Navigating taboos, parents grapple with sexual stirrings of children with special needs

When puberty struck, one conservative mother had to learn to support her girls' sexual development while coming up against the taboo around the topic. It took her years to find the kind of advice she was seeking.

For the longest time, the best Jacqueline Ang could do to help her twins was to give them space and soft toys to hug for comfort.

SINGAPORE: Jacqueline Ang’s eldest daughter was 10 years old when it happened for the first time.

The girl was at home lying on the floor, her body trembling. After a while, she got frustrated and cried.

“What was she doing?” wondered Ang, who could not imagine at first that her daughter was trying to masturbate. It was also not something she could ask her daughter, whose severe form of autism meant she was non-verbal.

After observing the girl for a period of time, however, her actions became apparent.

“She’d put her hands at her private parts, and then she’d even try to put things at her private parts,” recounts Ang, 44. “Eventually, she also did it at school. So the teacher also saw it.”

The girl’s younger twin sister followed suit a year later.

Both of them were diagnosed with a similar form of autism when they were two and a half years old. Now at the age of 18, they have the intellectual development of two-year-olds.

In taking care of their special needs growing up, it had not crossed Ang’s mind that she would have to confront the issue of sexuality in a special way too.

“I thought it would just come naturally and they’d adapt to it naturally, and that was it,” she says. “As parents, we always focused on ... whether they could go to school (or) take care of their own daily living.”

But when puberty struck, this conservative mother had to find ways to support their sexual development while coming up against the taboo around the topic.

It was only last year when the Disabled People’s Association (DPA) organised its first sexuality workshop for people with mental and physical disabilities, and their carers.

The event was a small one and not publicly promoted. But that was when Ang saw that she was not alone in trying to get a handle on sexuality in youngsters with autism.

She also found practical advice to put into action — all part of a journey she has learnt to embrace.

THREATS DIDN’T WORK

When her eldest daughter started masturbating at school, Ang’s first reaction was to threaten her if she did not stop, for example by taking out the cane to scare her.

“That’s how we were brought up,” says the mother of three. “When we didn’t behave, our parents punished us, and then we’d fear the punishment (and) not do the behaviour.”

That approach, however, quickly got her nowhere.

“I realised that it wasn’t effective ... The more we scolded her, in fact, (the more) her emotions just broke. The meltdowns were very frequent. Then we also got frustrated,” she recounts.

She decided to bring the subject up during a yearly assessment with the paediatrician. The advice she got was to guide her daughter to a private setting and “give her space because she needs to have that space”.

Ang hoped that the issue would go away, but it got to a point where, with both twins trying to masturbate, she had to deal with it daily.

WATCH: Sexuality and my teenage children with autism (7:25)

“I think the more we tried to stop (it), the more they’d come back (to it),” she says. “When they ... didn't get to do what they'd wanted to do, they'd scream, cry, and we could see that they were frustrated.

“Even if you gave them toys, food, things that we could give usually, they wouldn’t calm down.”

They also tried to masturbate in public, the effect of which went beyond their parents having to face “embarrassing moments”.

“We wouldn’t feel like wanting to go out, until maybe months later that we manage to pick up the courage,” says Ang, who works at the Singapore University of Social Sciences.

“Because every single time we go out, it requires a lot of planning, especially if we're going to new places and we know that they’re going to have new experiences. And we don’t know how they’d react.”

She went online to look for more information, but what she found was “very general and (scratching the) surface”. The only solution, it seemed to her, was to give her twins space.

It was hard for her to speak to other parents — who seemed to share their experiences only if they had boys, and not girls, with special needs — or even to her husband and other family members.

“I also had a mental block. As Asians, we’re very shy of talking about such things,” she says.

“But over the years ... I realised that I shouldn’t stop them but see what ways I can help them to cope with it. But honestly speaking, I just thought, ‘But I don’t know how.’”

The best she could do, besides giving them space, was to buy bolsters and big soft toys for them to hug for comfort.

