How fake news fanned the flames of war in Ukraine

Before Mr Donald Trump deployed the term, and before Russian trolls tried to influence the 2016 US elections, the problem of fake news began in the former Soviet state.

The conflict in eastern Ukraine has claimed over 10,000 lives. (Photo: Sega Volskii/AFP)

KYIV: It was late 2013, and protests had erupted in Kiev. Among other things, the protestors wanted closer ties with the European Union. What followed was Ukraine’s cautionary tale for the world, including South-East Asia, believes its Foreign Minister Pavlo Klimkin.

“It's about understanding Russian tactics or non-conventional war, which is very important for Europe, which is very important for the United States, but it’s, in the same way, very important for Asean,” he says.

“How can you be sure that Asean won’t be a target of these tactics, whether it’s Russia or maybe from somewhere else?”

READ: Disinformation campaigns can create 'true armed conflict': The Ukrainian experience with Russian propaganda

Before United States President Donald Trump deployed the term, and even before Russian trolls tried to influence the 2016 US elections, the problem of fake news began in Ukraine, with propaganda from its neighbour to the east.

Five years on and Ukrainians who are fighting back believe the disinformation tactics that brought conflict to their country have now spread to the rest of the world.

Indeed, living with disinformation has taken its toll in Ukraine and elsewhere, as Channel NewsAsia finds out in The Truth About Fake News, a special on who has been peddling falsehoods, the impact, and issues at the heart of the problem.

INFORMATION WAR

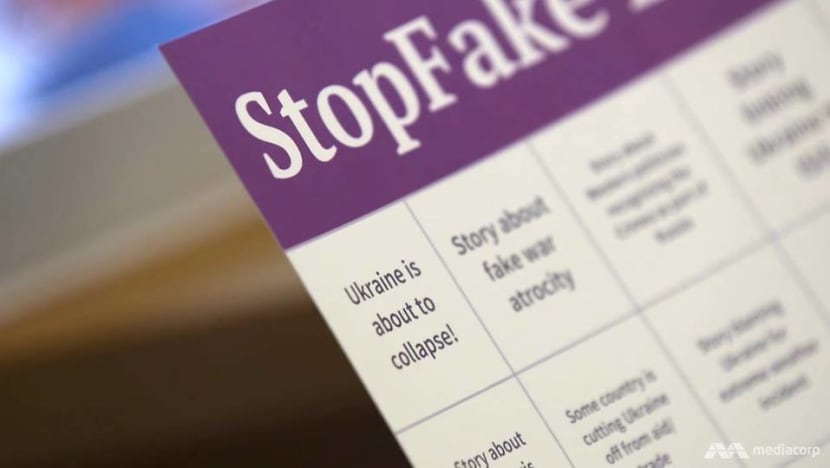

Since Ukraine’s crisis began, one organisation that has been trying to persuade people that fake news was not just a Ukrainian problem is the fact-checking group StopFake.org, which started in 2014.

And its testimony reached Singaporean shores in March, during the hearings of the parliamentary Select Committee on Deliberate Online Falsehoods.

“Our project proved that … Russian media disseminate not facts, not news, but propaganda,” StopFake co-founder Ruslan Deynychenko had said. “Unfortunately, this ignorance of this threat cost our country too much.”

In 2013, pro-EU Ukrainians were hoping for European integration, but any progress towards this would have meant a rejection of Russian influence – a “sensitive and painful” topic for the Kremlin, Ukraine’s Deputy Minister of Information Policy Dmytro Zolotukhin tells CNA.

Tensions began to flare in eastern Ukraine as Russian sympathisers rallied. Ukrainian authorities believed that Russian channels were painting a negative picture of Ukraine and Europe, creating divisions between the pro-Ukraine and pro-Kremlin camps.

“Ukrainian people are heading towards anti-Semitism or radicalism or so on and so forth,” cites Mr Zolotukhin. “The main agenda … was to ruin the will and ruin the hope of Ukrainians to integrate with the EU.”

One pro-Kremlin claim was that Ukraine’s ethnic Russians were being oppressed and attacked; for example, a video on Russian television supposedly showed the Ukrainian military firing on civilians, when the men filmed were actually Russian militia.

The Russian narratives worked. Crimea held a referendum to leave Ukraine and was annexed by Russia in March 2014. Within a month, separatists seized territory in eastern Ukraine’s Donbass region. The country was now at war.

“It was a clear information war. It was a war against us Ukrainians, it was a war against the whole of Europe and the Western world,” says Mr Klimkin.

READ: Commentary: Little resolution on Crimea, even as Ukraine moves out of Russia's embrace

StopFake is still on the front line of this war, keeping an eye on Russian narratives.

“Ukraine was one of the very first labs where they were testing all those narratives, and then they could easily … adapt them (for) use in any other country,” says StopFake.org chief editor Yevhen Fedchenko.

“Few people were paying attention to this. And then finally, everybody realised that, yes, Russia had grown that capacity and could use that capacity to influence not only public opinion in Ukraine, but public opinion in many other European countries.”

GROWING PROBLEM

In 2016, the problem had reached American shores, all the way from a building in Saint Petersburg, where Russian trolls from the Internet Research Agency (also known as Glavset) were creating fake news stories for the US elections.

Since then, the term “fake news” has been used very broadly and sometimes abused, notes Singapore’s Institute of Policy Studies senior research fellow Carol Soon.

