Commentary: Whether you like it or not, AI chatbots are coming for your phone

Tech companies are hoping to monetise their massive investments in artificial intelligence, but consumer demand for generative AI in smartphones remains unclear, say Steve Kerrison and Jasper Roe of James Cook University, Singapore.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Most of us are probably feeling “AI fatigue” these days, as we’re bombarded by news and controversy about the increasing role of artificial intelligence in our lives.

Now AI is coming for our devices. Tech giants like Apple, Google, and Samsung are racing to push generative AI into mobile operating systems. This push is driven by market competition, the promise of improved user experiences and potential new revenue streams.

However, this also raises concerns about user autonomy and data privacy. Apple’s recent announcement that it is partnering with OpenAI to bring ChatGPT to iPhones has intensified questions around this technology: Will users have a say in how AI is used on their devices? And what does this mean for their data and security?

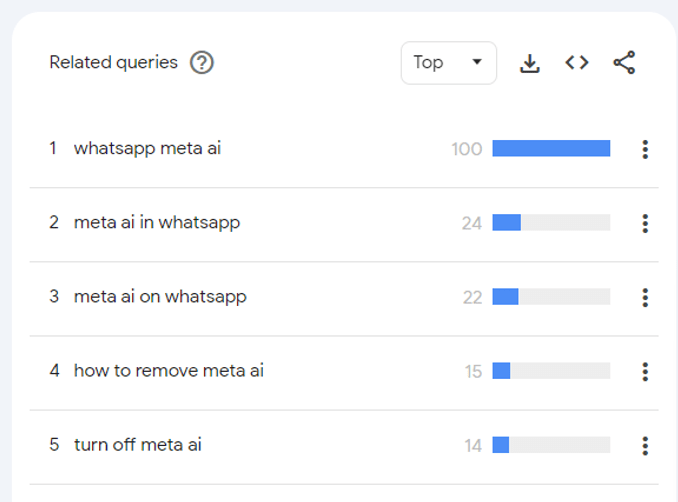

The current public sentiment towards generative AI is shaky, with curiosity being curtailed by the perceived forcefulness of the push to integrate AI chatbots into every piece of tech. At the time of writing, two of the top five Google Singapore searches relating to Meta AI, an AI assistant that was embedded into WhatsApp a few months ago, are about how to disable it.

SOLUTIONS IN SEARCH OF PROBLEMS

The integration of generative AI into smartphones represents a significant opportunity for tech companies to monetise their massive investments in artificial intelligence - but the actual consumer demand for services such as AI-powered search engines and email apps remains unclear.

In fact, we could argue that a lot of new AI features are solutions in search of problems. The real value of having ChatGPT-like capabilities on a smartphone is still up for debate. Are users clamouring for AI assistants, or are tech giants creating a need to justify their investments?

Further to this, should we be concerned about the concentration of power in the tech industry, and the way that we are increasingly exposed to technologies that may have an influence on our digital lives and data?

Before we start reaching for the AI-powered mobile assistant, we need to examine the nature of advanced AI tools. One of the major concerns is that these tools tend to produce confident-sounding, yet inaccurate information.

Having a digital assistant in our pocket that goes beyond Siri’s capabilities is tempting - but what if it tells us something incorrect or dangerous? What if these tools are embedded in children’s phones too? Recent examples include Google’s new search tool, AI Overview, recommending users eat one rock a day and put glue on pizza.

Another issue is cultural sensitivity. We know that generative AI models are trained on internet data which leads them to amplify cultural biases, potentially offending users or providing inappropriate responses.

What does it mean when these Western-centric knowledge bases become available globally? Furthermore, what might the long-term effects of this be as these technologies become more and more ubiquitous?

Regardless of whether AI is good or not, a lot of the pushback seems to be in relation to choice, and there are a few areas where exercising choice is problematic.

Some companies discovered that their staff inadvertently leaked intellectual property to these services, leading to reactionary bans. Samsung, for example, prohibited the use of ChatGPT across its global workforce after an employee was found to have shared sensitive code with the chatbot.

CONCERNS ABOUT DATA SECURITY

For individuals, there are two main areas of concern: Choice over whether to use the technology, and choice over how their own data is used by the technology. While most people likely care more about the former, industry experts and regulators are concerned about protecting the latter, with the European Union (EU) the first to implement rules on how AI can be used.

There is some potential good news, though, in the form of the next generation of devices and their built-in AI capabilities. Apple’s next iPhone will likely be able to run AI models on the device itself, meaning user inputs don’t have to be centrally processed, reducing the risk of data being compromised.

The same can be said of new PCs, with Microsoft leading the pack with its “Copilot+” PC. Microsoft is re-thinking how it delivers some of these capabilities, after controversy surrounding a feature that would maintain a record of everything you did on your device.

But while some companies may err on the way to finding the right balance in how AI is delivered to consumers, one thing that can be said for Apple, is that they are well-regarded for cybersecurity and privacy. Even Microsoft’s China office reportedly mandated that employees use iPhones over Android devices for work.

Despite a trusted track record, Apple is already finding itself at odds with regulators. In the EU, the company was forced to allow third-party app stores - something it doesn’t allow anywhere else.

Conversely, Apple’s new AI technology will not be available in Europe at the same time as the rest of the world because of regulatory concerns, which has ironically led to the EU accusing Apple of anti-competitive behaviour.

Amid all this regulatory wrestling, the consumer’s voice may seem quiet by comparison. But companies will be analysing customer sentiments, search terms and application usage, to see whether the push to adopt AI is working. If it isn’t, they will have to re-think their approach.

So, vote with your wallet and your behaviour, if you want to train these companies to deliver AI to you in the way you like.

Dr Steve Kerrison is Senior Lecturer of Cybersecurity, and Dr Jasper Roe is Head of Department Language School at James Cook University, Singapore.