commentary Commentary

Commentary: US-China ties are set to worsen, before they get better

As proceedings in Alaska showed, both the US and Chinese diplomats were signalling to domestic audiences that they would not back down on issues of interest, says Christian Le Miere.

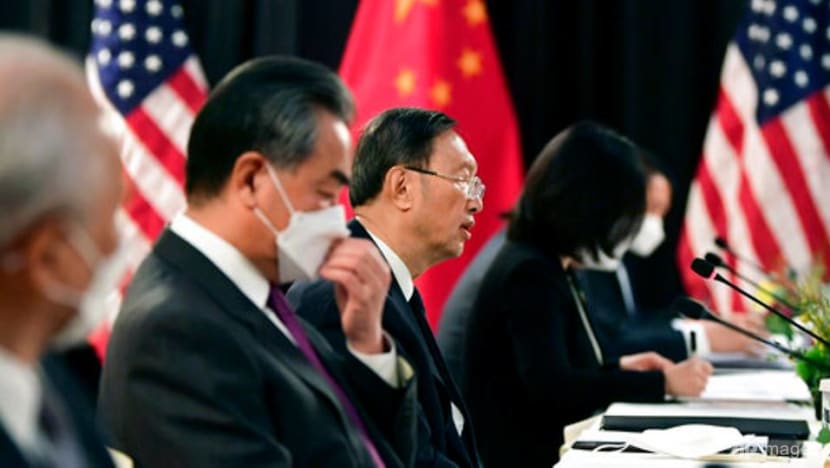

Chinese Communist Party foreign affairs chief Yang Jiechi, center, and China's State Councilor Wang Yi, second from left, speak at the opening session of US-China talks at the Captain Cook Hotel in Anchorage, Alaska on Thursday, Mar 18, 2021. (Photo: AP/Frederic J Brown)

LONDON: The expectations were low, but still they were too high.

The landmark Sino-US meetings held in Alaska opened on Thursday (Mar 18) with a remarkable diplomatic fracas.

Opening comments by US Secretary of State Antony Blinken and National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan noted that the two sought to raise concerns held by the US around issues such as Xinjiang, Taiwan, cyberattacks and economic coercion “frankly, directly and with clarity”.

Politburo member Yang Jiechi responded with a lengthy monologue decrying the US’ intervention in China’s internal affairs, criticising Washington’s foreign policy and urging the US to “change its own image”.

The back-and-forth between the two sides, played out in front of TV cameras, was clearly intended for public consumption. Both the US and Chinese diplomats were signalling to domestic audiences that they would not back down on issues of interest.

And it is this fact that points to the minimal scope both sides have for compromise and collaboration currently.

It underlines a key systemic issue in the Sino-US relationship: Supported by bipartisan political and public opinion, Washington has moved beyond coaxing China’s rise and is now adopting a more adversarial position towards even China’s “core interests” such as Taiwan, Xinjiang and Hong Kong.

READ: Commentary: After Alaska, age of selective engagement in US-China relations begins

READ: Commentary: Expectations for reset in US-China relations must be managed

Beijing, meanwhile, confident in its newfound relative power, is giving any criticism short shrift.

Both sides are avoiding the appearance of weakness and are in no mood to concede.

The initial fireworks of the opening salvo did not last to the end of the get-together, when the read-outs from both sides were far more measured and talked of areas of intersecting interests and the need for continued dialogue.

But the disagreements at the top of the meeting are the clearest sign thus far that the Sino-US relationship has fundamentally altered from the more cautious and measured approach taken by both sides during the Obama era.

The result is a generally more antagonistic relationship, with little space currently for any improvement in bilateral ties. In short, the Sino-US relationship is likely to get worse before it gets any better.

DETERIORATING RHETORIC

The war of words between the two delegations was an unusually bellicose start to proceedings.

Domestic critics of the Biden administration immediately seized upon the fracas as a sign that the administration was weak and not respected by rivals.

