After hottest summer in 174 years, how prepared is Asia for more extreme heatwaves?

There could be changes in agriculture and other outdoor work, government policies, urban cooling demands and the way people live. The programme Insight looks at what has been happening in parts of East Asia as the weather wreaks havoc.

In many parts of China, the temperature climbed above 40 degrees Celsius last summer — and again this year.

SICHUAN and SEOUL: Last year, when China experienced its worst heatwave since national records began in 1961, the impact on Wang Guoning’s maize farm in Sichuan province was devastating.

“The maize was so dry it resembled tinder, like it could ignite. So many plants died,” recalled the 33-year-old. “Basically, everything was ruined, and we had no income.”

This summer, the heat returned with a vengeance and even hit 52.2 degrees Celsius in China’s north-west Xinjiang province. Several provinces including Sichuan experienced drought and forest fires.

Having learnt from experience, however, Wang started planting more than 20 days earlier this time, producing a crop prior to the adverse conditions. “We managed to (get) the … timing (right),” she said. “So we’ve cut our losses due to drought.”

Nonetheless, China saw a drop in its summer grain harvest. Thermal stress causes maize, for instance, to crop early, which means smaller corn kernels than usual and thus reduced yields.

Other grain-growing nations, from India to the United States, have also struggled with extreme weather. If these conditions persist, maize yields could decline by almost a quarter by the end of the century.

As maize is a cereal crop consumed in large parts of the world and has a wide range of uses, food affordability will also become a challenge.

“We use it for human consumption (and) for animal feed. (It’s) useful for ethanol production and also for industrial use,” cited CropLife Asia executive director Tan Siang Hee.

Around 60 per cent of the maize grown worldwide is used as animal feed. If production volumes are affected and corn prices rise, so too would meat prices.

Chicken, for example, requires about 2.5 kilogrammes of grain for every kilogramme of meat, according to Tan. “A 10-cent increase (in) your grain input will be 2.5 times amplified — even at the farm level — per kilogramme of meat,” he said.

The impact of heatwaves on the farm animals themselves can be debilitating.

“The chickens might eat less and thus take longer to mature,” cited Sichuan chicken farmer Cheng Xiangan. It does not help that Jiuyuan black chickens, the breed he raises, are “a tad ill-tempered”.

The worse the weather conditions, the crabbier they get, just like humans. They fight daily. When they reach sexual maturity, they fight more, and there are deaths.”

He has added fans to his sheds and a ventilation system to the roofs for better air circulation. It has improved the interior temperatures, he told CNA programme Insight.

The occurrence of extreme-heat events will grow, however, with increasing global warming, as suggested in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s latest assessment report.

WATCH: Asia’s hottest summer in 174 years of records — Are we prepared for more heatwaves? (46:03)

This year saw the world’s hottest summer (June to August) in 174 years of record-keeping, according to the US’ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. July, for instance, was 1.18 deg C warmer than the month’s average between 1951 and 1980.

As heatwaves get more intense, there could be changes in not only agriculture but also other outdoor work, government policies, urban cooling demands and the way people live, as recently seen in parts of East Asia.

HEALTH OF FARMERS AFFECTED TOO

As with plants and animals, extreme heat can be deadly for farmers. According to research in the US, agricultural workers are 35 times more at risk of heat-related death than most other workers.

It is even more of a problem in countries with an ageing population, like South Korea.

As the young eschew agriculture, almost half of the country’s farm workers are now aged 65 and over. And this age group is particularly vulnerable to heat stress.

With the soaring temperatures this summer, at least 27 people in South Korea had died by early August, and many of them were elderly farmers.

“Even if it strains the body, they have no choice but to do (the work),” said Cho Chae-woon, the village chief of Deokpyeong-ri. “There’s a shortage of labour in farming.”

But with temperatures in his village exceeding 38 deg C during the recent heatwave, he would fire up his public address system four times a day to warn residents of heat-related illnesses.

“If there’s anyone still working right now, please stop and come to the cool shelter,” he would intone. “Get rest, and try to keep your work (to) the morning and evening hours.”

To beat the heat, the village hall has been converted into a refuge where air conditioning, paid for by the government, keeps the temperature at 25 deg C.

“(The elderly) don’t turn the air conditioner on (at home) because of the bills. So by … having the elderly come (to the shelter), we turn on two units here rather than one in each household,” said Cho.

“Looking at the big picture and our country as a whole, that’s more advantageous, and it also reduces energy use.”

For chilli farmer Hwang Jongwoo, sometimes it gets too hot even before noon. He may take a break until the heat lets up, but this means leaving his fields untended. Heat stress has already reduced his harvest.

