65, but had to cut back on its plans because of insufficient budget.

Eventually, it compromised on a monthly pension payout of 18,000 kyats (US$13) for seniors over 90 years of age. The average life expectancy in Myanmar is 67 years.

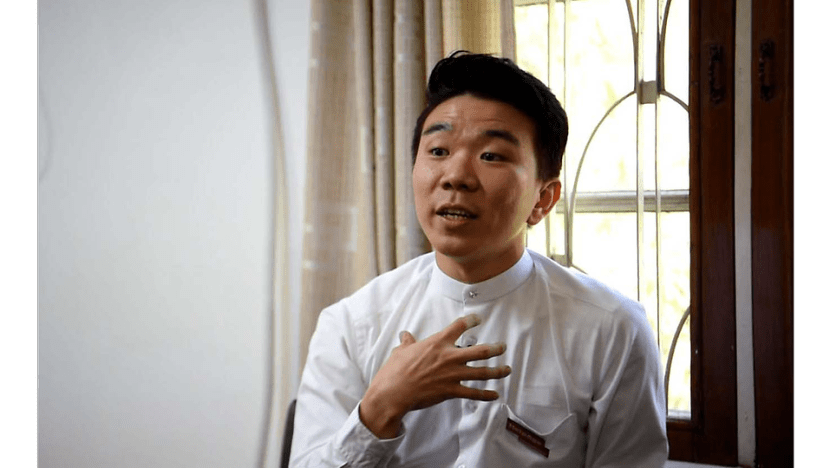

On the administrative side, aid group HelpAge International works directly with the Ministry of Social Welfare in creating policies for the elderly. Dr Hein Theht Ssoe, who is the Social Protection Programme manager at the NGO, says one of the biggest challenges has been in data collection.

According to UN statistics, 25 per cent of the population live under the poverty line. But news reports in Myanmar have reported that figure to be up to 80 per cent.

“It’s very difficult to say who are the poor, and who are the most poor. We don’t have a clear understanding of what poverty is in Myanmar,” said Dr Hein.

WITHOUT STATE SUPPORT, SENIORS HELP THEMSELVES

With all these limitations, one of the things at the top of the agenda for HelpAge is for the elderly themselves to embrace independence, or co-dependence in some cases.

Just an hour from downtown Yangon, a little neighbourhood bustles with energy like that of a start-up town. Small businesses are springing up on every street corner, fuelled by micro-financing and a great exchange of ideas – among seniors.

Through a programme called the Older People’s Self Help Group, HelpAge trains seniors to form a network of support for each other, which encourages them to keep active both economically and socially.

“The approach is to teach them how to stand on their own and to help their peers,” said Dr Hein.

With loan programs structured by HelpAge, seniors have co-started businesses from soap-making to betel nut stands. Some even conduct their own events to raise funds which get redistributed into their businesses.

Programme coordinator Ms Phyu Sin said: “If older people still can contribute to themselves, their family, their community, they should do it.”

And these activities have given them a new lease of life. One of the seniors at a townhall meeting said: “We’re kinder to each other; we almost forget that we’re getting older!”

Volunteers from the village also conduct routine visits to the elderly who are homebound to perform basic health assessments.

With the programme successfully running in 125 villages around Yangon, the government has caught on to this and plans to replicate it on a national level.

CREATE A SAFE ENVIRONMENT FOR SENIORS

But many more, meanwhile, struggle along mostly on their own.

“I never want to trouble anyone,” said Daw Hla. The 75-year-old grandmother adds that she has some sort of pension arrangement with the community head which involves her contributing 500 kyats (50 cents) a month.

“I have no worries about my funeral, (the community) will arrange everything for me,” she said.

To die alone is a dark mark on human society, and it is such thoughts that drive people like Daw Kin to push for more awareness of elderly rights. “We need to educate people that the elderly must not be treated this way in a civil society,” she said.

Yet is there any way out, when it is the most desperate of circumstances that drive families to act this way towards their elderly folks?

“The best thing we can do is to work together with the ministries to work out the priorities in creating a safe environment for older people in the future,” said Dr Hein.

At 30, he has given up a career as a medical doctor to work on improving the plight of seniors - and it seems prescient acknowledgement of the fact that the young of Myanmar today will decide how well, or badly, they age tomorrow.

“When we formulate policies, our very first priority is in preparing the younger generation. Because they will be old in the next 20 to 30 years,” he said.

For now, all someone like Daw Hla can do is prepare for the inevitable. “Sometimes the community head comes around and shouts out greetings, and I would just shout back: ‘Make sure you help at my funeral!’” she said.

This is part of a CNA Insider series exploring the issues of elderly poverty in Vietnam, South Korea, Singapore and Myanmar.

To read more: Vietnam's ticking time-bomb of elderly poverty and South Korea’s elderly who will ‘work until they die’