They left their home comforts as teens to study in Singapore. A scholarship wasn’t the only reason

Secondary school and pre-university students arriving here on scholarships have diverse expectations, from the non-academic to the doors they think Singapore will open. The outcome is not always what they had in mind.

Some of the international scholars at Hwa Chong Institution Boarding School a few years ago. (Photo courtesy of Yap Kian Yew)

SINGAPORE: While in secondary school in Hanoi, Le Minh Giang used to have little respite on school days. Once school ended at 4pm, he had to prepare for cram classes in the evening.

But these classes were not related to what he was learning in school; instead, they were tailored to prepare him for the opportunity to study in Singapore — through a shot at a scholarship.

Every year, the Ministry of Education awards a variety of bond-free scholarships to students from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), China and India, who join Secondary 1, Secondary 3 or Pre-university 1 classes in selected Singaporean schools.

The scholarships cover an annual allowance, hostel accommodation, return airfare and school fees. For students like Giang, extra preparatory classes are a small price to pay for a scholarship they covet.

The selection process is rigorous and competitive: Shortlisted applicants are required to take a series of English, mathematics and general logic tests. A small number are then invited to the final stage of selection, an interview.

Vedant Sandhu, 22, recalls that he was one of three recipients of the Singapore Airlines Youth scholarship for Indian students in the year he applied, out of thousands of applicants.

These international scholarship holders make up 0.9 per cent of Singapore’s secondary school and pre-university students, the ministry reported in 2019.

Though in some schools, their numbers are more sizeable. Giang, who received the Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*Star) scholarship in 2015, says he had 31 fellow recipients in his batch in Anglo-Chinese School (Independent).

It may be little wonder that they are attracted to Singapore’s educational system. But the idea of studying here also holds different promises for different scholarship holders, who have an array of journeys and dreams. And not all expectations are realised eventually.

GOING THE EXTRA MILE FOR A SCHOLARSHIP

For 21-year-old Giang, the seeds of his “dream” of studying in Singapore were planted when his older brother, Le Minh Phuc, was awarded Singapore’s Asean scholarship in 2010.

“Before my brother went to Singapore, I didn’t even know it was possible to study abroad before university,” he recalls.

Phuc was placed in National Junior College. Through weekly video calls on Facebook Messenger, he relayed details of his overseas school trips and Malay dance co-curricular activity sessions.

To Giang, these represented an escape from the “long days of classes after classes” at his secondary school in Vietnam. He was motivated to follow in his brother’s footsteps.

“I felt that (Singapore’s) was a more holistic education that (would give) me more freedom to do what I want,” he says.

But first, there was cram school to attend, to increase his chances of getting the scholarship. He started lessons in Secondary 1 and learnt material from Singapore’s education syllabus.

The scholarship’s popularity has spawned a boutique industry not just in Vietnam.

Upon returning home after his A levels, scholarship recipient Albert Augustino from Medan, Indonesia, set up a tuition centre — along with three friends — to prepare students for the selection process for Singapore-based scholarships.

It provides lessons in English, mathematics and interview preparation. Despite competing with a larger, more established tuition centre, it signed up 12 students within a few weeks. Tuition centres for these scholarships are “widespread”, says the 20-year-old.

Scholarship recipients from Malaysia and Thailand also affirm that “large communities” of parents and students are formed around these tuition centres.

After submitting his Secondary 3 scholarship application, Giang underwent two days of assessments. Following the final interview, he was informed that he had been awarded the A*Star scholarship, along with nine others.

“When I got it, I was quite speechless (with) that feeling that you (have got) something you’ve been working so long towards,” he recalls.

My parents were really happy because they’d spent a lot of effort and resources on me going for this scholarship.”

While his path to a scholarship was relatively straightforward, it was less so for 22-year-old Presca Lim.

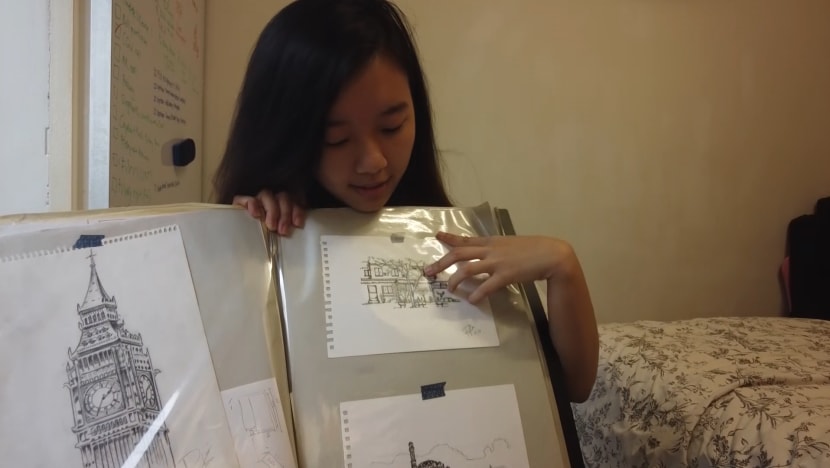

Born in Penang, Malaysia, she spent her childhood drawing on any surface she could get her hands on. “Everything I did was about art,” she recalls.