“We’re always worried about our crops,” he said. “(Other) people can just relax, but when it comes to our … crops, (they) are often heavily affected.”

TOUGHING IT OUT IN THE CITIES

Away from the farms, it has also been a gruelling summer for some workers in urban centres.

Hong Sung-wan, for example, is perched on a cherry picker for several hours a day, installing network cables for South Korean broadcasting company LG HelloVision, “doing something that someone must do under the hot weather”.

“When I have to stay (by) the utility pole for an hour and a half or two, sometimes I get dizzy,” he said. “Whenever that happens, I think about my family, my colleagues around me, and overcome it.”

It could be an episode of heat exhaustion, which occurs when the body overheats. At worst, it could lead to heatstroke, a potentially fatal condition.

Hong feels he must tough it out. “The workers feel that they can’t help but do their jobs,” said the 51-year-old, who has been on the job for 20 years.

Heatwaves cost billions in productivity losses, however.

At 33 to 34 deg C, work performance could drop by half for those in physically demanding jobs, according to Nicolas Maitre, lead author of the International Labour Organisation report on the impact of heat stress on productivity.

In Seoul, the government made changes in policy after 2018’s record-breaking heatwave killed 48 people across the country — at least for workplaces managed publicly by the city.

Hwang Sung-won of the Safety and Disaster Prevention Division gave the example of workers who must work eight hours a day to get a daily wage of, say, 150,000 won (S$150).

“If they have to take a break from 2 p.m. to 5 p.m. owing to a heatwave that exceeds 35 deg C, those three hours will be considered working hours,” he said. “They’ll still be paid the day’s wage.”

The city does not, however, enforce such a policy for workplaces owned by private companies. “They probably avoid the peak time of 2 p.m. to 5 p.m. and pay the wages according to the hours worked,” Hwang surmised.

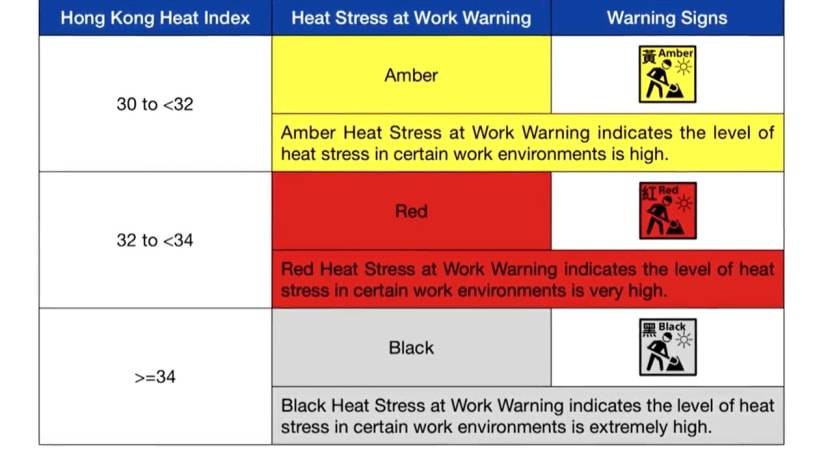

Over in Hong Kong, which just had its hottest summer on record, the Labour Department released anti-heatstroke guidelines this year based on a three-tier warning system.

When an amber warning is in effect, workers with a moderate physical workload, for instance, are advised to take a 15-minute break every hour. There are also red and black warnings, signifying “very high” and “extremely high” heat stress respectively.

Construction workers are especially at risk, often having to toil while exposed to the elements. The new guidelines are not, however, legally binding.

“The most troublesome aspect for us is that we work outdoors — at the construction site — most of the time,” said Lee Kwong-sing, a safety adviser in the Hong Kong Construction Industry Employees General Union.

“We can’t avoid it. And the only thing we can do is to enhance ventilation and provide more shade to keep the workers from feeling too hot.”

POOR AND FEELING THE HEAT

For some others, staying indoors does not offer much relief. In the cramped quarters that impoverished Hongkongers commonly live in, ventilation is poor.

In the neighbourhood of Sham Shui Po, retiree Wong Kwai Hoi resides in a flat measuring about 65 square feet, roughly half the size of a standard parking space in Hong Kong. It does not even have a window.

“It not only affects my mood, but also makes life miserable. It’s so unbearable,” said the 65-year-old. “Sometimes I feel so overheated that I become dizzy and have to take medication.”

Dense housing is found across Hong Kong, a concrete jungle that exacerbates the heat build-up through something called the urban heat island effect. In extreme cases, cities can be 10 to 15 deg C hotter than their rural surroundings.

Wang has an air conditioner, but to save money, he does not use it. He pays more than HK$3,000 (S$520) in rent and utilities and receives a government subsidy of a little over HK$2,000, which he regards as insufficient.

