A Philippine tribe is fighting to protect their land. The ripples could affect us all

Few know a tribe on Boracay was evicted to make way for tourism. Could a road through the forest do the same to the Dumagat people living in another part of the Philippines?

Jefferey V Natvidad, one of the emerging leaders of the Dumagat tribe in Dibut, a village in Aurora province. (Photos: Christy Yip/CNA)

AURORA, Philippines: Riding in a motorcycle sidecar with a mere wooden plank for a seat, I held on for dear life with one hand while the other captured the tumultuous 90-minute journey on camera.

This was my grand introduction to the sleepy coastal village of Dibut, north of Metro Manila.

Although balancing on the kolong kolong was a workout for me, the passage through the villagers’ ancestral forest is a vast improvement on the past, when they had to traverse mountainous paths or seas that were stormy for half the year.

Almost too vast, some in the community might say.

Over 900 residents live here. Most of them are the first settlers of the land, known as the Dumagat. In 2015, they requested the reconstruction of a logging road from the 1970s so that they could transport goods easily by kolong kolong for sale in neighbouring towns.

It brought progress to the village but also a dilemma.

“On the positive side, people can travel conveniently. But on the negative side, this road is accessible to anyone,” said Marilyn F Dela Torre, 33, one of the tribe’s emerging leaders. “(The community) is influenced by the outside thinking, outside lifestyle … to gain profit immediately.”

The days of the Dumagat taking only what they need from the forest and the sea and sharing everything they have with their neighbours — a cornerstone of their culture — are slipping away, said chieftain Cipriano F Dela Torre, 58, who is Marilyn’s uncle.

Then as if the change was not enough, tractors reappeared in 2021 on untouched ancestral land, heralding a 65-kilometre national road that will connect three towns and go through Dibut.

The road is part of the “Build, Build, Build” programme, a key project of the previous Duterte administration. The Department of Public Works and Highways, which commissioned the latest construction, told CNA Insider the road will “open remote areas to economic opportunities” and provide “efficient, safe and faster transport”.

But the community was not consulted before the digging began and has not agreed to this new road, said Marilyn.

The tribe’s way of life may be far removed from that of city dwellers, but this dilemma between development and the preservation of indigenous culture and resources has profound ripple effects: Climate change experts have held up indigenous people as the last line of defence for the world’s forest cover.

In the case of the Dumagat, their leaders said they are doing everything they can to stop the national road. As at June, the excavation for the road’s entrance had started but not yet expanded into the mountains.

“What we want people to know is the importance of this land,” said Marilyn. “In the life of indigenous communities, everything’s connected … (It) is connected to the sea, connected to the forest. That’s the reason why we still exist — because of the resources here.

“That’s the connection we want to keep.”

TOURISM BOOM OR LAND GRAB?

Since the old logging road was reconstructed, among the people passing through Dibut have been tourists. And before the pandemic, municipal tourism officers turned up, wanting to train villagers to become tour guides, said Marilyn.

But mention tourism to Cipriano, and he will warn about the fate of the Ati people from Boracay island.

While the resort island’s White Beach often ranks among the worlds’ best, few travellers know about the tribe that had to relocate to the hinterland after the government pushed for extensive tourism on the island in the 1970s.

Will the Dumagat suffer a similar fate?

It is easy enough to see the tourism potential of this hidden gem that is their ancestral land: Clear waters and a sandy bay lined with palm trees greet visitors the moment they set foot in Dibut; lush forest everywhere forms a scenic backdrop while also keeping the district cool.

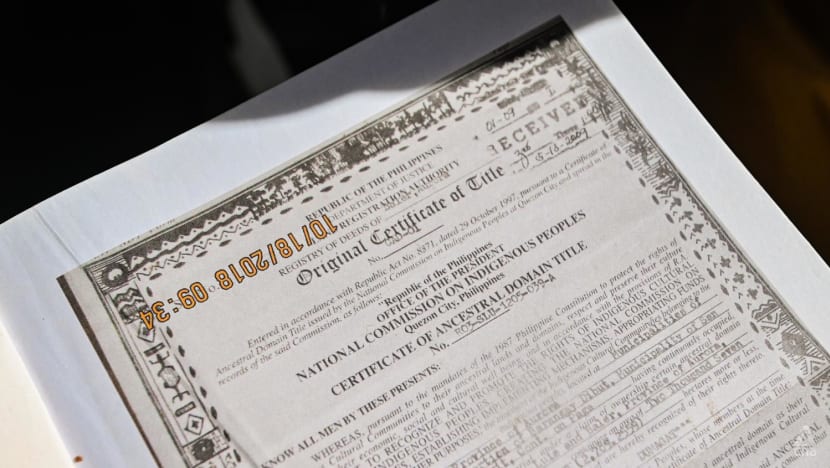

What the Dumagat have that the Ati did not is a law that came about in 1997: The Indigenous Peoples Rights Act. It protects ancestral domains such as the approximate 6,000 hectares — about 8,400 football fields — the Dumagat legally own.