In Primary 6, the topic of her future profession came up in a conversation with a teacher.

“I said I wanted to be an artist, then she said why not be an architect? It’s more professional, and you earn more money,” Lim recounts.

“I thought: Oh, that sounds cool. When I told my family and friends, everyone supported this idea. And that’s how I decided that should be my dream.”

She came up a plan: Study in Singapore first, for the opportunities that would “equip (her) better” to achieve her dream, and then go to Germany to study architecture. But it was easier said than done.

Her first application for the Asean scholarship in Secondary 1 was rejected, along with the second, third and fourth. She had been “just trying (her) luck”, she acknowledged.

“I needed to get my life straight,” says Lim, who was in Secondary 3 by then.

To ensure that her fifth application would be her final one, she practised on workbooks from Singapore and applied for a school-based scholarship available to certain schools in Malaysia affiliated to Methodist Girls' School in Singapore.

“When I finally got the scholarship, I was excited and hopeful. It was like a promising future,” she says.

PASSION MADE POSSIBLE

Once in Singapore, change comes for these scholarship holders in both expected and unexpected ways.

Here, school usually ended by 2pm for Giang, and he was excited to use his new-found time to explore non-academic pursuits, like his fledgling interest in dance, which he could not fully pursue in Vietnam owing to his busy schedule.

One of the first things he did in Singapore was take up dance as a co-curricular activity.

He still remembers every detail of his first dance class at O School, a dance studio at *Scape — from the lyrics to the steps.

“I was very awkward. I didn’t know what was normal in a dance class, and the whole lesson was (about) me struggling to follow hip-hop,” he says. “But after that, I was excited to learn more.”

Dance soon became an abiding passion as he participated in dance auditions and competitions. In this way, he was able to enter Victoria Junior College via the Direct School Admission (DSA).

Today, he is heavily involved in the Singapore dance scene and has even judged competitions, a role taken on by the more experienced dancers in the community.

Would things have been different if he had stayed in Vietnam? “I wouldn’t be doing the same style of dance I’m doing today. And I wouldn’t have met my closest friends,” he replies.

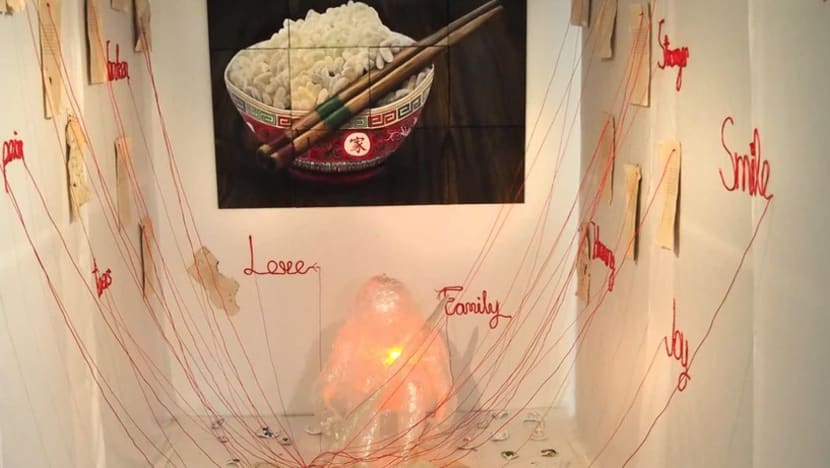

For Lim, who arrived in Singapore expecting to study a predetermined set of subjects, her initial dream of becoming an artist resurfaced unexpectedly in her first week of school: An art teacher informed her that it was possible to take Art as an O-level subject if she submitted a portfolio.

“Back in Malaysia, art wasn’t the most important subject at school. But when I found out Singapore’s O levels deemed art as a very legit subject, that gave me hope,” she says.

She passed the aptitude test and enrolled in her school’s Art Elective Programme — for the first time, she could pursue art in a well-funded environment. It soon became “one of the things that got (her) through (her) stay in Singapore”.

She excelled in the subject, which allowed her to enter Hwa Chong Institution (Junior College) via the DSA scheme.

