Bad at Mother Tongue? What some parents are doing to help young ones be more fluent

Will children be more proficient in Mother Tongue if they start young? Is it all about scoring in the exams? The programme Talking Point looks at what might help make the learning more effective.

Young children at a Mandarin storytelling session.

SINGAPORE: When Talking Point host Steven Chia recently engaged in a session of Mandarin storytelling, the class barely looked attentive, let alone able to understand him.

Its participants were aged 18 months or younger and mostly could not speak yet.

But at about S$200 a month, the point of this enrichment programme, run by Hua Language Centre, is to expose young children to the language, never mind that they can hardly respond or sit still.

Since its inception in 2015, bar a halt during the pandemic, demand for the playgroup has increased, according to the centre. Its weekend classes are now full, and it aims to open more time slots after October.

Today, more than 180 enrichment centres in Singapore offer a Mother Tongue; sign-up rates at some of them have grown by up to 76 per cent over the past three to five years.

A quick Google search revealed that Mother Tongue enrichment classes, including Malay and Tamil, start for children as young as one to three years old.

Are they really learning? Should they start this young? “It’s hard to imagine,” said Chia as he set about discovering the effectiveness of Mother Tongue acquisition at a young age and how parents can otherwise help them be more fluent.

LACK OF EXPOSURE AT HOME

It turns out that there are benefits to starting young. According to National Institute of Education (NIE) research scientist Sabrina Sun He, children are picking up new words and learning basic grammar in these classes.

“Whenever you give children some language input, actually, they’re trying to detect the pattern from the input,” she said. While they cannot speak or write yet, “implicitly, they’re learning very well”.

Research has shown that children who are past nine months gradually lose the ability to distinguish foreign sounds, said Sun. This means a later exposure to a Mother Tongue makes it harder to identify its different units of speech.

While there are some who argue that the loss begins at the age of four, or even puberty, the message is that language acquisition at a young age makes it easier to “attain the native-like pronunciation and grammar”, she said.

The problem is that people are speaking less of their Mother Tongue at home.

Singapore’s population census in 2020 showed that in the ethnic Chinese group, English overtook Mandarin as the language spoken most frequently among 47.6 per cent of residents aged five years and over, up from 32.6 per cent in 2010.

For Mandarin, it fell to 40.2 per cent, down from 47.7 per cent.

Among ethnic Malays, a majority still spoke Malay most frequently. But at 60.7 per cent, this was lower than the 82.7 per cent recorded in 2010.

The proportion who used English most frequently rose to 39 per cent, compared with 17 per cent previously.

In the ethnic Indian group, 59.2 per cent spoke English most frequently, up from 41.6 per cent.

The use of English at home was generally more common among the younger population than older residents, the Department of Statistics said.

WATCH: Singapore’s Mother Tongue struggle — how bilingual are we? (22:13)

WHAT SCHOOLS CAN DO

To help with the situation, “one of the most important things” schools can do is promote the joy of learning Mother Tongues, said Ministry of Education deputy director-general Sng Chern Wei, who oversees general curriculum planning for schools.

“Once the kid enjoys the learning of the language, even if the home environment … doesn’t create many opportunities for him or her to use it, he or she may end up engaging in it on his or her own,” he said.

To this end, there is a Mother Tongue Language Fortnight to promote the use of Mother Tongues through special activities. For example, schools may invite writers or pop singers to engage with students.

Schools also encourage language learning beyond the classroom through interactive digital materials, such as language games and speech evaluation applications that can grade students’ fluency when they read a text.

Sng acknowledged that without the “social environment” for students to use their Mother Tongue frequently in their daily lives, they would not feel very confident or be fluent in the language.

That is why, in daily lessons, teachers also talk about popular culture and current affairs so that “the learning of Mother Tongues is closely tied to (students’) daily lives and (their) need to understand the modern world”, he said.

For many students, however, the need to score well might supersede interest in the language.

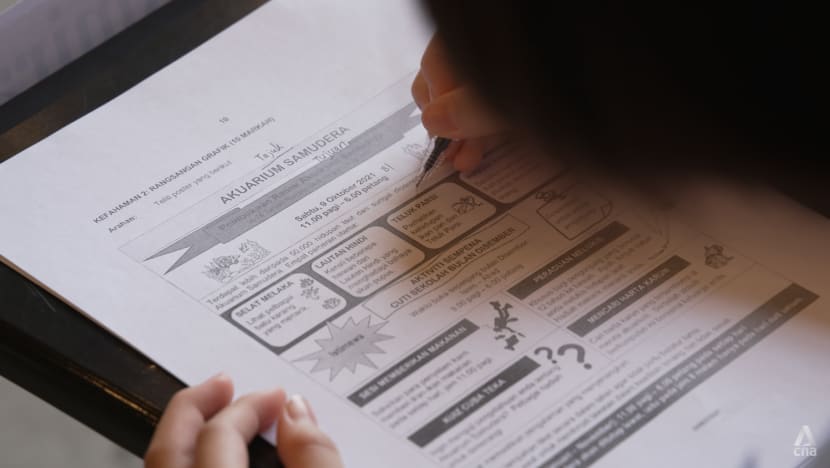

Private tutor Elmi Zulkarnain Osman said he has helped more than half his students score an Achievement Level 1 or 2 in Malay, but it does not necessarily mean they are bilingual.

He also cited students who had achieved an A1 in their O-Levels but lost their proficiency a few years later because they did not have the chance to practise the language.

Parents of students who come through his door put an emphasis on “scoring”, he said. “Although my personal task is to make sure that they love the language … at the end of the day, their grades matter.”

‘LANGUAGE IQ’ IS A FACTOR

While early exposure to language may mean a “higher chance” of better language acquisition, said Sun, another important factor in learning a Mother Tongue is language aptitude, or “language IQ”.

Memory, phonetic decoding and analytical reasoning ability will influence the speed of picking up a new language, and most experts think “you can’t really change it (or) train it”, she said.

According to her research, pronunciation and grammar are influenced more by language aptitude, while vocabulary can be influenced more by the environment.

Still, language learning is “complex”, she added. How much one’s parents use a language at home, how well they speak it, how often children use it with their parents and other family members, and how motivated they are to learn, play vital roles.

Sng noted that while there are more dominantly English-speaking households, the 2020 census also found that a second language is spoken in most homes. It is “really helpful”, he said, to “consciously create” a bilingual home environment for children.

If parents are “not so comfortable” using their Mother Tongue, he suggested they could make available Mother Tongue language books and encourage their children to watch Mother Tongue television programmes or listen to songs in their Mother Tongue.

Parents who attempt to use and become better at their Mother Tongue would also be an “inspiring” example to their children, he said.

Watch this episode of Talking Point here. The programme airs on Channel 5 every Thursday at 9.30pm.

Editor’s note: This article has been edited to accurately state that the census data refer to the proportion of residents aged five years and over, instead of the proportion of households/homes.