Civilising China? A contentious social credit system moves boldly forward

A social experiment, in which good behaviour is rewarded and undesirable acts face repercussions, is raising questions about what the future holds for the Chinese. Get Real investigates.

Environmental hygiene is a criterion in some of the social credit systems that have been implemented.

SHANDONG: In his village of about 3,000 people, cleaner Wang Zhaosheng is one of six Five-Star Residents. It is a title he earned after returning a lost wallet and one his wife thinks is a “great honour”.

He also received a trophy from the village leaders. And on a public hoarding outside the village centre, his name is displayed along with the names of the other best-behaved residents.

Good deeds are expected of the residents of Donghuotangzhai in China’s Rongcheng region. And there are several signboards around their village to remind them of values like honesty.

More than reminders, however, there is a system to discourage bad habits: A social credit score assigned to each resident based on his or her behaviour – a rating with consequences, from rewards to sanctions and inconveniences imposed by the authorities.

Rongcheng, in Shandong province, is one of over 40 local governments across China that have piloted versions of this social credit system since the central government laid out a plan in 2014 to implement a national system by next year.

READ: Commentary: Actually, China’s social credit system isn’t the first

READ: Commentary: Rating citizens - can China’s social credit system fix its trust deficit?

Social credits could also apply to citizens' financial standing and the finance market, as the programme Get Real discovers. (Watch the episode here.)

But is this experiment a cure for uncivilised behaviour or a tool to silence dissent? And could it create a new chasm between the haves and have-nots?

Watch: Cleaning up China, with social credit points system (5:34)

FROM MESSY TO SPOTLESS

For the residents of Donghuotangzhai, it all started in 2015. Their village was to be redeveloped, and they were moving into a new government housing complex.

The village committee decided that a system was needed to keep the new premises from degenerating into a slum.

“We used to be messy. We were a village after all. We put our stuff haphazardly,” says social credit system director Wang Fengbo.

“Back then, dunghills would pile up between houses … So our original intention was to raise the residents’ reputation and overall quality.”

It worked. The streets are now spotless, and Donghuotangzhai became a model village in Rongcheng within three years. Residents knew that their every move was being watched and tallied for their social credit score.

Starting with a base of 1,000 points each, they were evaluated. Help those in need who are not their blood relatives for more than six months, and have five points added. Be a public nuisance, and have 20 points deducted.

For every RMB100 (S$20) donated, two points are given. For littering or breaking village rules, points are deducted.

Getting paid to record the deeds, both the good and the bad, of her neighbours is Ms Zhou Aini, one of six information collectors here. Since the system began, she has been keeping tabs on more than 200 households.

To meet a monthly quota of five deeds, she sometimes resorts to recording her own actions. Once, for example, she bumped into a neighbour who was on the way to the supermarket and gave her some vegetables and fish.

“She lives alone. Her husband is deceased, and she has kidney failure,” says Ms Zhou. “I felt as if I was helping her in her time of need.”

Every month, she submits a record of everything she has seen and heard to her supervisor Ms Wang, a party cadre who is on the village committee deciding who gains or loses points.

Why is such a system needed? According to Tsinghua University’s associate professor Qu Wei, an expert on social governance in China, “it’s essentially a method to regulate citizens’ behaviour”.

In the past decade, a string of misdeeds in the country have made world headlines, such as the case of a toddler left for dead in a hit-and-run crash.

These have called into question the state of morality not only among its people but also its companies, like the vaccine maker that sold substandard rabies vaccine, and the lending platform behind one of the biggest Ponzi schemes in China.

READ: China's Changchun mayor resigns after vaccine scandal: Report

READ: Singapore police recover S$27 million linked to China Ponzi scheme

Some incidents had tragic consequences, like the melamine milk powder scandal that killed six babies, and evoked fears about the safety of Chinese-made products.

In a climate of low societal trust, four fifths of 2,200 Chinese netizens surveyed last year by a Berlin university approved of social credit systems as a source of information on the trustworthiness of organisations and citizens, and for promoting honest dealings.

“We know social morality takes a long time to cultivate,” said Assoc Prof Qu.