PRONE TO MISCONCEPTION

Relationship counsellor and clinical sexologist Martha Tara Lee acknowledges that it is only human for parents of youngsters with special needs to react in the way Ang first did when her twins tried to express their sexuality.

“Parents are just trying to do what they can, based on what they know,” says Lee, referring to the tendency to punish.

“Besides deterrence, I think it’s also avoidance, like ‘I don’t want to deal with this — maybe this is just a one-time thing’. But if it goes on for a long period of time, then it can become a habit.”

Hence it is important that youngsters with special needs “learn the difference between public and personal space”. For carers to teach these things, however, it would help to change their misconceptions first.

“We just assume people with disability don’t think about sex (or) have sexual needs,” cites Lee, who attributes this to a lack of representation of people with disabilities in popular media.

“With people with mental disability, they may not understand what’s going on, but ... as they come into puberty, they find themselves getting horny. They may find themselves getting erections (or) having wet dreams.

If nobody explains all these to them, then they may feel confused (or) scared.

DPA advocacy lead Sumita Kunashakaran agrees that carers are often taken aback because these sexual awakenings “seem to come out of nowhere”.

She also thinks these are hard conversations for parents to have because of “the environment that we’re in”, where the topic of sex and “what healthy sexual relationships look like” is “culturally sensitive”.

For this story, CNA Insider had reached out to other parents too, and all declined to talk.

Discussing sex is not something that is often done for people with mental disabilities even in clinical settings, acknowledges psychiatrist Chong Siow Ann, the Institute of Mental Health’s vice chairman of its Medical Board (Research).

“To be honest, sexuality is rarely discussed during clinical consultations with mental health patients, unless it’s in the context of some specific sexual disorder or as a possible side effect of some of the medications we prescribe,” he says.

“The normal and natural sexual interests and desires of people with serious mental illness don't often seem as important or even relevant, and are usually submerged by other clinical priorities.”

SEX ED FOR SPECIAL NEEDS STUDENTS

In schools, mainstream sex education for students with special needs focuses a lot on personal hygiene and care rather than emotions and relationships, says Kunashakaran.

“For example, for females, what do you do when having your period, how do you put on a pad, how you use a pad, when you should change it, how often you should wash your private areas,” cites the 32-year-old.

It’s helpful, but I don’t think that’s the be-all and end-all of the conversation.

The Ministry of Education started a pilot in sexuality education in six special education (Sped) schools in 2013.

In 2015, the ministry also awarded a S$24,000 tender to a company to develop a guide to help Sped schools design programmes in personal safety and relationships — amid growing concern over youngsters becoming sexually active and lacking a good understanding of consent.

Research overseas has shown that without proper guidance, people with developmental disabilities are more likely to be sexually exploited than others.

This is one of the reasons disability organisations in Singapore also run sexual education programmes.

“Most of them tend to focus on what’s appropriate behaviour in public, what’s safe (and) what are unsafe touches,” says Kunashakaran. She sees a need, however, for “a lot more of an in-depth conversation” on relationships.

“(Sex education) is very much about how you can address (your feeling or urges) in a safe manner, whether for yourself or the other person that you’re with.”

READ: Court dismisses appeal for intellectually disabled teen who raped schoolmate to be jailed, caned

At the MIJ Special Education Hub, where there are youths in their 20s, the topic of boy-girl relationships is covered under the school’s sex education.

In co-founder and director Faraliza Zainal’s experience with her students, however, behavioural issues tend to be the kind of thing the school mostly works on with parents.

For example, one 15-year-old boy with moderate to high autism used to masturbate up to five times a day in the toilet.

So the teachers gradually increased the interval between his toilet breaks while educating him on masturbation according to Islamic teachings, until the point where they were confident that he had stopped.

Faraliza has been open about discussing masturbation with her son Ashraf, who has autism too and is now 20 years old. But it has not become an issue for her.

READ: Son needed a special school, so they set up one for youths like him

“As he grew older (and) went into puberty, there were a lot of mood swings ... I had to handle. Sometimes he could be happy, then in a split second, he could be very upset about something,” the 49-year-old recalls.

