commentary Commentary

Commentary: Privacy in a pandemic — can I ask my GP if they’ve been vaccinated for COVID-19?

In addressing the ethical and legal questions surrounding vaccinations, we cannot neglect the importance of respecting medical privacy and personal choice, says Michael Wee.

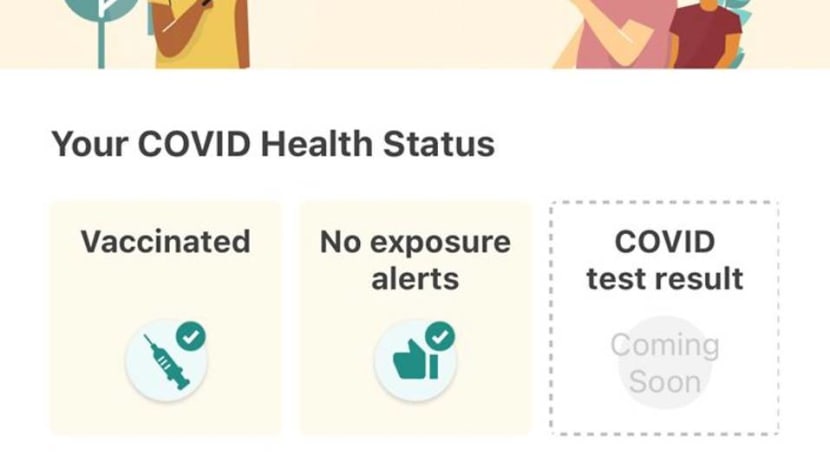

File photo of Trace Together App Vaccination Status

OXFORD: Is privacy dead in a pandemic?

A recurring feature of pandemic life around the world has been anecdotes of strangers “enforcing” COVID-19 rules on others – admonishing fellow commuters on public transport over mask-wearing and social distancing, or even counting guests entering a neighbour’s home.

Whether you think such unofficial acts of enforcement are a form of civic-mindedness or pure nosiness, these at least make reference to rules spelt out in law or official government guidance.

But what about areas of life not currently covered by COVID-19 regulations? Some of the thorniest questions about privacy may well be found there.

READ: Commentary: Flaring tempers and public incidents – are we losing it because of COVID-19?

READ: Commentary: Wear your mask properly! Uncovering the reasons behind public mask shaming

VACCINATION AND PRIVACY

Vaccination, in particular, has raised a host of ethical and legal questions.

For most people around the world, COVID-19 vaccination programmes have thus far been voluntary, and they have been crucial in allowing some form of normality to resume.

At the same time, there are some difficult dilemmas to settle regarding those in our communities who have not yet been, cannot be, or even choose not to be vaccinated.

Take, for example, the subject of so-called “vaccine passports” – for foreign travel, or even to enter pubs and sporting events – which has cropped up every now and then, albeit with little actual roll-out internationally.

READ: Teachers contacting parents and students who have not responded to COVID-19 vaccination invite: MOE

Some worry that vaccine passports would open a can of worms by setting a precedent for using what is essentially someone’s private medical record to regulate access to public or social goods. In the long term, this may have an adverse effect on the equality of opportunities in society.

Another question raised is whether employers should change the work duties of unvaccinated employees to minimise exposure to the virus. In a statement to Parliament in January this year, Singapore’s then-Health Minister Gan Kim Yong answered that this was “unlikely to be necessary, unless there is a resurgence of local cases”.

In a similar vein, the president of the Singapore Human Resources Institute recently told the media that employers should not compel staff to disclose their vaccination status, unless “there is a strong business need”, such as because the role in question is a high-risk one.

Safety may be our paramount instinct in times like these, but such questions also turn on the issue of who, if anyone, should have access to someone else’s vaccination status, and how high the bar is set for a “strong business need” that warrants disclosure.

While employers have to observe legal safeguards on data protection, it may not be difficult for colleagues to indirectly find out each other’s vaccination status if workplace arrangements change. This might lead to some unintended effects – would some people start to “unfriend the unvaccinated” – to quote a recent debate on the UK television programme Good Morning Britain?

READ: SIA to test IATA travel pass for COVID-19 result, vaccination status of passengers

Given that vaccines may – like masks – help people feel more comfortable with resuming normal social interactions, it may not be long before, say, patients request to only see vaccinated doctors, or employees ask not to share an office with the unvaccinated or even students to be seated apart based on their vaccination status. Would such requests be justified?

WHY VACCINES ARE NOT SIMPLY LIKE MASK-WEARING

Perhaps it helps to take a step back and consider whether vaccines are a special case compared with other public health measures seen in this pandemic. Then we can better understand what kind of “rules of engagement” would be appropriate for accessing or requesting for someone else’s vaccination status.

First, to state the obvious, vaccines are a medicine, and hence the usual principle of informed consent applies. Consent, however, is not a simple matter of giving someone the option to tick a box or not. It is also about giving them room to properly consider their own concerns, priorities and limits.

If it became routine and acceptable for individuals to question their GPs over their vaccination status, for instance, there is a real risk that private medical information might end up being circulated on social media in a bid to publicise “safe” or “unsafe” doctors.

Hence, while public information campaigns and encouragement from public figures to take up a vaccine can be valuable in overcoming hesitancy, communities should be careful not to tip over into practices of “vaccine shaming” or other forms of social pressure.

