commentary Commentary

Commentary: Why Anwar Ibrahim’s longheld dream of becoming Malaysia PM keeps getting thwarted

Anwar Ibrahim has come far from his days as a charismatic firebrand. Now the man who believes in an inclusive Malaysia is seen as a huge political threat, says James Chin.

Malaysian opposition leader Anwar Ibrahim speaks during a press conference after meeting the nation's king in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, Tuesday, Oct. 13, 2020. Anwar met the king Tuesday in a bid to form a new government after claiming he had secured a majority in Parliament. (AP Photo/Vincent Thian)

HOBART: In the past 24 hours, the political climate in Malaysia has changed completely.

Anwar Ibrahim, often dubbed Malaysia’s perennial Prime Minister-in-waiting, met with the Malaysian King on Tuesday (Oct 13) and told him he had the numbers to form a new government.

At a press conference later in the afternoon, he claimed to have more than 120 MPs backing him.

You only need 112 MPs for a simple majority in the country’s 222-seat parliament. If Anwar’s claims are true, his government would be a strong and stable one and the palace should seriously look into the issue. It is widely assumed that Muhyiddin currently has 114 MPs supporting his rule.

Anwar’s meeting with the King was highly anticipated, since the former made these public claims three weeks ago.

The Malaysian police have also said earlier this week they were seeking clarifications from Anwar after undisclosed complaints were made.

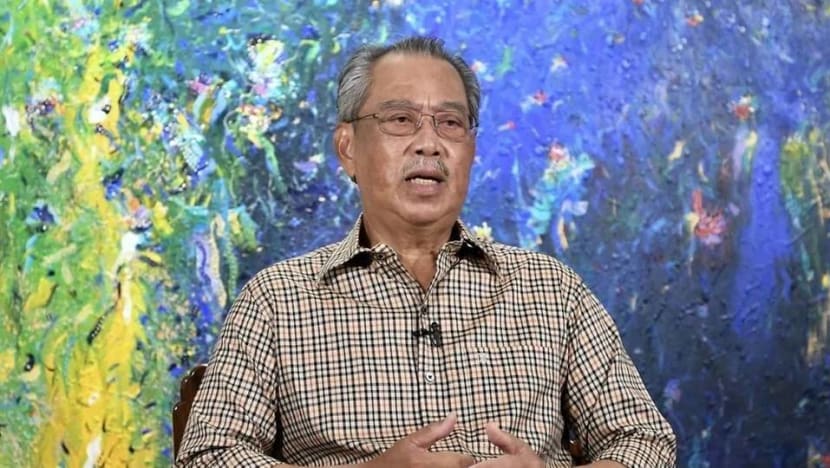

MUHYIDDIN RESPONDS

An hour after Anwar’s press conference, Malaysian Prime Minister Muhyiddin Yassin held a separate press conference. His aides positioned it as a regular media briefing.

But everyone knew it was to demonstrate Muhyiddin was in control. Such press conferences by Muhyiddin since he took over as PM have been very rare.

READ: Commentary: Malaysia goes slow on COVID-19 reopening for good reason

LISTEN: What next for Malaysian workers stuck there and Singapore businesses who hire them here?

Reporters who attended the event were screened, and apart from questions on Malaysia’s reimposed Movement Control Order, there was only one question allowed on what had transpired in the palace.

Muhyiddin brushed the question aside suavely, highlighting he was busy all day looking after state affairs and was not keeping tabs on Anwar’s meeting with the Agong.

In a reply to show he was still in charge, he said he did not know what Anwar was up to but was confident in the King’s judgment and that any eventual decision would take guidance from the Constitution.

In other words, Muhyiddin was calling Anwar’s bluff.

Muhyiddin’s curt attitude towards Anwar’s attempt to depose him is in line with most of what the Malaysian political class is thinking: That Anwar simply does not have the numbers.

