analysis East Asia

'The world is crazy': Spate of mass casualty incidents in China reveal pent up grievances and anger

Three public attacks in China's Changde, Zhuhai and Yixing cities that killed dozens, have raised alarm among many, as well as questions about underlying issues facing society.

Three random public attacks were reported in China within nine days, driven by personal grievances and targeting strangers.(Photo: X/@dashengmedia, Kyodo News via AP, Reuters)

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

SINGAPORE: Three mass casualty incidents that played out in just nine days - the recent spate of what seems to be “revenge on society” attacks in China are raising concerns about underlying societal issues and cannot be dismissed as isolated acts of troubled individuals, analysts told CNA.

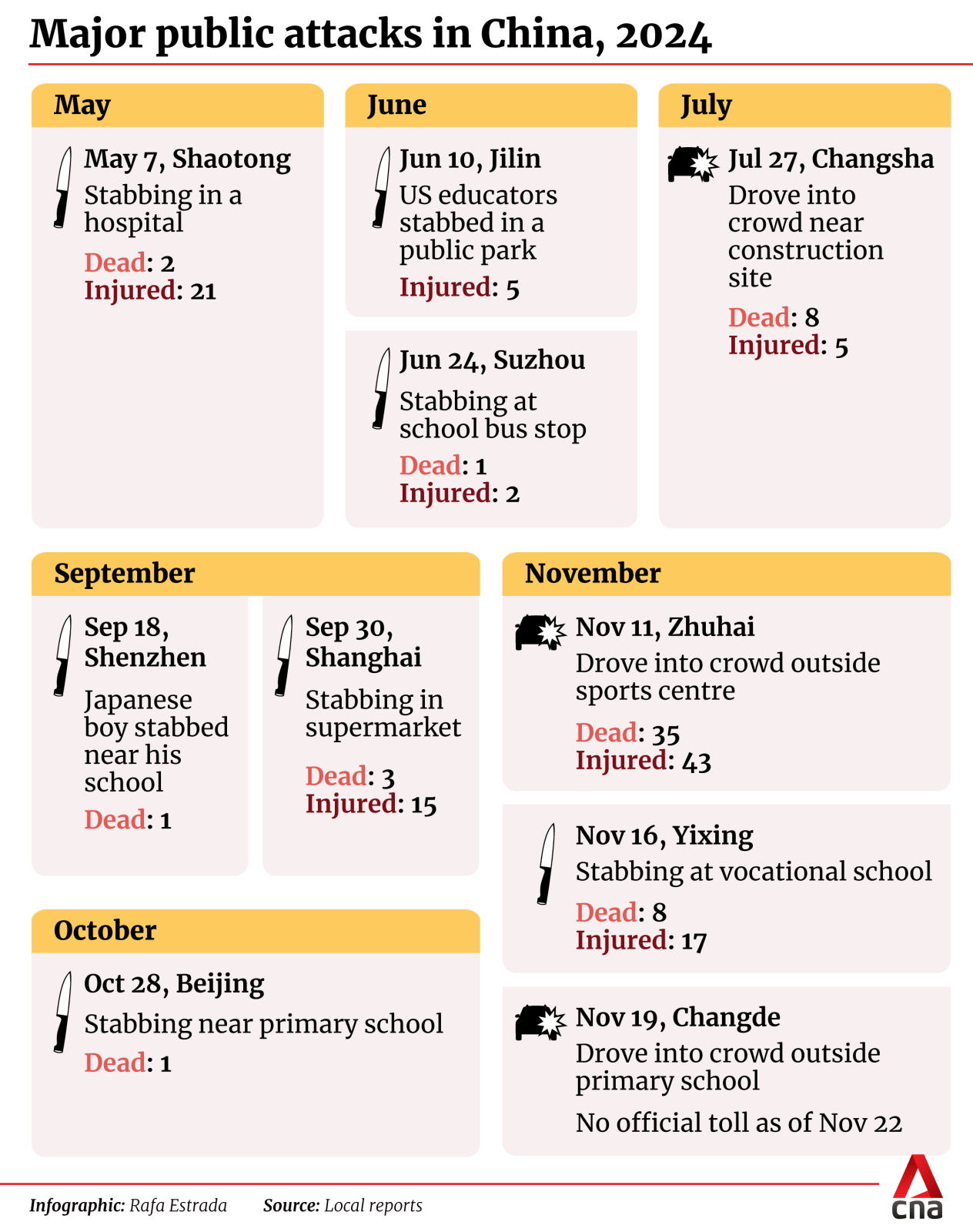

A brutal car attack in the southern city of Zhuhai on Nov 11 killed 35 people exercising at a sports stadium. Days later, a stabbing incident at a vocational college in eastern China’s Yixing city killed eight and badly injured 17 and on Tuesday (Nov 19), an SUV ploughed into students and pedestrians outside a primary school in Hunan’s Changde, where scores of children were seen fleeing in fear.