“It’s embarrassing but, more importantly, it is also dangerous,” former US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said in a live interview to US media.

“When the Chinese Communist Party perceives weakness (in the US administration) it acts like it did in that room in Anchorage yesterday.”

READ: Commentary: Joe Biden’s quietly revolutionary first 100 days

However, it is certainly not new or unusual for China to push back against US criticism in public, engage in whataboutism or suggest the US is not as strong as perceived.

As far back as 1956, Mao Zedong first referred to US imperialism as a “paper tiger”. Lengthy diatribes against perceived hegemons have been a stock in trade in China’s diplomacy since the People’s Republic was founded.

In December 1950, Time magazine described how a “scar-faced servant” of Mao’s delivered a speech at a United Nations meeting in Lake Success, New York, which comprised “two awful hours of rasping vituperation.”

What has changed is the US’ willingness to publicly criticise China’s activities in uncompromising language.

Since Nixon went to China in 1972, the US has often favoured couching its criticism of China in softer language, with an eye on both opening access to the most populous market in the world and encouraging China to rise within the rules-based system in place since the end of the Second World War.

Even in the wake of the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989, President George H W Bush responded by criticising “elements of the Chinese army,” stating that “this is not the time for an emotional response, but for a reasoned, careful action that takes into account both our long-term interests and recognition of a complex internal situation in China”.

Bush’s diary entry from the day after the massacre said he talked with Nixon, who said “don’t disrupt the relationship…but take a good look at the long haul”.

READ: Commentary: Social media worsens growing anti-China sentiments in Southeast Asia

READ: Commentary: Chinese vaccine diplomacy in Southeast Asia seeds goodwill but has limited strategic gains

Those kid gloves have now come off. With the US now identifying China as its primary threat, and effectively seeing the country’s rise as a negative outcome for its own security, there is now widespread and bipartisan support for a more robust response to China.

Thus, Blinken has already stated that he is in agreement with his predecessor Pompeo in labelling the situation in Xinjiang a genocide.

The US no longer refers to “complex internal situations” in China nor relies on assurances provided by Beijing in private, as the Obama administration did over the militarisation of the South China Sea.

The US’ language toward China now is clear-eyed and direct. China’s response, as should be expected, is firm and at times defensive.

WORSENING TIES

That’s not to say that the two sides are not seeking opportunities for cooperation.

Blinken and Sullivan issued statements after the meetings that highlighted issues such as Iran, Afghanistan and North Korea as areas where the two sides have mutual interests and should collaborate.

The official Xinhua read-out of the meetings also focused heavily on potential collaboration, noting that the two sides should “make the cake of cooperation bigger.”

But the rhetoric in Anchorage, directed as it was to domestic audiences, points to the fact that there is little public appetite for such cooperation.

Senator Chuck Schumer, the Senate majority leader, said in late February that he wants lawmakers to deliver a range of measures to counter China’s rise, reflecting bipartisan hawkishness towards Beijing currently.

Supported by this public and political opinion, the Biden administration is in no hurry to ease tariffs or concede negotiations points to China. And in this more febrile atmosphere, Beijing is in no mood to appear weak or back down first.

READ: Commentary: Is China too big to tame? No easy answers to Quad’s central challenge

Writing in the Atlantic on Sunday, Thomas Wright suggested that the Alaska bust-up was a necessary correction to Sino-US relations to enable frank conversations.

As it failed to upset the rest of the negotiations, he suggested the two sides are therefore communicating effectively.

There is some truth to this, but it does not signal that cooperation is more likely in coming months.

Rather, with more aggressive legislation coming down the track, further decoupling of their intertwined economies and no incentive for either side to compromise first, the post-Alaska Sino-US relationship is set to get worse in the short term, not better.

Christian Le Miere is a foreign policy adviser and the founder and manging director of Arcipel, a strategic advisory firm based in London.