His double life as a construction worker and a 'famous poet' in Singapore - and the price he paid

Basking in fame after his book was published, Mohd Mukul Hossine was increasingly unhappy with life as a migrant worker. But could he afford to ignore reality, with his parents depending on him? Part 3 of CNA Insider's Life After Singapore series.

Mohammed Mukul Hossine wrote a number of poems over the years, and got the help of Singaporean poet Cyril Wong to transcreate them in English. They were published in the book Me, Migrant in 2016, which made him an instant celebrity.

PATGRAM, Bangladesh: Mohammed Mukul Hossine’s passion for poetry began with a small transistor radio.

As a boy, home for his family of 10 was a small tin shed in the middle of a lush floodplain. In the fields around it, his father grew rice, jute or beans and potatoes, depending on the season, while the family’s milk goats and cows roamed freely.

Almost everyone in this county at the northern border of Bangladesh was – and still is – a farmer. Barely one in four could read or write. Little Mukul knew nothing about music and art.

So when his older brother passed him a small black radio and, for the first time, he heard Bengali folk songs playing on the local station, Mukul was shaken to his soul.

He stopped kicking balls or going to the river with his friends. Instead, the six-year-old would sit in the shade with his sister, listening and singing along to all his favourite songs.

Sometimes, when he got bored of singing the same lyrics, he would make up his own. And his sister would tell him: “Mukul, you’re not singing. You’re making poems.”

GOING TO SINGAPORE

The first time Mukul had a poem published in the school magazine, he was in Primary 4. He was a bright student, but being only interested in the arts – singing, drawing, writing – he did poorly in other subjects.

His parents were not pleased, but mostly they let him be. As their second-youngest child, Mukul was doted on.

Throughout primary and secondary school, Mukul was always performing on stage at school events. As he got older, he wanted to make singing his career. So he enrolled himself in an arts school.

But life as a college student came to an abrupt end seven months into the school year, when his father pulled him aside one day and presented the 18-year-old with a choice.

Mohammed Kapil Uddin had a friend who was earning good money in Singapore. Wanting to give one of his sons the same opportunity, Kapil had paid a job agent by selling a part of his farm. All that was left was to decide which of his sons to send – and as Kapil’s favourite child, Mukul was first in line.

In 2008, Mukul arrived in Singapore and became one of the few hundred thousand foreign construction workers on the island. No one had told him what working here actually meant.

“I thought by going there, I could carry on my passion for singing and writing,” the 29-year-old told CNA Insider. “That’s why I decided to go there.”

‘LIKE A PRISON’

Dr Tan Lai Yong first met Mukul in 2015 at a workers’ dormitory in Mandai.

A volunteer doctor at HealthServe, a non-profit organisation that provides medical care and counselling to migrant workers, the 58-year-old Singaporean was there to play sepak takraw and football with the workers, hoping to recruit some as volunteers for the clinic.

After the game, he asked the men what they did in their spare time. Most gave answers like playing cricket or watching movies. One response was unexpected: Writing poems. It came from Mukul.

“I said, ‘Oh, interesting',” Lai Yong recalled. He had not taken note of the young man dressed in a bright flowery t-shirt until this point. But the more he probed, the more intrigued he became. "He told me that he writes poetry on scraps of paper and cement packaging and so on."

By then, Mukul had been in construction for seven years, but he was still struggling to come to terms with being a labourer.

“When I first went to Singapore, I didn’t know that I would work as a construction worker and that I had to work hard,” Mukul said.

Singapore felt like a prison. Because I had to abide by many rules and regulations.

“I tried to adjust to the new environment, and tried to make myself like the people,” he added.

But it was evident that Mukul had issues that affected his performance at work.

In seven years, he had already switched employers four times, due to either a “situation” or a “problem”. Job-hopping like this is rare among foreign workers.

Every time he was let go and went back to Bangladesh, his parents would borrow more money to send him back to Singapore - racking up more debt paying agents who charge anywhere from S$2,000 to S$5,000.

“There was a time when my father told me not to go back to Singapore anymore. He even told our relatives not to give me money,” Mukul recalled. “But my mother loves me too much. So she sold her jewellery for me. And my friends in Singapore helped, too.”

Meeting Lai Yong gave Mukul a place to escape to, at least on the weekends. He volunteered as a translator at HealthServe where he easily made friends with both Singaporeans and other foreign workers.

During the week, however, writing verses about loneliness, missing his family, and the hardships of a migrant worker was still his main outlet for venting his internal turmoil.

Over the years, he’d written a large number of poems, some of which he managed to publish in a book in Bangladesh. But he told Lai Yong that his wish was to have them translated into English and published in Singapore, reaching a wider audience.

