Gaia Series 105: Can we protect local medical care?

After years of decline and scandal, a Tokyo hospital rebuilds itself through new leadership, returning staff, and reforms that put patient care and community trust at the centre again.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

A Tokyo hospital, once in crisis begins to heal, led by new leadership, young staff and the return of community trust.

In the quiet residential streets of Setagaya, Tokyo, sits a hospital that has served its local community for nearly a century. But behind its neat exterior, Shiseikai Daini Hospital has only recently emerged from a period of deep turmoil. What was once a trusted healthcare institution became a symbol of mismanagement, staff shortages and patient anxiety, before its revival was set in motion by a group of determined individuals, many of them women, committed to rebuilding trust, services and lives.

The crisis began with a scandal that rocked its parent organisation. Kinuko Iwamoto, then chair of the board, was arrested for misappropriating over 100 million yen (S$910,000). Her leadership, marked by years of aggressive cost-cutting, left the hospital severely depleted. Full-time doctors were reduced from 45 to just 27. Entire departments were shuttered. The intensive care unit, once a place where lives were saved, was turned into a storeroom due to staff shortages. Emergency care, once staffed by a team of three doctors, was left to a lone physician, regardless of specialisation. “When a serious case comes in, we’re overwhelmed,” one staff member said. “In such times, inevitably, we’re forced to turn some emergencies away. It’s heartbreaking.”

The public noticed. Bed occupancy fell to just 30 per cent, and the hospital entered a deficit. But the strain on finances wasn’t unique to Shiseikai Daini. A 2024 survey showed that nearly 70 per cent of hospitals across Japan were operating in the red, burdened by rising costs and capped medical fees.

Reiko Saito, who took over as chair following Iwamoto’s arrest, inherited what she called “a negative legacy.” Her first priority, she said, was “to return it to zero. To bring it back to the starting line. From there, we'll move into the positive.” With her came a new era of collective management, replacing unilateral decision-making. The hospital restored regular forums where doctors and nurses could speak openly. “We must work together as one team,” she said.

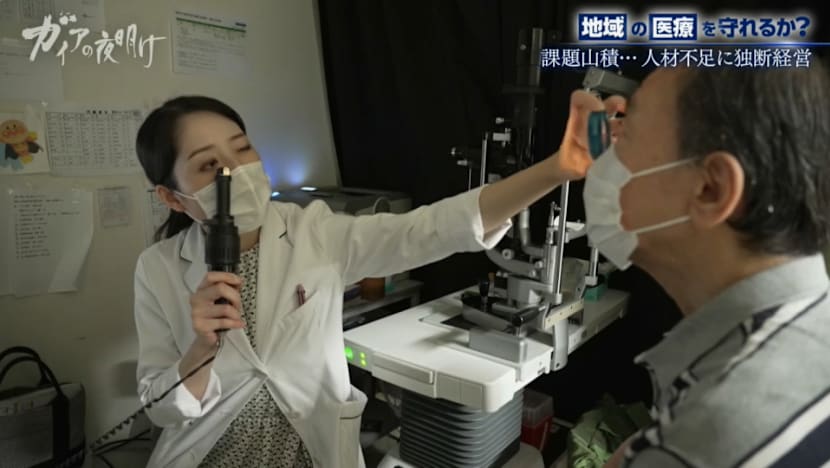

Among the new hires was ophthalmologist Ai Kuranami, 32, a young mother who joined the hospital after its in-house nursery reopened. Previously closed under cost-cutting measures, the nursery was the first facility restored during the reforms. It now operates for two million yen a month, mostly covered through reserves and corporate contributions. For parents like Dr Kuranami, the benefits are immediate. “Since it's in-house, I don't need to drop him off elsewhere. That saves time. It's part of my workplace too. If something happens, I get a call right away,” she said.

Dr Kuranami works with equipment that dates back decades. “This microscope is vital for eye surgery,” she said, handling a piece of equipment more than 30 years old. Still, careful budgeting and new leadership allowed the hospital to purchase a new surgical microscope for over 15 million yen and a modern visual field tester for 7.5 million yen. “It’s a huge relief. It makes surgery easier, and it raises our motivation. It’s the long-awaited microscope, I’d say.”

Despite these improvements, outdated paper charts still line her desk, and investment remains incomplete. But the difference in morale is palpable. “Dr Kuranami’s arrival really helps us all now,” said a colleague. “We’re grateful for that. The most important thing is that she stays.”

Another symbol of the hospital’s turnaround is Dr Norio Yoshimoto, head of the Foot Surgery Centre. A specialist in orthopaedics below the ankle, he is now known as a “super doctor.” But his expertise was once overlooked. “It was about half the amount when I was working at the prefectural or Red Cross hospitals,” he said of his early salary at Shiseikai Daini. “Well, since I came here to learn, I figured that was something I just had to accept.”

Things changed after the scandal. “Now my salary has increased,” he said. “The executives cut their own pay. They raised doctors’ salaries.” Pay is now adjusted according to staff contribution. The number of surgeries he performs annually has surged from 180 to more than 300. His patient list now includes foreign nationals, like Rini from Indonesia, who flew in specifically to be treated for progressive flat foot. “He knows exactly where the pain is and which tendon is broken,” she said. “I’ve been seeing doctors in Singapore, in Japan and even in America. He’s the one who really understood.”

Still, staff shortages remain. While the hospital has gained four new doctors, bringing the total to 31, internal medicine remains a serious concern. “At least three more doctors are urgently needed,” said one administrator. In contrast, nursing is thriving. A full class of new graduates from the adjacent Shiseikai Nursing School joined the hospital, bringing fresh energy. “We all graduated in March,” one nurse said. “We ease patients’ pain. Nurses are the ones closest to their daily lives. We also spend the most time with them. I want to be a source of support.”

Obstetrics also saw dramatic swings. Once renowned, the department was forced to close for a year due to lack of staff. After reopening, births dropped from over 50 a month to just three. The arrival of Dr Naoko Fukuda, 41, helped revive the unit. A specialist in both emergency and intensive care, Dr Fukuda joined the hospital through an open recruitment process that replaced reliance on university-affiliated doctors. Under the previous leadership, nearly half of all doctors came from universities. That figure has since dropped to a quarter.

Dr Fukuda was soon caring for Lulu, a Tanzanian woman expecting her first child. Lulu spoke only Swahili and English, and her husband, Freddy, served as translator. “I love Japan a lot, but being in a foreign country, it’s overwhelming,” Lulu said. The hospital staff had prepared picture cards in multiple languages to aid communication. For Lulu, these efforts meant everything. “Nothing is wrong, and there are no mistakes,” Dr Fukuda told her. “Don’t worry. It’s okay.”

When Lulu’s labour stalled, Dr Fukuda made the decision to perform a Caesarean section herself. Fifteen minutes later, a healthy baby boy weighing 3,768 grams was born. “The doctors and the nurses, even the attendants, all of them are professionals,” said Freddy. “It really makes me trust them. I want to come again if I were to be pregnant again.”

In the path of a hospital's rebirth, a new life was safely delivered. “Medicine exists for people,” said narrator Tetsuji Tanaka, echoing the words of Edo-era pharmacologist Ekiken Kaibara, who once wrote: “Medicine is an act of benevolence, based on a spirit of compassion, with the resolve to save lives.”

Chair Reiko Saito believes the hospital has now reached the starting line. “How do we defend local healthcare?” she asks. “A hospital that's easy for people to come to and also good working conditions for our staff, which will ultimately affect the patients as well. That’s our goal.”