“But nothing about masturbation ... I think because we never allowed him to be on his own, doing nothing. Because the moment he’s doing nothing and he’s exploring ... touching his private parts, that’s when it would lead to something else.”

LET’S TALK ABOUT SEX

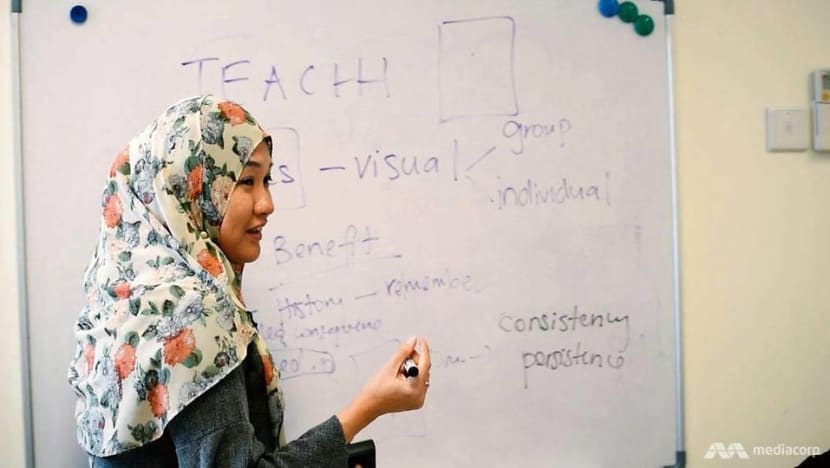

For parents with a lot of questions about their children’s sexuality, the DPA held its first such workshop last year, run by Lee.

It was open to association members, whose children have a range of disabilities: Physical, sensory, learning, intellectual and psychosocial. And the response was “overwhelming”.

“We opened it up to about 20 slots, but I think we had about 50 parents,” says Kunashakaran. “We had to close the registration.”

The workshop topics included personal boundaries, bodily changes, sexual reproduction, emotional and physical sexuality, sexual diversity and societal expectations.

The parents were shy at first, recalls Ang, who attended with her husband. But when she saw Lee “speaking so openly” as a Singaporean woman about the same age as herself, she determined to “take it as a normal (discussion)".

“When I started to share, I realised that the other parents were like, ‘wah, this mother is sharing’. So they also shared. In that way, we started to understand ... this wasn’t an isolated problem,” Ang recounts.

Until that point, even the DPA had reservations about the workshop content because it was “so far out” compared with the association’s usual policy-related work, says Kunashakaran.

We were concerned that ... (it) would be a little bit out there for the parents whom we work with, but they’ve embraced it, and a lot of them were a lot more excited than we expected.

Lee and the DPA are now planning an expanded programme called Di-Sex, including one-on-one consultations as requested by some parents — so people with disabilities or their parents can get “customised information about how they can go through their sexual relationships or the journey through puberty in a healthy way”.

COVID-19 has derailed plans for classes this year, but the DPA hopes to resume the programme in March.

Ang is keen to learn more. She has already been advised to show her twins more physical affection, which she “didn’t do that much” in the past.

“Now, I’m more relaxed. So every day I’d tell my elder one, ‘come let’s have a hug’, or things like that. I just want to give this kind of emotional assurance,” she says.

The girls, who go to Rainbow Centre — where they pick up daily living skills like getting dressed — are now masturbating “much less”, she adds.

She even bought a sex toy online, after hearing from Lee that it could be a useful outlet for their needs. But now she “can’t imagine” them using it, or bringing herself to test its safety and guide them.

Having to grapple with their sexuality, however, meant she was able to overcome her inhibitions to talk through the birds and bees to her youngest daughter, who is neurotypical, studying in a mainstream school and seven years the twins’ junior.

“I practically showed her everything — what a male and female part is ... the science part and the emotional aspect,” recounts Ang. “She seemed to understand when she was eight. Now she’s 11, she knows.

“She did tell me, ‘Huh? I don’t want to have puberty, can or not? It’s a lot of trouble.'”