New Hope for Hard-to-Treat Blood Cancers

CAR T-cell therapy unlocks the potential of the body’s immune system to beat advanced blood cancers.

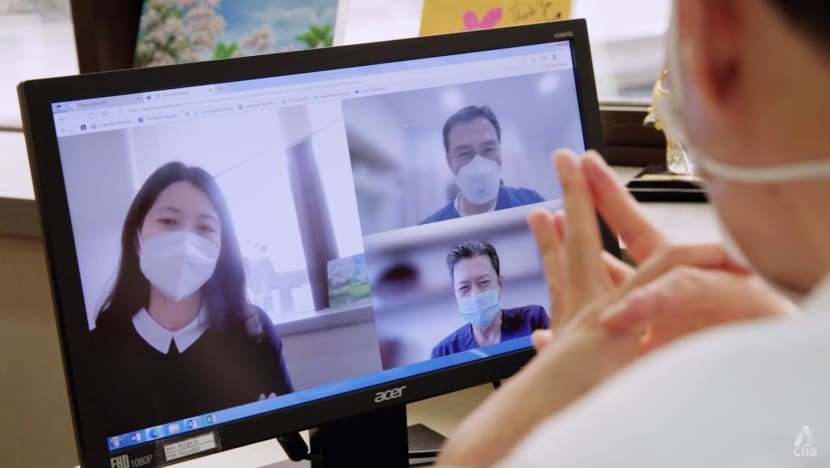

Dr Dawn Mya Hae Tha (right) says CAR T-cell therapy can be used to treat patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and patients up to 25 years of age with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia.

Stimulating the body’s immune system to fight cancer, is increasingly the treatment choice of oncologists in treating patients.

One breakthrough treatment for hard-to-beat blood cancers is CAR T-cell therapy.

This treatment received approval for use in Singapore in 2021 and the country remains the only place in Southeast Asia to have approved CAR T-cell centres.

New Hope for Better Outcomes

CAR T-cell therapy is defined by Dr Dawn Mya Hae Tha as “a form of immunotherapy as well as targeted cell therapy”.

“It is an individualised and personalised treatment for patients with a type of lymphoma called diffuse large B-cell lymphoma” says the Haematologist at Parkway Cancer Centre (PCC).

“Also, children and young adults up to 25 years of age with B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia” she adds, are candidates for the complex course of this new treatment.

Dr Mya explains that the option to use CAR T-cell therapy is considered only when the patient’s cancer is still not in remission following at least two lines of therapy, including stem cell transplantation.

According to Dr Colin Phipps Diong who leads the Haematology team at PCC, before the introduction of CAR T-cell therapy, there was no other viable treatment option, and patients would succumb to their blood cancer.

For eligible patients, says the senior consultant, “CAR T-cell therapy offers hope”.

How CAR T-cell therapy Works

The key to the treatment is the cancer patients’ own T-cells, which is a type of white blood cell that works to kill diseases. However, unlike common infections, cancer cells often behave differently.

“Cancers, including blood cancers are usually able to hide from the immune system … the body's T-cells may have difficulty recognising and attacking blood cancer cells” explains Dr Diong.

The treatment therefore genetically engineers the person’s T-cells to attack cancer cells.

At PCC in Singapore, the treatment is first carried out as an inpatient procedure that lasts for some 3-4 hours, where cancer patients have their T-cells collected through apheresis using a specialised machine.

Saving lives by treating previously incurable blood cancers with CAR T-cell therapy.

The cryopreserved T-cells will be sent to the United States, where a receptor gene known as the Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) is added to the cells. This receptor enables the T-cells to attach to cancer cells with the corresponding antigen, allowing the new CAR T-cells to recognise and destroy cancer cells.

In short, as Dr Diong summarises, “engineering the patient’s own immune cells to kill a specific, intended target”.

After some 3-6 weeks, the modified cells that arrive in Singapore will be ready for the cancer patients who have to first undergo lymphodepleting chemotherapy.

“This is not to kill cancer cells, but immune cells … that might interfere with the functions of CAR T-cells when infused” points out Dr Mya.

Only after that, cancer patients will be able to receive the genetically engineered T-cells through CAR T-cell infusion.

Suitable Cancer Patients for CAR T-Cell Therapy

CAR T-cell therapy is not an option for any cancer patient. Doctors also need to assess the patient to determine if the person is both physically and psychologically prepared to undergo the treatment.

The primary doctor has to present each case in detail to a team of haematologists during regular transplant meetings. This is important, says Dr Diong, as the entire team will “weigh the risks and benefits”.

Apart from the team of haematologists, CAR T-cell therapy treatments will involve a specialised team, from apheresis nurses to transplant coordinators and more. All must work together and even pass audits that a CAR T-cell centre must maintain to remain operational.

Dr Mya recognises the role of the multidisciplinary team in managing potential side effects of CAR T-cell therapy, including cytokine release syndrome (CRS).

The reintroduced CAR T-cells multiplying in the body can release large amounts of chemicals called cytokines into the blood, explains the haematologist. These inflammatory molecules can cause symptoms like fever, aches and pains and in severe cases, lead to low blood pressure and breathing difficulties.

As Dr Diong also points out, “CRS can be a fatal condition”. Therefore, a multidisciplinary team approach that combines expertise, is key in managing patients undergoing treatment.

Patient Outcomes of CAR T-cell Therapy

As the therapy is new, patient follow-ups have not reached the common five years milestone.

However, based on clinical trials, Dr Mya notes that outcomes with CAR T-cell therapy have “tremendously improved”.

“In children with relapsed or refractory B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia… with CAR T-cell therapy, the overall survival is now more than 60 per cent after two years of follow up.

"So, now we can expect a much higher chance of cure for these patients” she says.

Produced in partnership with Parkway Cancer Centre