Cipriano said he secured the tribe’s legal title in 2009, after 11 years of work.

To his dismay, however, some members found a way to sell their land rights to “make a quick buck” after the reconstructed road brought more people to Dibut and businesses started to show interest in the land.

“The landowners think they might get something like 100,000 (to) 200,000 pesos (S$2,480 to S$4,960). But do they know how to manage that kind of money? They don’t even know how to work for a living,” he said in Filipino.

“I’ve told (the tribe) many times: We might suffer the same plight (as that of the Ati). That’s likely to happen … The only soil they’ll ever own is the mud on their feet.”

But with their natural resources less abundant than before and with money in tourism, some of the villagers want a change.

Indeed, only “a few”, such as the tribal leaders, care to fight for their ancestral domain, noted Marilyn.

It is for this reason, however, that she works as a researcher at Daluhay, a local environmental non-governmental organisation. She is trying to raise awareness and encourage the tribe to advocate for their rights.

PROGRESS, ON THEIR OWN TERMS

Marilyn is the first Dumagat woman to graduate from university. So, it is not that the leaders oppose progress, she said. “We just want to do it in a more regulated and proper way.

Because the land’s owned by the indigenous peoples, the progress should be for them … They should be the ones who manage (the businesses).”

And in her view, the community is “not ready to transition their livelihood to tourism”. They need time to learn how to run a hotel or cater food for tourists, she said.

She also thinks there should be plans to control footfall, so that sacred grounds are not damaged, and to manage waste properly. The authorities do not seem to have considered the full impact of greater numbers of visitors, she said.

Under the 1997 Act, the Dumagat can say no to the proposed national road. The law provides for indigenous peoples’ right to free, prior and informed consent to any project or policy that will affect them. They also have a right to decide their developmental priorities.

But in practice, due process was not followed, especially as there was no consultation with the tribe, said Cipriano, who is now the indigenous peoples’ representative in the municipal government.

He learnt of the national road only after seeing part of the existing one-lane road being expanded, with the latter works officially due to be completed by January.

The tribal council filed a complaint with the Department of Public Works and Highways, which only then approached the council and the community, said Marilyn.

Responding to CNA Insider’s queries, the department said it introduced the community to the project through a series of meetings but did not indicate any dates.

The Dumagat found out that the project would also carve a new path from a neighbouring town, Baler, through the mountains to connect with the current road, then lead to the next town, Dingalan.

The two-lane carriageway from Baler — slated for completion by October — would be 4.5 km long and 6.7 metres wide, said the department.

It would cross sacred ground, where the tribal elders connect with the deities and which should not be disturbed, protested Cipriano, who called it “unjust”.

“Although we may be simple people, native people, we’re human beings who deserve respect,” he said. “(The state’s) utter disregard of our rights in our native land hurts us the most.”

The National Commission of Indigenous Peoples, the government agency responsible for protecting the rights of the country’s indigenous population, confirmed to CNA Insider that the Dumagat had not yet been consulted on the construction of the stretches of road in their ancestral domain.

“However, it must be noted that there are no constructions yet in barangay Dibut,” stated the commission, which acts as the middleman between indigenous peoples and other government agencies.

It said the highways department had applied to start the consent process in August 2020, but the request was not granted until this July owing to pandemic-related delays — which the department corroborated separately.

Yet, on the construction site of the road from Baler to Dibut, a notice said work started in March. Following a complaint from the indigenous people, the commission said it wrote to the highways department to “stop the road construction” until proper consultation has been conducted.

The department said it would not violate indigenous rights “on purpose” and has met the commission to “rectify mishaps that have occurred”.

THE ‘MOST EFFECTIVE STEWARDS’ OF THE LAND

Fierce indigenous protection of ancestral land and waters, and the resources within, is why some experts have highlighted local communities’ role in the fight against global warming.

Without acknowledging and protecting them, the goals set out in the Paris Agreement to limit temperature rise this century to 1.5 degrees Celsius cannot be reached, stated a report in March authored by the World Resources Institute, a non-profit organisation, and think-tank Climate Focus.

Half the world’s land is held by indigenous peoples and other communities, yet only 10 per cent is legally recognised as such, according to estimates from the World Resources Institute.

There is “abundant evidence that indigenous peoples and local communities are among the most effective stewards and protectors of forest lands”, stated the report released by a civil society-led effort called the Forest Declaration Assessment.

It examined how they impacted national climate commitments in Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and Peru. On average, indigenous and community lands were more than twice as effective as other lands in absorbing carbon, the study found.

