Chinese internet censors ban anti-West firebrand Sima Nan for a year

The ultranationalist blogger has not posted online since Tuesday when he voiced support for Donald Trump in the US election.

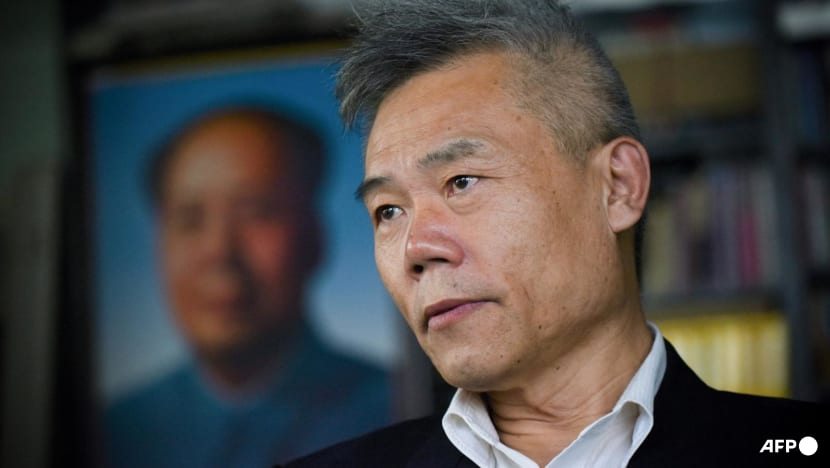

Social commentator Sima Nan looking on during an interview in Beijing. (File photo: AFP/Wang Zhao)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

Chinese internet regulators have banned controversial ultranationalist blogger Sima Nan from posting on his social media accounts, according to sources.

Two sources familiar with the situation told the Post that the ban on the highly controversial Chinese online influencer known for his strong anti-West hot takes was expected to last for a year.

Both sources declined to comment on the reason for the ban.

“He was banned across the platforms for a year. But I can’t talk about what triggered the ban,” said one source with direct knowledge of the matter.

Sima Nan did not respond to the Post’s requests for comment on Friday (Nov 8).

Sima Nan, who first rose to national fame in the 1990s with his criticism of Falun Gong, a spiritual group Beijing later outlawed, has been active and vocal for over two decades.

His real name is Yu Li and he now has more than 44 million followers on Chinese social media.

With no official affiliation, Sima Nan is seen by many as a symbolic voice on the nationalistic left, raging on China’s heavily-censored internet against various targets, from businesspeople to the West and liberal intellectuals.

In those attacks, he often cites Communist Party ideology, including Mao Zedong Thought, leading many in the country to believe that his remarks have some degree of official endorsement.

He frequently accuses groups or individuals of betraying China’s interests and colluding with the United States, an approach that has earned him the nickname “the anti-US fighter”.

In 2021, he became a national talking point after he accused tech company Lenovo of selling state assets for less than they were worth and paying top executives unreasonably high salaries, despite the company’s mediocre performance.

Lenovo’s parent company defended the 2009 sale of an equity stake in the company made by China’s top science academy, saying it was legal and in line with regulations.

But Sima Nan’s comments were widely shared on social media platforms and he went on to post more than 50 videos and articles on the topic, accusing Lenovo of “causing loss to state assets”.

Beijing did not launch any investigations into the matter, despite the widespread debate.

Sima Nan has not posted on Chinese microblogging site Weibo, short-video platform Douyin or mobile social media service WeChat since Tuesday night when just hours before the voting started, he made his last comments on the US presidential election.

In his final post on Douyin, where he has nearly 38 million followers, he jokingly referred to himself as “the deputy head of Trump’s presidential campaign office in Beijing”, expressing support for the Republican candidate.

In his last Weibo post, Sima Nan said he preferred Trump because “Trump’s transactional mentality” might help Beijing to take over Taiwan.

“To put it bluntly, Trump is a trader. He calls himself a great trader. Trump will cut ties with Taipei and trade with Beijing. Everything is for sale for him. The key is the price,” he said on the Weibo post.

There are no indications that the ban on Sima Nan is linked to any other issue.

The blogger has been banned before – for several weeks in August 2022.

This time the ban comes as Beijing struggles – despite repeated official pledges – to convince domestic and international audiences of its commitment to market reforms and support for the private sector.

Beijing’s internet regulators have also in recent months vowed to step up censorship to create a “favourable environment” for private businesses.

As well as censoring comments deemed to be promoting Western ideology, Chinese internet authorities also clamp down on nationalistic voices they see as having gone too far.

In June, multiple Chinese social media platforms said they were clamping down on hate speech related to a knife attack on a Japanese school bus in the eastern Chinese city of Suzhou.

Chinese courts have also jailed radical Maoists seen as challenging Beijing’s fundamental support for post-Mao reform and opening up.

Earlier this year, Hu Xijin, former editor-in-chief of nationalist newspaper Global Times, disappeared from social media for more than three months after his article interpreting a key party economic strategy document was posted – and then deleted.

In the Jul 22 article, Hu wrote that the omission from the document of the phrase “public ownership playing a dominant role” was a “historic change” towards achieving true equality between private and state-owned economies.

However, the “dominant role” of public ownership is enshrined in the party and national constitutions, and Hu’s interpretation drew immediate backlash from conservative bloggers.

Hu reappeared on social media on Oct 31.

In August, prominent Tsinghua University law professor Lao Dongyan was also muted on social media for more than two months, after she complained of being attacked online over her objection to Beijing’s highly unpopular plan to adopt a national cybersecurity ID system.

A media professor in Hong Kong said ultranationalist views spread on social media by influencers like Sima Nan were causing a lot of harm to the confidence of domestic and foreign investors in China.

“If you continue to allow such people to talk nonsense, it will definitely make investors doubt China’s determination to reform and open up,” the professor said, declining to be named.

“So if China is serious about this, the simplest and most practical signalling is to rein in people like Sima Nan.”

This article was first published on SCMP.