“Since childhood, I’ve wanted to be different and prove myself to the world,” Mukul said.

In fact, he had been earnestly attending literary events around Singapore, immersing himself in the scene.

TRANSLATING MUKUL

In 2014, Mukul participated in the inaugural migrant worker poetry competition organised in conjunction with the Singapore Writers Festival. He did not win, but it was at that event that he approached Cyril Wong, an award-winning poet and writer from Singapore.

“He was talking a lot in his poetry about how much he was struggling with prejudice in Singapore, and I thought these topics were so powerful,” Cyril said of his first impressions of Mukul.

Sensing Cyril’s interest in his work, Mukul asked for help to recreate his poems in English. It didn’t take much to convince Cyril.

“These things had to be talked about in order to start some kind of literary, political or cultural conversation about what it means to be a migrant worker in Singapore,” said the 42-year-old known for his poems on love and sexuality.

And the poetry was very raw and honest; very tender and painful, but also optimistic. And I found that to be a worthwhile project to do.

The two got to work right away. But Cyril soon realised the amount of work it would take to get Mukul’s poems transcreated and made book-worthy.

“Mukul would send me the poems on WhatsApp and it was really exhausting to read like 60 poems on WhatsApp, just scrolling and scrolling,” Cyril said of their collaborative process.

“A lot of it was Google-translated, so it didn’t make any sense, it was basically gibberish. I would retranslate the English translations into poems that were more literary, more dramatic and more sensible; and then I would talk to him to see whether he was okay with them,” Cyril said.

For months, the two met every few weeks to talk through poems and about life in general.

“I was getting a lot of context from him and that was how I knew how to translate the poems,” said Cyril, who occasionally expressed reservations about recreating Mukul’s poems this way.

“The English poems, they are basically poems in my own voice,” he said. “There’s a certain ethical consideration here.”

Cyril said he would ask Mukul, “Are you sure that you want to do this, because the end product will just be mostly in my voice, trying to imitate what I think is you. Are you okay with that kind of distance?”

Mukul was not at all concerned. “I think he was just happy to see his name in print,” said Cyril.

In 2016, the book Me Migrant was published, and its first print run sold out very quickly.

What no one expected was how Mukul became a media sensation overnight.

LIVING TWO LIVES

Within weeks of the release of Me Migrant, Mukul was on television shows such as CNA’s Singapore Tonight. Even international publications like Bloomberg, Newsweek and The Economist wanted to feature him in their stories.

“I don’t think I could have done something like this in my life if I had just lived in Bangladesh,” said Mukul, reflecting on how that book changed his life. “I presented my lifestyle and honesty to (people) and they appreciated my work.”

He was also invited to give talks at schools, one of which was the National University of Singapore. “I cannot make you understand how I felt, as a construction worker getting to speak in front of such brilliant students,” he said.

While Mukul basked in the whirlwind of attention, his collaborator Cyril felt uneasy with the hype.

“A lot of international media were trying to contact me to talk about the experience of working with Mukul, about Mukul himself,” Cyril recalled. “I was thinking to myself, ‘Why is everyone suddenly so hung up about migrant workers?’

It wasn’t about the poetry anymore, it was about the personality.

"Everyone wanted to talk about the suffering, the suffering, the suffering."

Cyril did not think that this kind of media attention would result in real changes that would elevate migrant workers from their plight.

“I think we are in a phase of culture, regionally and internationally, in which people are very obsessed with poverty porn in order to feel good about themselves,” he said.

But Mukul did not mind. His weekends were packed with invitations to speak at events where he signed books for fans and got to rub shoulders and take pictures with dignitaries.

When Monday arrived, and he had to return to slogging on the construction site, his mood would crash.

“I had two lives in Singapore. One is bright, the other is dull. As a construction worker, there was a pain in me that became worse over time,” Mukul said.

He only wanted to live his “second life” in which “ministers, ambassadors and the high commissioners would come”. “They appreciated me."

Cyril saw Mukul’s transformation thus: “The moment the fame got to him, he became very much imprisoned in this bubble of delusion about what it meant to be an author or a poet.

“He had this innocence, but also a kind of childish delusion that as long as he was famous, somehow everything else – economically and practically speaking – would fall into place for him: He would be rich; he would be able to take care of his parents; he would be able to build a bigger home in Bangladesh.”

Cyril’s concerns were not unfounded. Mukul’s fame was about to cost him his fifth job in Singapore.

WATCH: Mukul pays a price (13:24)

‘THEY’RE JEALOUS’

One man who wasn't surprised at how easily Mukul became a media darling was Cai Yinzhou. When he first met Mukul at HealthServe in 2015, he noticed him right off because the Bangladeshi was “super-friendly”.

