‘Killing your own semiconductor business’: How will US ban on chip exports to China play out?

The US cites national security reasons for its export controls on advanced chips and equipment. But these moves could be self-destructive as China is the world’s largest semiconductor consumer, Chinese experts tell the programme Insight.

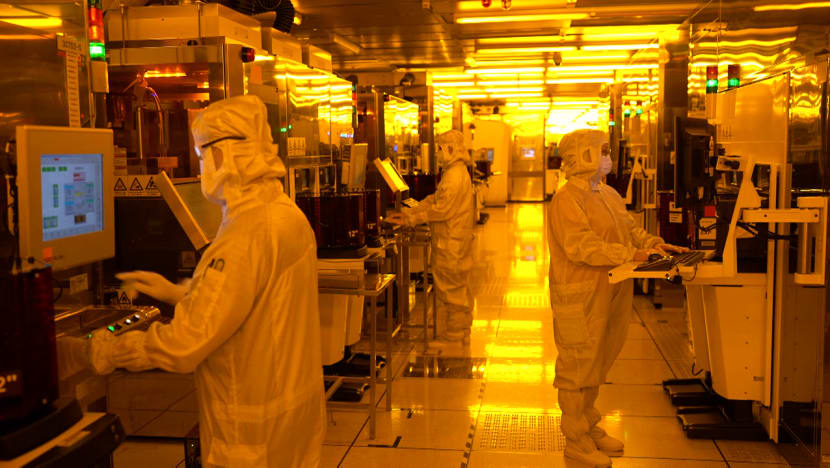

China consumes over half of the world’s chips as a global manufacturing hub, but US companies are market leaders in chip activities that are most research-intensive.

SHENZHEN: Ever since the United States announced export controls in October to cut off China’s access to advanced chips and semiconductor manufacturing equipment, Shenzhen businessman Tom Zhang has found it harder to source and distribute chips.

Stocks that his company, Smart Jade, were previously able to import from the US to sell to technology companies in China have become difficult to buy.

The way he sees it, the chips war is simply the US “looking for excuses” to suppress China. “The top dog doesn’t want to give up his seat to the number two,” said Zhang, Smart Jade’s chief executive officer.

The US is also getting its allies on board. In January, the Netherlands and Japan were reported to be joining in the restrictions on exports of semiconductor manufacturing equipment to China, but details are presently scant.

Meanwhile, China has launched a trade dispute in the World Trade Organisation over the US’ export controls.

Will the US choke off China’s rise in artificial intelligence (AI), supercomputing as well as its AI-related military advancements? Or will it supercharge Beijing’s bid to be a technological superpower?

The programme Insight examines a face-off that could have far-reaching implications for Asia, which manufactures the bulk of the world’s microchips.

WHY SEMICONDUCTORS MATTER

Chips are “absolutely necessary” for almost everything we use in our daily lives, such as smartphones and vacuum cleaners, said Ryu Yongwook, an assistant professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, who specialises in international relations.

A chip, also called a microchip, is a set of electronic circuits on a small piece of silicon, according to Dutch firm ASML, which makes lithography or projection systems that are essential to chipmaking.

WATCH: US’ chip war on China — will China win or lose the tech race? (47:44)

Transistors on a chip act as miniature electrical switches that can turn a current on or off, and a chip the size of a fingernail contains billions of transistors, ASML said on its website.

The US is not concerned about chips that go into appliances like rice cookers and calculators, said Ryu.

“But when it comes to the latest military equipment, the latest radar systems … artificial intelligence (and) quantum computing — stuff that’s necessary for the most advanced digital economy — the USA wants to curtail China’s development.”

The US’ rationale for its exports controls is national security.

To justify its October regulations, it analysed the “connection” between exports of advanced chips and semiconductor technologies and the “military supercomputers that China uses to develop nuclear weapons and advanced nuclear missile delivery systems”, stated a report this month by the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, a policy research organisation in Washington.

The US Commerce Department and President Joe Biden’s national security adviser have indicated that China’s military-civil fusion is “speeding up”, economic and data policy analyst Jordan Shapiro with the Progressive Policy Institute in Washington told Insight.

Military-civil fusion refers to the two-way transfer of technology, resources and information between military and civilian entities.

“There’s more integration between the civilian and the military technology development, which is creating a little bit of a security and economic challenge for America,” she said.

Ryu reckoned that Chinese President Xi Jinping’s Made in China 2025 plan, announced in 2015, to achieve 70 per cent self-sufficiency in semiconductor production by 2025 “alarmed” the US government.

“The concern was not only China’s tech rise, but the pace at which China’s tech rise was taking place. And at the same time, the US-China strategic rivalry was intensifying,” he noted.

WHAT THE EXPORT CONTROLS ARE ABOUT

The US’ countermeasures have been broad. US companies are barred from supplying advanced chips and chipmaking equipment to China unless they receive a special licence. But licences would be mostly denied, the US authorities said.

Companies anywhere in the world will also be barred from selling chips used in AI and supercomputing in China if they are made with US technology and software, the New York Times reported.

US citizens and “resident aliens”, including green card holders, may not work on or support the production of advanced semiconductors for China.

Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said in October that the Biden administration’s move is “a very serious one” and could have “very wide ramifications”.