Yet why is there so much scepticism towards Anwar? And why is Anwar doing so much to be Prime Minister?

READ: Commentary: Sabah state election ignites fresh Game of Thrones jostling in Malaysian politics

ANWAR’S EARLY DAYS

To answer these questions, you must understand Anwar’s political history. Anwar was a political high flyer who ascended Malaysia’s political ladder rapidly.

During his younger days at Universiti Malaya, as a charismatic firebrand, he energised the student movement. He was so good at it, he was actively courted by many political parties.

In a deft move, he refused to join any, choosing instead to establish his own progressive Malay-Islamic non-government organisation, the Muslim Youth Movement of Malaysia (ABIM) in 1974, so he could lead on his terms. ABIM expanded quickly and became a major political player within the Malay political class.

To the surprise of even his closest friends, Anwar suddenly joined Mahathir Mohamad and UMNO in 1982. After his first election foray, he was immediately catapulted into the role of deputy minister in Mahathir’s government.

From then on, it was clear Anwar was on his way to the top. It was not a matter of if but when.

A SPLIT, A NEW THINKING

All this came crashing down in 1998 when Mahathir sacked Anwar after accusations of sodomy, homosexuality, womanising, corruption and posing a threat to national security.

Anwar was swiftly removed from UMNO. He also lost his deputy prime ministership.

With the hindsight of history, experts have now concluded Mahathir had removed Anwar fearing a threat to his position.

Their public clashes over Malaysia’s response to the Asian financial crisis regarding the imposition of capital controls undermined the government and fuelled suspicions Anwar was taking advantage of the economic turmoil to displace Mahathir and take over the country.

READ: Commentary: Wheels set in motion for another political showdown in Malaysia

READ: Commentary: What’s behind Mahathir’s sacking and Malaysia’s new political drama

Since then Anwar has spent more than 10 years in prison for sodomy and corruption, yet was widely seen as a political prisoner by international human rights groups.

Anwar’s time in prison fundamentally changed him.

Although he still believed in Malaysia being led by a Malay Muslim, he started to embrace the view that non-Malays and non-Muslims must have a place under the Malaysian sun. This was in stark contrast to UMNO and other right-wing Malay groups who consistently upheld the ideology of Ketuanan Melayu, or absolute Malay supremacy in Malaysia.

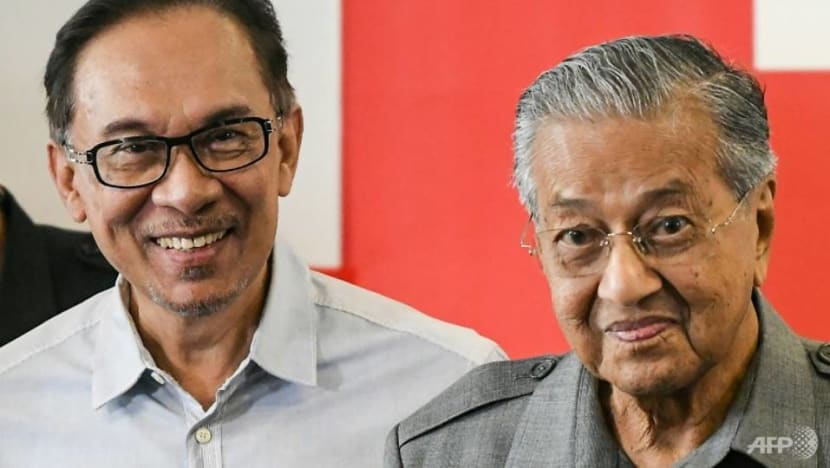

In a remarkable comeback, Anwar and Mahathir reconciled in 2017 to form an alliance to defeat their common political enemy, UMNO and Najib Razak.

READ: Commentary: This is not the end of Najib Razak

Everybody thought Anwar’s moment had finally come when Pakatan Harapan (PH), the new political alliance, won the 2018 general elections. After all, Mahathir publicly promised to step down as PM in 2020 to give way to Anwar.