Another recent study published in the Nature Sustainability journal found that in the tropics, the rates of deforestation and degradation in indigenous lands were lower than in non-protected areas.

Indigenous peoples’ traditional practices run “parallel” with climate change mitigation efforts, said Marilyn.

“If the government and other agencies want to promote conservation, it’d be best to harmonise (their efforts) with the traditional practices and concerns of the indigenous peoples.”

THE DUMAGAT WAY OF LIFE

Traditionally, the Dumagat have strived to preserve ecological harmony because the forest has given them what they needed. “Meat, medicine, everything,” cited Cipriano. “Mother Nature is important to us. It’s like our supermarket.”

And whenever they wanted seafood, they ventured just beyond the shore — no need to head out to deep waters, he added.

They were also careful to take just enough for the day and share any big catch among the community. “When they caught a wild boar, they’d divide it and send it to different homes … Nothing was sold. Everyone was given part of the catch,” he said.

“Now, one must sell to make a living because everything is expensive.”

The villagers grow subsistence crops, like banana, coconut, corn and sweet potato. They use only a small, designated zone for planting in order not to degrade the forest — a lesson passed down from their ancestors, he said.

And besides the medicinal herbs they still source from the forest to treat wounds, its native red and white Lauan trees provide villagers such as Jefferey V Natvidad with wood to build houses.

“The land, for me, is my life. Everything I need is here,” said Jefferey, 35, a tribal council member and the chairman of an indigenous voluntary organisation of forest guards in Aurora province.

He is so used to living off the land that when our entourage needed to fit into his boat to see the tribe’s fishing grounds, he built an additional bench from wood from the forest some days before our arrival.

A life dependent on nature is a reason the tribal council now hopes to restore areas that have been deforested following rampant illegal logging from decades past, which made wildlife scarce.

To this end, Daluhay and the Forest Conservation Fund — the organisations that arranged the trip to Dibut for CNA Insider, along with The Washington Post — have partnered to plant native trees in 400 hectares of degraded land in the Dumagat’s ancestral forest. This is equivalent to 560 football fields.

The organisations are also training more tribe members to be forest guards who monitor and report any illegal activities to the authorities, as well as training tribal council members in conservation governance, which seeks a balance between the requirements of human and economic development and those of biodiversity conservation.

Not-for-profit foundation Forest Conservation Fund aims to empower local communities in their conservation efforts through private sector donations.

Perhaps the most important project to Marilyn is the effort to document sightings of the endangered North Philippine hawk-eagle in her ancestral land as further evidence of the area’s conservation value.

“This research is our last hope … to prevent the construction of the road,” she said. “If we’re able to find any endangered species in the area that they’re going to destroy, then it could help us.”

As we made our way out of Dibut after our visit, Marilyn stopped us in our tracks and had us on our feet — what looked like a North Philippine hawk-eagle was perched on a tree. The last time Jefferey saw one was when he was a teenager.

These majestic birds, found mainly in northern Philippines, number only 400 to 600 mature individuals, according to BirdLife International’s assessment in 2016.

%202.JPG?itok=yFdjtCxQ)

‘SLOWLY, BUT SURELY’

Returning to Manila, where there were flush toilets and a Jollibee outlet every couple of blocks, I began to feel far removed from the life I had witnessed in Dibut.

While battling city traffic on my way to the airport, I asked my driver, Lorence, what he knew about indigenous peoples and the Build, Build, Build programme.

His reply was diplomatic but telling: “(Indigenous peoples) have simple lives. But change is the only permanence in this world, so whether you like it or not, it’s happening.”

Although he is not familiar with Dibut or the Dumagat, he is aware of the history of land grabbing in Boracay. He is confident that the new administration of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr, whom he supports, will address the native people’s concerns.

“For them to get better pay, to have a better life ... to have some opportunities to become successful, that’s the Build, Build, Build project,” he said.

This is not a strange sentiment to some of Dibut’s younger residents, Marilyn and Jefferey shared. Many among them want to work or study in the city.

Jefferey himself hopes that his three children, aged nine, eight and six, will attend college and that the young people of his district will pursue their ambitions.

But he also hopes they never forget where they came from or the need to protect their land and culture.

There is no life without healthy forests and oceans, believes Jefferey. “I choose to stay here and fight hard for our land because this is where I saw the (beauty of the) world.”

A month after my trip, I received an update from Marilyn. The Department of Public Works and Highways has started consultations with the community.

She is still hopeful the project can be stopped. But if the national road must be built, the tribe wants an alternative route that does not cut across sacred ground, and to see that waste and land is properly managed during the construction process.

Will this small tribe succeed in protecting their traditions and the Philippines’ forest cover? I think about what my kolong kolong driver said when I asked how long our ride would take: “Slowly, but surely.”