While the attacker’s motives and the exact injury toll of the latest incident are still unknown, the attacks in Zhuhai and Yixing were “triggered by the dissatisfaction with the division of property following a divorce” and the “failure to obtain a diploma due to poor exam results” respectively, based on police statements.

According to official statistics, violent crime in China is lower than global averages.

The country’s murder rate in 2023 was 0.46 cases per 100,000 people as compared to 5.7 in the US.

But the recent attacks are still raising alarm among many.

In addition to the incidents in November, others have been reported in recent months, including a mass stabbing at a supermarket in Shanghai in September and a stabbing at a top school in Beijing the following month in October.

‘THE WORLD IS CRAZY’

Before posts and comments were swiftly taken down, Chinese social media users expressed anger and shock about the recent killings, asking if it was a sign of underlying issues facing society today.

“They (the perpetrators) are seeking revenge on society,” remarked a user on the Sina Weibo microblogging site in a comment on a state media post about the Zhuhai car attack, which was later removed.

“Why are such incidents happening every day,” asked a user on Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok especially popular among young users.

Another said bluntly: “The world is crazy.”

Dr Zhao Litao, a senior research fellow at the National University of Singapore (NUS), told CNA that while it was challenging to establish a link between the rampage incidents “due to limited publicly available information”, there was a common thread – “their nature of acts as ‘social revenge’ (in which) perpetrators act on personal grievances by attacking strangers”.

“Victims were often random and unrelated to the perpetrators, which highlighted the unpredictability and indiscriminate targeting involved,” he said, adding that the incidents “amplified public concern about whether the pattern reflected deeper underlying issues”.

A police report shows that the 62-year-old perpetrator in Zhuhai took “social revenge” after anger over his divorce settlement. He later attempted suicide and is now in a coma.

The 21-year-old suspect in the Yixing stabbing rampage vented his frustration and “attacked others after failing an exam and not receiving his graduation certificate”, according to a statement issued by the Yixing Public Security Bureau.

He had also been deeply unhappy over his low internship pay, the statement added.

“The complex web of personal traumas and grievances… led them to this fatalistic moment,” said Mr Barclay Bram, a Fellow on Chinese Society at the Asia Society Policy Institute’s Center for China Analysis, who has also researched mental health and psychological counselling in China.

He told CNA that the “inability to find other means of resolving issues, access to weapons, and the social contagion effect of other acts of mass violence” could also be contributing factors.

Dr Zhao said the attacks highlighted structural issues such as socioeconomic disparities, weakened social norms as well as gaps in psychological support.

“Individual mental health challenges are often shaped by broader societal stressors. For instance, work pressures, unemployment, strained relationships, or economic disputes can escalate stress levels,” he added.

“It’s critical to ask how and why individuals transition from normalcy to extremity – and what environmental or systemic conditions might be facilitating this shift.”

A “sustainable approach” would require tackling the root causes of social discontent, Dr Zhao said.

“Policies promoting equitable economic development, robust social safety nets, accessible mental health services and fair dispute resolution mechanisms can reduce the pressures that drive individuals to extreme actions,” he added.

Related:

THE IMPORTANCE OF MENTAL HEALTH AWARENESS

China’s economy is facing a number of challenges – a property crisis, steep public debt as well as rising youth unemployment rates, all of which have taken a toll on both economic and mental health.

Mental health remains a growing issue in the country – with reports of people feeling stressed, burnt out, anxious and depressed. Experts have also cited issues like rising costs of living, high unemployment rates and the lack of state support amid a turbulent economy still in post-pandemic recovery.

“Chinese society is under significant stress due to a slowing economy, uncertain future and an unstable global climate,” said Mr Bram, who also stressed that it was “hard to generalise across a population as large as that of China”.

The long tail of the COVID-19 pandemic and public mistrust caused by the government’s harsh lockdowns “contributed to a sense of hopelessness amongst many in society”, he added.