READ: Commentary: Here’s why taking the vaccine is necessary even if it’s optional

READ: Commentary: Misinformation threatens Singapore’s COVID-19 vaccination programme

Second, vaccines are an unusual form of medication — they are given to healthy persons, in order to pre-empt and prevent future disease. Since one is not, strictly speaking, curing someone with a vaccine, but altering a well-functioning body, the bar for safety when it comes to licensing tends to be higher than usual.

Furthermore, the primary medical purpose of vaccines is, generally speaking, to provide self-protection, and this is what clinical trials primarily seek to measure.

That is not to say that altruistic vaccination – being vaccinated to protect others – has no place. Indeed, real-world data for the Pfizer vaccine has been very encouraging in showing that it both effectively prevents serious illness and slashes transmission rates.

Nonetheless, the fact remains that vaccination is not simply like putting a mask on to protect others or maintaining social distancing. Such measures are external to the body and easily removable. But to ask someone else to take a medicine – which always comes with risks – for your sake is quite an extraordinary request, and we should not lose sight of that.

All the more after what has been an incredibly difficult year, with many of our usual freedoms and opportunities in life curtailed, some might start to feel like the body is the last refuge of privacy and autonomy.

Others might simply perceive risk differently, and for various personal reasons, might decide otherwise.

To give a hypothetical example: Suppose someone has had several miscarriages and is desperate to conceive. Even if a particular vaccine has been declared safe in relation to fertility, one can imagine that individual being so risk-averse that they decline it for the moment.

Right or wrong, surely that is an understandable human response with which we can empathise.

(Are COVID-19 vaccines still effective against new variants? And could these increase the risk of reinfection? Experts explain why COVID-19 could become a “chronic problem" on CNA's Heart of the Matter podcast.)

UNDERSTANDING VACCINE HESITANCY

While privacy is not an absolute value in daily life, in certain more sensitive matters such as medical decisions – including about vaccination – it can be useful in helping us negotiate differences.

As a strong supporter of vaccination personally, I might disagree with a friend’s refusal of a vaccine, or even think that it is irresponsible for doctors to stay unvaccinated.

But I can at least try to understand why vaccination decisions can be intensely personal or challenging for some, and this should shape how best to engage such a person on the subject.

This pandemic has, in fact, been a timely reminder that vaccine hesitancy is a far broader phenomenon than the more well-known “anti-vax” movement. Historically marginalised groups in societies around the world, for example, may have typically had negative experiences with governments and healthcare institutions, which might indirectly cause vaccine hesitancy.

READ: Commentary: Why are some countries giving people freebies to get vaccinated?

For others, vaccine hesitancy has to be understood as part of a growing mistrust of governments and big corporations around the world, and not just in the West.

Such individuals may be put off by what is perceived as constant, heavy-handed hammering of the official line – to society’s detriment when vaccinations might be required annually and long-term public buy-in becomes critical to success. Instead, concerns about safety need to be addressed transparently, and respect for privacy should be emphasised to avoid any impression of coercion.

COVID-19 AND LIVING WITH RISK

In the long run, however, how responsible someone’s private choice about vaccination must also be assessed in light of how much risk we are willing to live with – individually and collectively.

None of us can live with zero-risk to ourselves or others. Otherwise, we would never get into cars or play sports. Even disease transmission is not necessarily a special case.

READ: Commentary: Inaccurate public understanding of COVID-19 vaccine efficacy has implications for vaccination rates

To put things in perspective, even seasonal flu can be asymptomatic. While it is not known exactly how much asymptomatic carriers contribute to flu transmission, it is certainly conceivable that you and I may have been part of a chain of flu transmission without knowing it, which resulted in someone vulnerable catching it.

By and large, we accept carrying pathogens as a normal and reasonable part of day-to-day risk — in part because of how much good we would otherwise miss.

Our lives have always been inter-connected, and it is not possible to live in the perpetual shadow of risk, such as by eliminating possible encounters with potentially ill or unvaccinated persons. Respecting privacy, in this regard, can help us not to fixate excessively on risk.

COVID-19 is certainly a bigger beast than seasonal flu, and governments will continue to take steps to contain risk. Italy, for example, has recently made vaccination compulsory for healthcare workers; there is talk in the UK of a similar move.

Mandatory vaccination in certain high-risk sectors like healthcare or commercial aviation may be a reasonable and proportionate risk-containment strategy.

But if we are to prepare for a future where COVID-19 remains with us indefinitely, then giving people space to work out their hesitation could be a more effective way to maintain social cohesion and vaccine uptake than a top-down compulsory vaccination policy that could be prove highly divisive.

Such a move could fuel greater resentment and mistrust of institutions, and might also make populations so risk-averse that we can only see our fellow human being as a potential threat, and might become more disconnected and closed-in as individuals.

The future of living with endemic COVID-19 cannot simply be a question of constantly turning up the dial on public health measures.

It is also an ethical question of balancing risk with opportunity in life. Privacy may be an underrated tool in a pandemic, but it may be key to helping us regain a sense of acceptable risk and, to some extent, normalcy.

Michael Wee is Education and Research Officer at the Anscombe Bioethics Centre, an Oxford-based research institute. In 2020 he became the first Singaporean appointed to the Holy See’s bioethics advisory body, the Pontifical Academy for Life.