“If we don't really understand what it is we’re tackling, then of course it’s very challenging … to prescribe the necessary measures.”

READ: 'Overly broad use' of fake news term 'problematic', say IPS researchers

Another difficulty is that “the term, in some ways, has lost its value”, according to Mr Damian Collins, the chairman of the British House of Commons’ Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee.

“Because it’s used generally, not least by Donald Trump, as a general descriptor of news that you don’t happen to like or agree with,” he explains.

But for those studying the problem, the term is more specific to the idea of disinformation.

Dr Soon says: “Disinformation is essentially the kind of problem that, I think, governments worldwide are more concerned with because it’s information that's produced deliberately to achieve a political or an economic agenda.”

And in Europe, the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (Nato) has seen foreign disinformation become a growing problem.

“We've seen Russians using the migration crisis, trying to target (German Chancellor Angela) Merkel. Brexit increasingly shows some elements of Russian interference,” cites Mr Janis Sarts, the director of the Nato Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence.

Last year, the Dutch intelligence services said Russia attempted to influence the Dutch election. And this year, the US finally charged 13 Russians and three Russian companies with interfering in the American political system.

“It's not surprising that Russia gets the most publicity because it has recently been caught red-handed,” says Mr Benjamin Ang, who leads the Cyber and Homeland Defence Programme of Singapore’s Centre of Excellence for National Security.

“But this is something that all major powers are involved in, whether it’s Russia or China or the US, and some of the smaller powers like Iran or North Korea.”

SECRETIVE MILITARY UNIT FIGHTS BACK

In Ukraine, the threat of fake news to national security goes beyond mere perception. And it has undermined the people’s sense of identity and belonging to their country, says Mr Sarts.

Now, in the country’s occupied eastern territories, Russian channels tell one story of the conflict, and the Ukrainian media tell another.

“The fact is that our people here don’t believe in the media. Neither do the people over there,” says Kremmina District Hospital head doctor Larysa Kulbach, who maintains contact with those in the occupied areas.

WATCH: Going to war over — and against — fake news (5:22)

Professor Ben O’Loughlin, the director of the New Political Communication Unit at Royal Holloway, University of London, got a sense of this impact of the misinformation campaigns when he spent a lot of the past year doing research in Ukraine.

“Although in the West, trust in the institutions has fallen, it's nothing as compared to in Ukraine,” he attests.

Mr Zolotukhin says Russia’s aim is to “share as many versions of reality” as it can – “about 30, 40 versions” in the case of the downing of Malaysia Airlines flight MH17 over eastern Ukraine.

“If everything’s possible, then none of the sources is reliable,” he adds. “You can’t make decisions on whether it’s true or not.”

While Ukraine has blocked Russian broadcasts since the conflict, this is hard to enforce near the border of the occupied lands, so the military is also taking its fight to the airwaves.

“We broadcast over radio space and drown out the transmissions of the enemy’s signal,” explains “Gonta”, a soldier who is part of a secretive unit given this task.

“Our goal is to actually give people an opportunity to hear and see Ukrainian radio and TV. We show them an alternative point of view.”

A new TV tower has been constructed, which allows the unit to transmit to the occupied regions, and Gonta thinks such efforts are paying off.

“People have begun to change their minds … about what's going on around them,” he says.

“They’ve begun to see things in a different way … think more critically and no longer simply believe what Russia imposes on them. I wouldn’t be here if I didn’t believe in this.”

THE LATVIAN EXPERIENCE

Ukraine is not the only former Soviet state where Russian channels are available, illegally or otherwise, and dividing the country.

In Latvia, journalist Inga Springe has, for over six years now, been looking at the kind of stories on Russian media aimed at the EU member state’s ethnic Russians, who form a quarter of its 1.9-million population.

“There are several messages. One is that Latvia’s a failed state, we’re fascists, we don’t need Nato and we don’t need the EU,” she says.

Many of the ethnic Russians live in economically depressed areas, and some of them believe that they have been marginalised. Mr Dmitry Prokopenko, a campaigner for Russian rights, is one of them.

“Purely according to statistics, for example, birth rates are lower among Russians. The rate of emigration is higher, and the mortality rates are higher. The level of crime is higher, and these are things you can’t argue with,” he contends.

“When the Russian people feel that the Latvian state treats them with hostility and discrimination, they’d naturally look for protection. And of course there are people who try to seek protection from Moscow because, again, it’s logical.”

Ms Springe agrees that Russian speakers in Latvia may not feel that they belong. “They feel as if they’re lost (and) no one cares about them,” she says. “That’s why many Russian-speaking people who live here are watching Kremlin channels.”

Things may change for them after the pro-Kremlin Harmony party topped Latvia's polls in October. But choosing to follow Russian media is a “major problem”, says translator and editor Ingmars Bisenieks, because of the “brutal lies” presented.

Latvia’s experience of disinformation campaigns was also the subject of one of the representations to the Select Committee in Singapore.

And committee member Edwin Tong says the hearings brought it home to the Select Committee that “these problems are real, they’re happening around the world, and they do have a significant impact on society”.

To fellow committee member Chia Yong Yong, it is clear that “in this day and age, you don’t need to fire a bullet to fight a war”.

“You just need to sow discord and distrust. And the best way to do that is through falsehoods,” she says.

Watch the two-part special The Truth About Fake News here.