Commentary: The ripples of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s corruption purge

Two more Chinese military leaders have fallen to President Xi Jinping’s corruption purge. While such dramatic expulsions grab headlines, nabbing individual bad apples does little to address systemic issues that enable corruption in the first place, says Ashton Ng from the University of Cambridge.

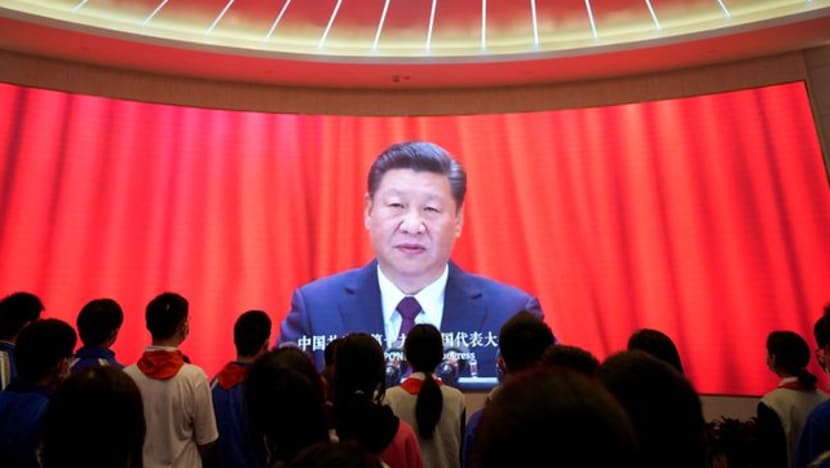

FILE PHOTO: Secondary school students gather in front of a screen displaying an image of Chinese President Xi Jinping, at the Memorial of the First National Congress of the Communist Party of China in Shanghai, China March 10, 2023. REUTERS/Aly Song/File Photo

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Corruption in China continues to make headlines as President Xi Jinping’s crackdown claims its latest victims.

On Thursday (Jun 27), former defence ministers Li Shangfu and Wei Fenghe were expelled from China's Communist Party for accepting large sums in bribes, among other crimes. Mr Li had been abruptly dismissed in October last year.

These announcements come just a week after Mr Xi vowed to crack down on corruption in the military and told top People's Liberation Army (PLA) brass to eradicate conditions that breed corruption.

In a crucial political work conference with military officials at an old revolutionary base on Jun 19, Mr Xi warned of deep-seated problems, stressing the need for political loyalty.

Since last year, 11 PLA generals have been removed from the national legislative body. The PLA's Rocket Force, which controls China's nuclear and conventional missiles, also underwent a surprise reshuffle.

Mr Xi has made fighting corruption a signature priority of his administration since taking power in 2012.

The sheer scale and duration of Mr Xi’s crackdown are unprecedented in the Communist Party’s 100-year history. According to local reports, Chinese authorities investigated a staggering 4.39 million cases and punished some 4.7 million individuals between 2013 and 2022.

The campaign has netted not only low-ranking “flies”, but also high-ranking “tigers” like former Politburo Standing Committee member Zhou Yongkang, now imprisoned for life, and ex-vice minister of public security Sun Lijun, who received a suspended death sentence.

Last year, former foreign minister Qin Gang was fired abruptly under unexplained circumstances.

In May, China sentenced to death a former senior banker at one of the country's largest state-controlled asset management firms for accepting more than 1.1 billion yuan (US$151 million) in bribes. There are also multiple ongoing investigations across the healthcare sector, including several party secretaries.

More recently, on Jun 21, news broke that China’s deputy propaganda chief Zhang Jianchun has been placed under investigation for suspected corruption.

For a public weary of official graft, Mr Xi’s corruption fight is much needed for a cleaner and more accountable government.

Yet, such prominent anti-corruption drives have repeatedly failed to eradicate corruption, despite being vigorously promoted since the 1980s. Each time, corruption resurfaces years later in more sophisticated forms.

FLIES AND TIGERS

In the early years of reform, the most common types of graft were petty bribery and embezzlement by low-level officials. Think of the factory manager stealing inventory, or the local bureaucrat extorting fees from hapless villagers.

As China’s political system evolved, local officials were evaluated on the performance of their economic performance.

The more prosperous the local economy, the more leaders could collect massive benefits. This motivated some officials to strike lucrative deals with entrepreneurs, spurring corruption alongside development.

If left unchecked, corruption corrodes public trust and jeopardises the Communist Party’s legitimacy. Many of the officials now being targeted as “fugitives” were once hailed as competent leaders who delivered impressive economic growth in their jurisdictions.

Earlier this year, China launched a new round of a special operation called Sky Net, aimed at hunting down corrupt officials who have fled overseas. The operation takes its name from a Chinese proverb: Heaven’s net has wide meshes, but nothing escapes from it.

Since its launch in 2015, Sky Net has become a centrepiece of Mr Xi’s anti-corruption crusade. Through collaborating with foreign governments and international law enforcement agencies, China repatriated 140 party members and government officials in 2023 alone, recovering 2.91 billion yuan in stolen assets.

By targeting individuals no longer within China’s jurisdiction, Sky Net avoids prosecuting powerful figures still within the system. This allows the Communist Party to appear tough on corruption without confronting vested interests.

But nabbing individual bad apples does little to address the systemic issues that enable graft in the first place.

China's corruption problem is closely tied to the state's role in the economy, which gives officials substantial influence over key resources such as land, loans and licenses. This can tempt officials to sell favours to businesspeople or collude with state-owned enterprises to stifle private sector competitors.

These problems are compounded by the cultural norm of guanxi (personal connections), which emphasises cultivating relationships with those in power in order to get ahead.

GLOBAL PHENOMENON, CHINESE CHARACTERISTICS

China is not an outlier when it comes to corruption. The United Nations estimates that corruption across the world drains more than 5 per cent of the global gross domestic product. Of the approximately US$13 trillion in global public spending, up to 25 per cent is lost to corruption, it said.

While corruption is a global phenomenon, Mr Xi’s abrupt purges of top-level officials have raised questions about the stability of China’s governance.

As Associate Professor Alfred Wu, an expert on Chinese politics from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, said in a media report: “Xi claimed that China's governance model could become an alternative to the US-dominant world order, but when they keep removing top-level officials abruptly, which country would like to learn this from China?”

Moreover, China has signalled to the world that its anti-corruption campaign has gone truly global.

In 2023, two former executives of state-owned China Railway Tunnel Group were imprisoned and fined in a high-profile Chinese court case for bribing Singaporean official Henry Foo Yung Thye, a former Land Transport Authority deputy group director. It marked the first time China had convicted its citizens for bribing a foreign official.

To succeed in the long run, China’s anti-corruption efforts must upend the incentive structure that makes corruption tempting to local officials.

Economically, this means boosting public sector wages to reduce the need for predatory extraction. In 2015, the government announced a plan to increase the salaries of civil servants by an average of 60 per cent over the next few years.

However, the implementation of this plan has been uneven across different regions and sectors.

The shift towards a more market-driven system must also be accelerated, creating a level playing field for private enterprises. Politically, it requires external audits of deals between businesses and officials, who should be exposed to greater channels of public scrutiny.

As China’s economy matures, the returns on crony capitalism will diminish, while the costs, both economic and social, will mount.

Eventually, the party will have to confront the hard truth: Fighting corruption is not just about catching crooks, but about changing entrenched systems that breed them.

Dr Ashton Ng is Kuok Family-Lee Kuan Yew Scholar in Chinese History at the University of Cambridge and Young NUS Fellow at the National University of Singapore.