But the problem was, like all political deals, this two-year transition deal could not be enforced. In retrospect, Mahathir may have had no intention of handing power over to Anwar, preferring to focus on cultivating support for his son Mukhriz.

In late February this year, PH imploded. Muhyiddin Yassin ended up as PM in March with a new coalition government, Perikatan Nasional.

READ: Commentary: Muhyiddin Yassin, the all-seasoned politician, who rose to Malaysia’s pinnacle of power

READ: Commentary: Malaysian politics is going through a midlife crisis

Everybody though Anwar’s political career was over - until he announced he had the numbers to form a new government.

WHAT ARE HIS CHANCES?

But this isn’t Anwar’s first waltz in bidding for the top role. Just think of his many other attempts since 2008.

Anwar’s efforts to assume the prime ministership, even if he does have the numbers in theory, will continue to face huge obstacles from three major political blocks.

First, the Malay establishment and Malay capitalists, who are worried Anwar’s association with the Democratic Action Party and other non-Malay groups mean he will fundamentally change Malaysia’s preferential policies in the long term, which threatens their survival.

Anwar has said publicly just last year that the “obsolete” race-based New Economic Policy (NEP) must be dismantled.

This group has been used to doing business and winning government and other contracts based on affirmative action for Malays and Bumiputera. Many of them genuinely believe they will not survive without the NEP. Billions are at stake if Anwar becomes PM.

Major infrastructure works must allocate a proportion of projects for Malay interests. Similarly, companies must reserve a percentage of shares for Malay interests.

Second, Mahathir and conservative Malay groups. This group thinks Anwar will turn out to be a weak leader who cannot handle non-Malay groups.

They argue Anwar’s record in leading a multi-racial Pakatan Keadilan Rakyat (PKR) will lead him to become overly accommodative towards non-Malay demands, often at the expense of Malay interests.

This group thinks the only way to “control” the non-Malays, especially the Chinese, is to show and exercise strong Malay leadership. Mahathir is the best example of such leadership. When Mahathir says no to Chinese demands, chances are the Chinese groups will not ask again, or try again, the thinking goes.

READ: Commentary: Looks like regime change hasn’t altered the Malaysian psyche

READ: Commentary: Was the Pakatan Harapan coalition doomed to fail from the start?

Third, right-wing Islamic groups. This group has opposed Anwar for years purely on religious terms.

They view Anwar as being too liberal and his appointment as PM as a threat to their goal of establishing a more pious and religious Islamic state.

These ultra conservatives also believe Anwar’s sodomy sentences and various infamous videos, whose authenticity have not been confirmed, showed he has led an abhorrent homosexual lifestyle, a capital sin in Malaysian Muslim society that unequivocally rules him out for any leadership role, much less the top job in the land.

READ: Commentary: Sex videos a weapon of choice in Malaysian politics that distract from other issues

THE COMING WEEKS

Over the next few days, the picture will become clearer as to whether Anwar will indeed get the prize he has been chasing after all his life or if he will have to live to fight another day.

The next steps are out of his hands. The palace will have to verify the intentions of those who say they will defect to Anwar’s coalition.

On top of this, the King may also consult the other eight Sultans under Malaysia’s unique rotation king system, where weighty national matters such as the appointment of the Prime Minister may require the agreement of the Conference of Rulers, the formal body representing the Malay rulers.

You can be sure the three major blocs who have concerns and grievances against Anwar have already started lobbying behind the scenes to shape the outcome.

The unlikely scenario that Anwar does somehow manage to become Malaysia’s ninth PM will be the most remarkable political comeback since Mahathir’s.

But for now, Anwar will remain Malaysia’s Prime Minister-in-waiting.

Professor James Chin is Professor of Asian Studies at the University of Tasmania and Senior Fellow at the Jeffrey Cheah Institute on Southeast Asia.