Eventually, she enrolled at the Singapore University of Technology and Design, hoping to study architecture and sustainable design before planning her route to Germany. After a chance experience with a computer science course that she liked, however, she switched courses.

“I changed my 10-year ambition in a few months,” she remarks. She now aspires to be a UI/UX (user interaction and experience) designer, to combine her love of both computer science and art.

SCHOLARSHIP BLUES

While scholarship recipients like Giang and Lim have flourished under Singapore’s educational system, not all of them manage to adapt well. Some of them have had their scholarships terminated for poor academic performance or disciplinary infractions.

WATCH: Life as an international scholar in Singapore (10:32)

Take, for example, Yap Kian Yew, who was invited for the scholarship selection test and interview in 2013 after he was placed fourth in the Asia-Pacific Mathematical Olympiad for Primary Schools.

At the age of 13, he was placed in the Integrated Programme at Hwa Chong Institution along with other scholarship recipients who had done similarly well in the competition.

The decision to accept the scholarship was automatic, yet he “wasn’t exactly sure of what to expect”. The 21-year-old says: “(It’s) almost like I decided to come on a whim.”

The academic transition proved difficult for the straight-A student from Malaysia. He “didn’t know how to react” when he got Cs in his first few tests.

“It was a bit of a shock because of the difference in difficulty,” he recalls. “I wasn’t used to working hard … You have to be quite independent (in Singapore), and I wasn’t able to do that.”

The school arranged to meet his parents after his first semester. But without his parents’ full supervision, he started to spend more time on computer gaming, which led to his laptop being confiscated in his second semester.

“On weekends, I spent 18 hours (a day) gaming. I’d game into the night, go for breakfast, then sleep,” he recounts. “I lost my passion for learning. Instead of trying to catch up, I just gave up.”

Hours after school were spent sleeping in various places in his student dormitory, and his grades failed to improve.

While he periodically failed subjects, he was able to pull his grades up to the minimum needed for promotion in the year-end exams. Eventually, he dropped out of the Integrated Programme and was placed on the O-level track.

Paradoxically, he continued to perform well in maths Olympiads. He remembers getting the F9 grade in a Secondary 2 math paper and receiving a gold award in the Singapore Math Olympiad on the same day.

“There was a disconnect between what I was good at and what I did in class,” he says.

‘I DON’T REGRET COMING’

Every semester, international scholarship recipients with poor academic results are placed on a warning list of sorts, which entails a visit from ministry officers. Yap found himself on the list regularly.

To change his behaviour, a staff member in charge of managing scholarship recipients asked Yap’s peers to keep tabs on his movements throughout the day.

“I saw photos of me sleeping on the sofa in the common area. They had a whole document of what I was doing at different times of the day, and they showed it to me and my parents,” he recalls.

“My mum was pretty angry. They didn’t try to connect with me on a personal level.”

Part of his apathy stemmed from his deteriorating mental health, and his lowest point came in Secondary 3. “I didn’t want to go to school. I’d lie in bed and not go,” he says.

He was referred to a school counsellor and eventually was diagnosed with mild depression.

When he took a month’s break from his studies to return home, his relationship with his school had deteriorated to the point where he told his parents to “expect (his) scholarship to be terminated soon”.

Having got into trouble for several absences from school and continued academic under-performance, the writing was on the wall. Six months before his O levels, he received an email informing him that his scholarship had been terminated.

“At that point, I felt ‘whatever’. I just wanted to finish my O levels and get out,” he says.

As he did not initiate the termination, he did not have to pay a financial penalty, a fear many scholarship recipients have. He was able to continue studying but had to start paying school fees out of his own pocket.

His L1R5 score of 11 in his O levels qualified him for junior college in Singapore, but he returned home and took his A-levels at Methodist College Kuala Lumpur. He is now studying computer science at Monash University Malaysia.

“I don’t regret coming (to Singapore) as I learned a lot. But I feel I’d have developed better if I hadn’t come,” he says, referring to his struggles to adapt.

While his story illuminates how there can be a mismatch between expectations and ability, terminations remain rare. He was the only scholarship recipient in his batch of 11 whose scholarship was terminated.

For the hopeful applicants scattered throughout the region, Yap’s story may be a cautionary tale but not a deterrent.

Asean scholarship recipient Hnin Azali believes its benefits outweigh the costs of living independently at a much younger age than her peers. That is why the 21-year-old convinced her younger sister in Mandalay, Myanmar, to also apply for the scholarship.

The Vietnamese students attending cram school as Giang did may feel the same way, though a Singapore scholarship might capture each child’s imagination differently, in stories yet to unfold.