‘We live in a different age now’: Why Indonesia’s military is unlikely to return to politics

February’s coup in Myanmar has turned the spotlight on other Southeast Asian countries whose militaries have played a significant political role. The programme Insight examines the situation in Indonesia and the prospects for its democracy.

Experts do not believe that Indonesia's military will make a political comeback.

JAKARTA: He was tortured, underwent forced labour and had to eat mice, snakes, lizards and snails to survive.

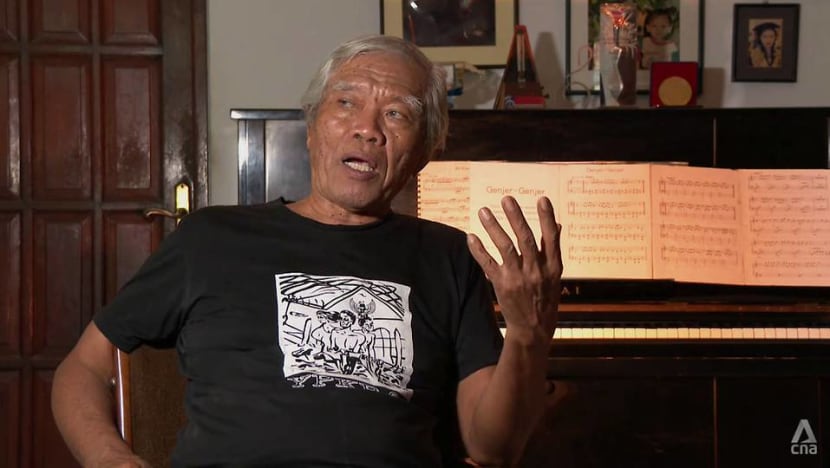

Arrested for being a suspected communist sympathiser, Bedjo Untung was never charged despite being detained from 1970 to 1979, under the authoritarian regime headed by Suharto, the former general.

It has been 23 years since Suharto’s fall, but Bedjo, now 73 and a human rights activist, worries that Indonesia’s military “will always try to play a role” in government.

That has been the case in Thailand, for example, and February’s military coup in Myanmar has cast the spotlight on other Southeast Asian countries whose militaries have played a significant political role over decades.

But is Indonesia’s military capable of making a political comeback following the country’s transition to the multi-party democracy it is today? The programme Insight examines the balance of probabilities.

READ: Myanmar learnt the wrong lessons from Indonesia’s political transition — a commentary

UNLIKE MYANMAR AND THAILAND

Indonesia’s democratic reforms were built on the foundations laid by former president B J Habibie, who took over from Suharto in 1998 and held office for 17 months.

Before that, the Indonesian military played the dual role of security institution and sociopolitical force — and then the latter role was “excised”, noted Leonard Sebastian, co-ordinator of the Indonesia programme at the S Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS) in Singapore.

This is unlike Myanmar and Thailand, “where there hasn’t been that break”.

In Myanmar, prior to the coup, 25 per cent of parliamentary seats were reserved for the military, which also had the power of veto over any constitutional amendment.

In Thailand, the military plays a dominant role in politics. General Prayut Chan-o-cha became prime minister in 2014 after leading a coup. In 2019, he was elected to the role by parliament, whose Senate is hand-picked by the military regime.

READ: Myanmar military never had any intention of giving up power — a commentary

READ: Thailand as a model? Why Myanmar military may follow Prayut's example — a commentary

By comparison, analysts like Sebastian believe democracy is set to stay in Indonesia. For one thing, its military, the Tentara Nasional Indonesia (TNI), has fashioned a new role for itself.

“I can’t see the TNI attempting to engage in the same sort of activities as we’ve seen in Myanmar or Thailand, principally because I think the mindset of the TNI officer is changing,” said the associate professor.

“There’s a desire to be more professional.”

The more important reason why he believes a coup in Indonesia is unlikely is that “we live in a different age now”.

WATCH: Indonesia military (TNI) — Why it’s not getting involved in politics again (3:10)

“Social media is so prevalent in Indonesia with the use of Facebook and Twitter. A TNI soldier can’t engage in any human rights violation without it being captured on YouTube or any of these media,” he said.

And of course, Indonesia’s civil society and media have a tremendous role to play.

HIJACKED FOR POLITICAL INTERESTS

Suharto’s 32-year reign was a period of stability and economic growth for Indonesia. But scholars note that he first hijacked the military for his political interests and embarked on a nationwide purge of suspected communists and their sympathisers.

The death toll of the anti-communist campaign is disputed even today. Human Rights Watch’s Indonesia researcher Andreas Harsono said the numbers range between 500,000 and three million.

Bedjo is still seeking justice for victims of the purge as one of the founders of the 1965 Murder Victims Research Foundation.

“Apparently, I was arrested for being a member of the Indonesian Students’ Youth Association, which was deemed pro-PKI (Indonesian Communist Party). We became scapegoats. What happened to us didn’t make any sense,” he said.

“We became the victims of a power struggle, and we paid the price for it. We were innocent.”

RSIS visiting fellow Noor Huda Ismail said Suharto used the military’s might “for his own purposes”, for instance to annex East Timor. “No doubt he also asked the military to do things that might harm its own people,” he said.

“We (saw) a number of human rights abuses, either in Aceh, Papua, East Timor, also against the so-called ‘kelompok kanan’, the (threat from right-wing) Islamist groups.”

Suharto stepped down amid major riots in the wake of the Asian financial crisis, during which the rupiah lost much of its value against the United States dollar, unemployment rose and prices of basic goods and inflation soared.

And the public does not wish for a return to the old regime or to see the military “involved in politics again”, said Made Supriatma, a visiting fellow at Singapore’s ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute.

“What people want to see is a professional military … capable of handling the security threat, especially the threat that’s coming from outside the country.”

‘RESPECT DEMOCRACY’

Although the military can no longer be involved in Indonesian politics by law and is subservient to the civilian leadership, retired generals do hold political appointments.

Former leader Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, who was president from 2004 to 2014, was a general. In the current Cabinet, there is Defence Minister Prabowo Subianto and Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs and Investment Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan.

Many political parties in Indonesia look to the military as a “source of leadership”, noted Dewi Fortuna Anwar, a research professor at the Indonesian Institute of Sciences’ Centre for Political Studies.

Former officers and generals have been tapped for their experience in management, leadership qualities and the fact that many of them “were already well known”.

“A lot of these Islamic political parties, secular political parties … courted different senior officers,” she said.

“So it’s not surprising if you look at the Cabinet of (President) Joko Widodo — maybe because he’s a civilian and feels the need to have some strong guys.”

WATCH: The full episode — Military in politics: Indonesia (48:07)

Indonesia’s military has regained its credibility, with public surveys showing it to be one of the country’s most trusted institutions, ahead of even the president.

It is one reason that retired generals can become ministers if appointed by the president, or can become the next president if elected by the people, said Coordinating Minister Luhut, 73.

He thinks Indonesia is “more mature” than it was before 1998. “The TNI understand that we should respect democracy … and protect our own democracy,” he added. “That’s the democracy that we love today.”

Watch this episode of Insight here. The programme airs on Thursdays at 9pm.