The 28-year-old who founded Geylang Adventures, a community group that reaches out to migrant workers, didn’t even know that Mukul was one - because he carried himself so differently. “He was wearing these bright-coloured shirt and pants. And he was always in the centre of a few people, talking.”

“He loves to perform, he loves to hold the microphone. That is him in his natural element... It was a matter of time, you know, when he’s so ‘diva’ as I call it,” Yinzhou added, jokingly.

However, as one of Mukul’s confidantes in Singapore, Yinzhou also quickly realised that while Mukul enjoyed all the attention he was getting, he was also deeply troubled.

Mukul told CNA Insider he felt misunderstood at work, and was particularly hurt by his co-workers’ reactions. “When I did my first live interview, they saw me on TV and they were so jealous,” he said.

They would ask why a poor person like me was busy with writing and stuff? I felt pained.

Mukul also believed that his supervisors made things difficult for him on purpose.

“They would find fault all the time,” said Mukul, who thought that he was an above-average worker and deserved to be promoted. “They would tell me I did not have enough experience, that I needed to go in the field to learn my job before becoming a supervisor.”

However, as a Singaporean, Yinzhou could see why an employer would take issue with Mukul, especially with all his extracurricular activities. “He was always busy on weekends when typically workers would be trying to work overtime, or sometimes being exploited to work overtime.

“But he’d be like, ‘I can’t because I’m the guest-of-honour.’ So it was this power imbalance that would cause tension.”

He also noticed that Mukul would sometimes stretch himself too thin with his social activities, and sacrificed proper rest.

“I don’t know about the rate of sick leave for other workers but for Mukul, he was letting the burden of the lack of rest catch up with him,” Yinzhou said.

“If your heart's not in your work, I think it shows.”

THE OTHER SIDE OF FAME

As Mukul got into more trouble at work, his Singaporean friends tried to talk sense into him. They could all see that if nothing was done, things would not end well for Mukul.

“I was very aware of the realities of his family back home – how they were depending on his income, and what his parents had to sacrifice for him to be here,” said Yinzhou.

“Being conscious of that, I spoke to him about what he could do to upskill himself, how he could be more serious at work.”

Cyril offered Mukul similar advice. “I tried my best to tell him that being a poet will not pay the bills. It will not necessarily make you a better human being.

You have to learn how to take care of others. Stop thinking about yourself as the famous artist poet.

But their words went unheeded by Mukul. And at the end of 2017, he was once again sent packing from his job, and returned home to Bangladesh.

When CNA Insider caught up with Mukul in Patgram in April this year, he’d been jobless for more than a year, waiting for the “right” job in Singapore to come along.

He’d been keeping himself busy, though: His frequently-updated Facebook page had photos of him performing at or attending events, rubbing elbows with local politicians.

He also took up a small bank loan to rebuild his home that was destroyed by monsoon floods. The new place with four bedrooms looked fancier than the houses on the same street, with colourful murals and a front garden with exotic flowers.

Mukul said that while his family was broke, he felt the need to maintain a certain image in a town where everyone knew him as a “famous poet”. He did not even go grocery-shopping – because he has no money.

“I have completely hidden my pain from others,” he said. “In order to deal with the pain, I distract myself by singing and writing.”

He also gave motivational talks at schools and, while CNA Insider was there, held an exhibition of his paintings which he said he financed by selling off a gold figurine.

DOING THE SAME THING, OVER AND OVER

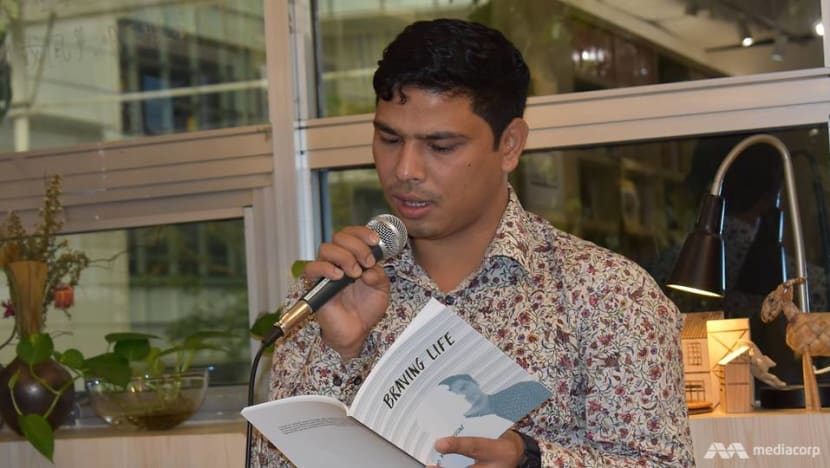

While waiting for a new (and to him suitable) job to materialise, Mukul managed to get HealthServe to help fund the printing of Braving Life, his second book of poems, in Singapore.

