Gaia Series 95: Shortage of nurses in the medical field

Amid widespread strikes and resignations, Japan’s nurses demand better conditions and fight to sustain a strained healthcare system.

This audio is generated by an AI tool.

Japanese hospitals buckle under pressure as chronic understaffing forces nurses to choose between duty and wellbeing.

A national healthcare crisis is unfolding in Japan, as hospitals struggle to retain nursing staff in the face of growing workloads and stagnant wages. In this episode, viewers witness a deeply personal and systemic challenge that has driven nurses to the edge. With over 1,000 hospitals and care facilities joining a nationwide strike, the voices of frontline healthcare workers are no longer silent.

At the National Tokyo Medical Centre, the headquarters of Japan’s largest hospital group, nurses take to the streets alongside their peers in Fukuoka and Sendai. For one hour, they walk out to demand higher wages and better staffing levels. The coordinated strike is unprecedented in scope, involving institutions across the country. “I can't help but feel that our work as medical professionals is being undervalued,” says one nurse. “It's a bit sad. That's honestly how I feel.”

In response, Health Minister Takamaro Fukuoka acknowledges the problem. “We recognise there's a serious staff shortage in medical settings,” he says. “We’ve implemented measures to raise productivity and improve the working environment to support further wage increases.” However, promises of reform may be too little too late.

A 2020 Ministry of Health report estimated Japan had 1.73 million nursing staff. By 2025, a shortfall of up to 270,000 is projected. The episode shows that this future has already arrived. At Nishiyodo Hospital in Osaka, 30 nurses resigned in a single year, pushing remaining staff to their limits. The hospital has 218 beds and about 160 nurses. Night shifts are sometimes covered by just two nurses and one care worker overseeing an entire rehabilitation ward of 60 patients.

Senior nurse Haruka Iyonaga, now in her fifteenth year of service, voices the strain. She also oversees the shift rota, a task that has become increasingly difficult. “Regarding the number of nurses, we really do need more nurses,” she says. “Otherwise, it's just too hard.”

Ms Iyonaga, also a mother, often works late into the evening before rushing to pick up her two-year-old daughter. “I try to leave as early as I can,” she says, “but still some staff remain late on-site. So I try to do what I can before leaving, just to help out.” She often exceeds the standard limit of two night shifts per month for parents, instead taking on about four.

Her junior, Ms Futatsuki, articulates the emotional cost. “We are just chasing tasks, day after day. By the end of the shift, it feels meaningless. All that's left is exhaustion.” These feelings are echoed by others at the hospital, where the inability to hire new staff leaves existing nurses overworked and demoralised.

Hospital management is not blind to the issue. Head of Nursing Yukako Kodama, who has served at Nishiyodo Hospital for 30 years, admits that the current staffing model is unsustainable. “The staffing system has been critically short and chronically lacking,” she says. “As a management team, we feel truly sorry for that.”

Further strain comes from a change in the national medical fee system. Nishiyodo Hospital does not perform surgeries, so revisions that devalued internal medicine fees have led to a projected loss of about 30 million yen (S$264,000) annually. “We can no longer allocate our budget for hiring nurses,” says Ms Kodama, who is visibly emotional when reflecting on the nurses who left. “Even now, I wonder what could I have done differently?”

To stabilise operations, the hospital begins assigning dedicated night-shift nurses. Mr Yusuke Matsuki is the first to take on this role. “It’s only just begun, but I’m not finding it hard,” he says. “I don’t mind night shifts.” With an additional allowance of over 6,000 yen per shift, the new model brings some relief to daytime staff, though it is only a partial fix.

While experienced nurses struggle, new ones are in short supply. Enrolment at Nanao Nursing School has dropped dramatically. “When I entered, it was still competitive,” says Year 3 teacher Sachiko Nakamae. “But now, we're nowhere near full capacity anymore.” The 2023 Noto Peninsula earthquake further reduced applicant numbers. And the nursing school enrolments nationwide prove it: In 2018, at its peak, there were 67,026 students; in 2024, there were only 56,142.

Despite these challenges, students like Kurea Otsumi remain committed. “I had planned to return to Wajima, so I took out a student loan,” says Ms Otsumi, 21. She passes her national exam and begins work at Wajima Hospital. “I want to gain skills and knowledge and become a nurse that people can trust,” she says.

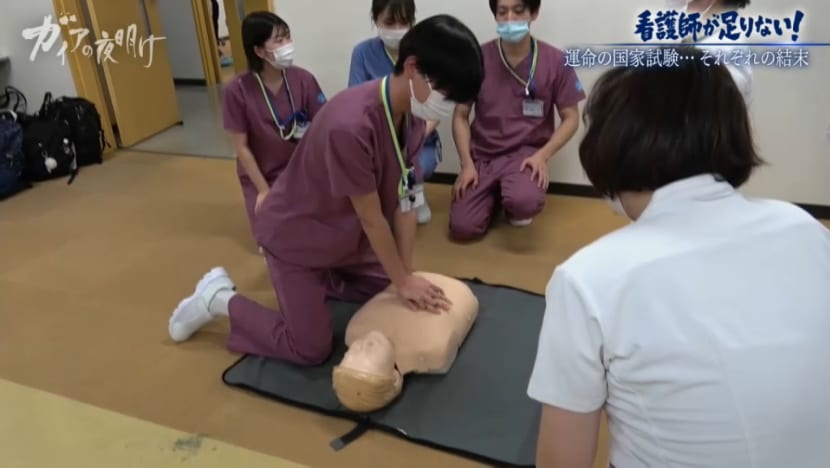

Class representative Ryusei Satake shares a similar motivation. “During the earthquake, I was in an evacuation shelter. I saw disaster nurses up close and thought I wanted to be one too.” After passing his exam, he joins the emergency department at Nippon Medical School Hospital. “I feel like I've taken a small step towards my dream of joining DMAT,” he says, referring to the Disaster Medical Assistance Team.

From resignations and strikes to hope and determination, this episode captures a profession at a crossroads. As one trainee reflects after receiving a thank-you letter from a patient, “It read, ‘You were my angel during my hospital stay.’ It made me so happy. Even though people say it's a tough job, moments like that make me want to become a nurse.”