Ryu said: “The USA has identified a critical area that could hurt China badly. And the USA also knows that China doesn’t have many other options to respond to this.”

Currently, China consumes more than 50 per cent of global chips as the manufacturing hub of the world. But it manufactures only around 15 per cent of global output, he cited.

China lacks the capacity to manufacture advanced chips at 7 nanometres and below — a nanometre is one thousand millionth of a metre — and its reliance on imports from places like Taiwan and South Korea is “100 per cent”, added Ryu.

And although Asia — namely Taiwan, Japan, South Korea and China — manufactures over 70 per cent of the world’s chips, US companies are market leaders in activities that are most research-intensive, according to the US’ Semiconductor Industry Association.

These activities are electronic design automation and core intellectual property (72 per cent), chip design (49 per cent), and manufacturing equipment (42 per cent), according to the association’s 2022 State of the US Semiconductor Industry report.

Last August, the US also enacted the Chips and Science Act, allocating US$52.7 billion (S$70 billion) over five years for semiconductor research, development, manufacturing and workforce development in the country.

WHAT WILL CHINA DO?

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin has called the US’ moves an attempt to impose a “technological blockade” on his country.

China has also condemned the provision in the US’ Chips Act that prevents American tech companies that receive funding from expanding their advanced chip manufacturing in China for 10 years.

“It’s very unfortunate to see the US now becoming protectionist and starting this trade war (under) the Trump administration (and the chip war under) the Biden administration,” said Wang Huiyao, the founder and president of think-tank Centre for China and Globalisation.

The US, as a “champion of free trade”, has lost “moral ground” with its chip policies, which include sanctions on Chinese firms, he charged.

China’s chip purchases, meanwhile, have enabled Taiwanese and South Korean companies “selling at the doorsteps of China” to become the largest in the world, Wang added.

“By trying to kill China as the largest buyer of chips products … you’re killing your own semiconductor business,” said Wang’s colleague Victor Gao, vice-president of the Centre for China and Globalisation.

Some commentators have also said the US’ restrictions have created unease among its allies.

Gao said: “If you really talk to the Dutch decision-makers and, to some extent, the Japanese decision-makers, they don’t want to go along with the maximum pressure from the US.

Why? Because the only way to … grow their semiconductor businesses … is to work closely with their largest customer, that is China. How can anyone in the world truly believe they can maximise their own benefit by killing their largest customer?”

As for military-civil fusion, he thinks Chinese companies are “doing what they’re supposed to do”. He said: “In the philosophical sense, everything you produce can be used by either the civilian side … or by the military side of the equation.”

Some pessimistic reports project that the ban could set China’s tech industry back by decades. But there are analysts and industry players who believe China will close the technological gap in the longer term and become self-sufficient in semiconductors.

In December, Reuters cited three sources who said China was working on a support package worth more than 1 trillion yuan (S$193 billion) to boost chips production and research.

The “short-term difficulties” created by the US’ chip ban will “motivate us to fight”, said Song Lijun, the CEO of Shenzhen Winsemi Microelectronics.

The US’ “irrational” actions will also galvanise youths in China’s tech industry, said Hong Kong University postgraduate AI student Gao Yuxun, 23, who is from Xi’an.

“An increasing number of youngsters are entering this research field. They’ll help us break the tech barrier.”

WHAT EFFECT ARE EXPORT CONTROLS ALREADY HAVING?

The impact of earlier curbs may offer clues about China’s current situation.

Since 2019, the US has imposed export controls on Chinese smartphone maker and tech firm Huawei Technologies, cutting off American companies’ supply of chips to Huawei and its access to US tools to design its own chips.

Last year, the sale of new equipment by Huawei (and some other Chinese firms) was also banned in the US.

“Huawei has been pretty much removed from the global smartphone market,” noted Ryu.

Huawei has since replaced more than 13,000 parts in its products that were hit by US sanctions, it reported this month.

Following the latest export controls, Apple halted plans to use chips from Yangtze Memory Technologies Co, a major Chinese chip supplier, in its iPhones, news outlet Nikkei Asia reported in October.

The Financial Times reported that revenues at the chipmaker and another large Chinese firm, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation, will suffer.

But costs could go up for Western manufacturers — and their customers — that use cheap chips from China.

Related stories:

The US has granted some exemptions, such as one-year licences to Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co and Samsung Electronics to continue ordering American chipmaking equipment for their facilities in China.

For companies dealing with less advanced microchips — such as Stats ChipPac in Singapore, a subsidiary of China’s JCET Group — it appears to be business as usual.

“The products we’re doing aren’t the super high-end (ones), like wafer processing or certain specific software that goes into the manufacturing or design process. I think that (US curbs) isn’t a concern,” said Stats ChipPac managing director Chiou Lid Jian.

“Furthermore, we have a sizeable customer base including Europe, the US, Japan, Taiwan.”

While there are longer-term risks if there is technological decoupling, the US and China are still in a semiconductor race for now, said Song. “We’re improving; the US is also improving.

“The gap’s narrowing, but when exactly can we catch up or even overtake? This is a good question.”

Watch this episode of Insight here. The programme airs on Thursdays at 9pm.