This time, however, Mukul had to plead with Cyril to transcreate the poems for him. The latter eventually agreed – which he came to regret.

“I felt like (the book) wasn’t really going anywhere because I kept telling him, as a poet, you need to grow. That is the most repeated advice I gave him that he never heeded,” said the Singaporean writer.

“Mukul just wanted to talk about the same things again and again. He wanted to talk about them in the same way, which is the worst.

"If every poem starts to look like each other, and you don’t care about the artistic process, but more about the fame that accompanies the artistic process, then we have a problem.”

That experience soured their friendship.

"I feel like I’m enabling his delusion about what he can achieve, and should achieve in life. I don’t want to be the person responsible for that," said Cyril.

Indeed there was a sense of déjà vu about events – right after the Braving Life was published in 2018, when Mukul travelled back to Singapore to do publicity for the book, he actually lost yet another opportunity to work there.

His 56-year-old father, who borrowed S$4,000 for Mukul to make this job happen through an agent, does not know what happened.

“I just know that there were problems,” Kapil said. “He came back after just 24 days. It definitely felt bad. If he had stayed I could have asked money from him. Now I cannot do that anymore.”

Reflecting on Mukul’s repeated attempts – and failure – to lead a double life as a migrant worker and poet in Singapore, Lai Yong wonders if Mukul should keep trying.

“Is Singapore the right fit for him as a construction worker, I really don’t know,” he mused.

“It’s 33 degrees out there. A cement bag is 30kg. You can write poetry on it, but it doesn’t lighten it. So, can he get a supervisor role? But he doesn’t have the years of construction foreman experience. So it’s tough.”

ONE LAST CHANCE?

But reality sometimes forces hard choices to be made. With Kapil falling chronically ill, Mukul was finally feeling the pressure of being the family’s breadwinner.

“I really never thought about my family before. Now I have to think about it,” he confessed to CNA Insider.

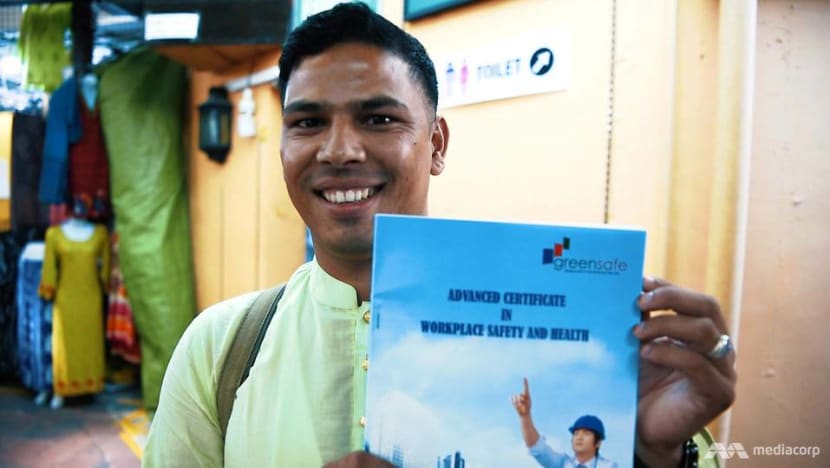

In July, three months after CNA Insider first met him in a state of limbo, Mukul finally got his wish of returning to Singapore.

He’d snared the post of safety coordinator with a construction firm. This would be his seventh job in eleven years.

“They promised to give me an opportunity to study, that's why I came,” said Mukul, who is now attending weekend classes on workplace safety and health.

With his hair cropped short, he now looks younger, but he speaks with noticeably less self-assurance. And there is an air of seriousness that was not here before.

He said that all those months of idling at home waiting for a job had finally made him realise how important qualifications are. As much as his Singaporean friends tried to help him find a job, every time they asked for a CV, he felt ashamed that he had nothing to put on it.

When told he was back in Singapore, Lai Yong had this advice for Mukul: “Just do one thing, and do it well. The bells, the hoops, the whistles can come later, because if you don’t do it well, you’ll be sent back.”

For now, Mukul says he will use his spare time only for studies. He is going to try to get a part-time diploma in civil engineering so that he can progress further in the construction industry.

As for the social events he used to attend and the volunteer work he used to do, they took up too much time and did not really add up to anything that would improve his life, he told CNA Insider – so he is going to give them a miss for now.

But that doesn’t mean he’ll give up writing.

He’s planning to get a book of short stories published in Singapore, he says. “I have 13 short stories so far. When I have around 15, I will publish.”

More on CNA Insider’s Life After Singapore series:

The migrant worker who founded a polytechnic

How Singapore left its mark on a backwater village in Bangladesh