The Blue Book of National Depression, published by the Chinese Academy of Science in 2022, found that for every one million people in China, only 20 had proper access to mental health services – as compared to 1,000 Americans (per million) who enjoyed those benefits and support in the US.

Experts like Dr Zhao suggested more proactive approaches to promote mental health awareness and encourage empathy. “The role of social support systems is crucial,” he said. “When individuals lack effective avenues to cope with stress or resolve disputes, their frustrations may accumulate to a breaking point.”

But there was also still strong social stigma around treatment and seeking help.

“Stigma often prevents individuals from seeking help, leading many to suffer in silence or keep their struggles within the family,” said Dr Jared Ng, a psychiatrist and also the Medical Director of Connections MindHealth, a clinic in Singapore which provides mental health services to a diverse clientele, including Chinese students studying abroad.

Limited access to care is another challenge, Dr Ng added.

“Psychological support services are concentrated in urban centres like major cities but rural areas have far fewer resources,” he said, adding that early detection and intervention was also crucial in preventing violent episodes.

“Socio-economic stressors can push individuals to their breaking point and when combined with substances like drugs or alcohol, these pressures can escalate into extreme actions including harm to themselves or others.”

Psychological support alone cannot solve the deep rooted issues, other experts said.

“Would increased psychological support be a good thing in this case? Of course,” said Mr Bram. “(But) would it have prevented these instances of social violence altogether? Possibly not, as the dynamics involved are both specific and complex.”

ADDRESSING SOCIAL DISCONTENT

The violent episodes have also raised questions about the ability of the Chinese government to deal with grievances in society.

Following the car attack in Zhuhai, authorities pledged to solve the root of the problem, by better handling issues such as family and property-related disputes.

Though not all are buying it.

“This is what happens when a government prioritises money and economic growth over the welfare of people,” read a highly rated comment on Weibo before it was deleted. “For those in power, achieving wealth and status is more important than people’s lives,” said another user.

Conundrums have existed and persisted over the past decade, said Associate Professor Alfred Wu from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (LKYSPP).

“Beijing has traditionally relied on a top-down approach to governance to manage security,” Assoc Prof Wu said. “But in reality, the central government can’t actually handle so many things.”

“A more effective way would be a rethink on fostering a healthy society and managing that well – including by allowing more grassroots-level initiatives,” he said.

In the aftermath of recent incidents, the more immediate response from authorities was to censor information and discourse on the internet.

Graphic images showing the extent of the crime scene in Zhuhai – blood and bodies lying in the street, were scrubbed off sites like Weibo and comments critical of efforts by the authorities removed.

This level of censorship can be expected, experts previously told CNA, especially in the aftermath of a serious tragedy to “try and control the narrative”.

A post sharing details of the most recent incident in Changde on an official procuratorate’s Douyin channel initially garnered over 4,000 comments. However, the number of comments dropped to less than 80 by the next day.

Checks by CNA also found that comment sections had been disabled on Weibo a day after the incident.

“Such responses (by the Chinese authorities) are largely reactive,” said Dr Zhao, adding that censorship efforts focused more on “containment after incidents occur rather than addressing root causes.”

Assoc Prof Wu said that the Chinese government’s current approach has “not been to solve the problem but rather the people who voice out” – and was aimed more at “blocking” and controlling rather than “easing” the situation at hand.

But some netizens also caution against oversharing and reporting news about violent incidents, out of concern that they might inspire copycat attacks.

“(With a population) of 1.4 billion, there are definitely extremists,” said a user on Xiaohongshu who went by the name Yang Lm, who referenced both car attacks in Changde and Zhuhai. “This is why we shouldn’t report such incidents, there are too many copycat criminals.”

There are some merits to restricting and filtering content on social media, said Dr Ng, who also agreed that it could inadvertently lead to “copycat behaviour”.

“It is crucial that the content being shared does not glorify the incident,” he said.

“Social media platforms have a responsibility to balance raising awareness with protecting the mental well-being of their users,” he added.

While efforts by authorities like “risk mapping and enhanced surveillance” may mitigate immediate threats, they are “far from sufficient” as long-term solutions, said Dr Zhao.

“The unpredictable nature of attacks makes it nearly impossible to identify all potential perpetrators in advance. Moreover, these measures risk alienating communities if perceived as overly intrusive,” he said.

“Policies promoting equitable economic development, robust social safety nets and accessible mental health services can reduce the pressures that drive individuals to extreme actions.”

“Building a society where people feel secure, supported and hopeful is key to preventing such tragedies.”