“If I spend several hundred dollars on electricity bills, it’ll affect my living expenses and make my life even more difficult,” he said. “I won’t even have money for meals.”

In South Korea, the destitute also bear the brunt of the hot weather. There are around 14,000 homeless people across the country (as at 2021), and with no permanent shelter, they are particularly vulnerable to heat-related injuries.

“Any problem of extreme weather will always hit the most vulnerable in society,” noted environmental historian Fiona Williamson at the Singapore Management University.

“Maybe they don’t have access to air conditioning or some of the things (with which) wealthier people would be able to mitigate the impacts of heat.”

For those in Seoul who are a high-risk group, volunteers from the Seoul Bridge Centre would invite them to stay at the centre’s emergency shelter — which provides water, food and, importantly, air conditioning — from 7 p.m. to the next morning.

But with this year’s heatwave posing “a very serious problem”, the centre has had to extend its services, said its chief, Oh Seung-chul.

“We’ve been keeping the centre open 24/7 so people can come here to rest and cool down from the heat anytime.”

As the earth heats up, what is needed is education “so people can be informed when they should be outside and when they shouldn’t be”, said Earth Observatory of Singapore director Benjamin Horton.

“If they’re outside in the hottest parts of the day, they need to be hydrated. There needs to be cooling centres so they can escape the heat and keep themselves safe.”

COMPOUNDING THE PROBLEM

Indeed, temperatures and the use of air conditioning have risen in tandem.

In China, energy demand for space cooling has risen, on average, by 13 per cent a year since 2000, compared with about 4 per cent globally.

In Southeast Asia, the number of air-con units is projected to grow from around 50 million in 2020 to as many as 300 million in 2040.

In South Korea, some of its growing demand will be funded by the government, after the ruling People Power Party agreed in June to expand its energy bill support scheme to around 1.135 million low-income households, from 837,000 previously.

To further help low-income residents endure the heat, the Seoul city government said it will subsidise the installation of air-con units in one-room dwellings — as small as 2 square metres — called “jjokbangs”.

Most of these residents subsist on a “basic living” subsidy from the government. “The residents are hoping for air conditioning … so that they can have both warm and cool air in the winter and summer,” said one resident, Cha Jeseol.

But the cost in energy is adding to the heat problem. Power demand in South Korea surged in August to a record high. As with many parts of Asia, the country’s electricity is still mainly generated by fossil fuels.

“Therefore, we need to think about different means of reducing our heat in the cities,” said Horton.

In the search for other solutions, architects and engineers want to construct buildings that cool themselves, such as Gaia — Asia’s largest timber building — at Singapore’s Nanyang Technological University. As a construction material, wood does not trap heat like concrete does.

The building’s air-con system saves energy through passive cooling: pushing cold water through coils to chill the surrounding air, instead of using mechanical ventilation. Designed with natural airflows and with solar panels on top, Gaia is a zero-energy building.

Over at the National University of Singapore, the Heat Resilience and Performance Centre is studying the effects of temperature on the body, which will be important to understand if heatwaves become commonplace.

Some of the research involves helping people to cope in an increasingly warm world.

“We haven’t had to deal with the types of heat … that we’re having to deal with now,” said Williamson. “This is something that’s very new to us. We’re used to maybe dealing with things like flood and droughts.”

But even now, floods continue to wreak havoc. The arrival of Typhoon Doksuri in late July brought the heaviest rains in the Beijing region since records began 140 years ago.

As streets and shops in the capital flooded, authorities decided to take drastic measures. Officials in bordering Hebei diverted the flood waters to the province, reported The New York Times.

The move further inundated Zhuozhou, a city in Hebei that was struggling to contain its own floods after a levee had broken and a local river had overflowed.

With downstream cities flooded to save Beijing and around 1.54 million people in the province evacuated, there has been an undercurrent of division.

The government has since “pre-allocated” 1 billion yuan (S$187 million) for flood relief efforts. Heat and tropical storms are closely linked, however, and these funds may quickly run out should heatwaves and floods become a more regular occurrence.

“Decades ago, we warned that if we continue to build our greenhouse gas emissions, you’d have record-breaking temperatures associated with that, heatwaves and wildfires, … historic storms making landfall along our coastlines, causing immense destruction,” said Horton.

“Every one of those projections has come to pass. … That doesn’t surprise the climate scientists. What does surprise us is the lack of preparedness. … We aren’t particularly resilient to what Mother Nature will do to us.”

Watch this episode of Insight here. The programme airs on Thursdays at 9pm.

.jpg?itok=R5pc4Fwr)