Traditionally, the law is too powerful. While moral judgement can restrain behaviour, it isn’t powerful enough. This is why we need the social credit system to act as the middle ground.

NIGHTMARE FOR SOME

The central government has outlined the broad strokes of the system, which has a publicly accessible “red list” of model citizens and companies, as well as a blacklist. Local governments have been left to decide how to implement it.

Rongcheng is now lauded by officials as one of the best examples of the system. For some residents, however, it has been a dystopian nightmare.

In the village of Zhaojiashan, 20 minutes away from Donghuotangzhai, the social credit system was rolled out last year, with scores also starting at 1,000 points.

As sanitation in the village was one of the worst in the district, local official Ma Junfeng designed the system to change that through ratings linked to environmental cleanliness.

“You lose five points for every offence … Litter once, that’s five points deducted,” he cites. “We didn’t have to spend a single cent to tidy up (after that). It was all through the efforts of the masses.”

But everyone, young and old, must also earn at least two points every year, or face the consequences.

“If you reach 1,002 points, I’d give you festive benefits and subsidised agricultural services. I give them out according to village regulations. But if you don’t reach the standards, I won’t give you benefits,” he explains.

I must make sure villagers feel the impact of their points, otherwise they wouldn’t listen to me, right?

For village leaders overseeing the system, there are also selfish reasons involved. If points are deducted owing to poor standards of hygiene, that could affect their wages and chances of promotion.

So clean-up brigades are organised, for example to prepare for the district management council’s monthly inspections. That is why Mdm Yu Shu Qing volunteers to clean the streets – to earn two points for eight hours of labour.

“My family is big. Even if I’m tired, I have to do this, otherwise we get nothing,” says the 57-year-old, whose household of five must earn at least 10 points, even though her husband has chronic asthma and stays in bed mostly.

They earn less than RMB400 a month and depend on government handouts to get by – help that could be cut if their score falls too low.

To make matters worse, they lost five points after a neighbour reported them to the village committee recently. The reason? An untidy goat pen.

“For the common folk, earning points and money is really not easy,” laments Mdm Yu, who keeps going out of fear. “We’re all afraid of the punishment. Who isn’t?”

Despite the unhappiness, the system is implemented strictly in Zhaojiashan. Every week, village committee member Xiao Fenglan inspects the households and expects them to keep their yards neat. She makes no exceptions to the rules, even for the elderly.

One of the lucky few, however, is 84-year-old Zou Lizhong, as the cut-off age for the social credit system in his village is 80. He will not lose his welfare benefits, even if he does not volunteer.

But he is concerned about the other residents, most of whom are elderly. “Even before they reach 80 years old, they’d have lost the ability to labour,” he says.

“Especially for peasants, they’ve been toiling since young, so when they reach 80 – 70 even – they can’t do it any more.”

Mr Zou, the village deputy secretary two decades ago, has been a party member for more than half his life. But he opposes the current methods. “You have to labour without getting paid. Isn’t that increasing the burden?” he argues.

“In the party meetings, all the village representatives just raise hands in agreement. You can’t voice your opinions. I don’t think this is good. The people are very frustrated about this matter.”

AN OPEN SESAME

In the villages, the social credit system is still in its infancy. But across China, one company has created a private scoring system with half a billion users, which is over a third of the population.

Ant Financial, which runs Alipay – one of the country’s largest online payment providers, with more than 700 million domestic users – is one of eight companies authorised by the People’s Bank of China to experiment with credit scoring.

And for Alipay user Chloe Lei in Hangzhou, opting into its Sesame grading system – which has a score range of 350 to 950 – has brought conveniences.

After her behavioural preferences, spending, payment habits and even academic qualifications were analysed, her score came up to 805.

Thus considered trustworthy, she gets privileges ranging from deposit-free bicycle rentals to fast-track visa applications, higher loan amounts and even easier access to public services, like quicker payment at the hospital.

“It’s fair that a person with a high score would enjoy conveniences,” says the cosmetics executive.

For others (without privileges), it’s probably because they flout the rules. For example, they don’t repay their loans, or they break the things they borrow. So it's relatively fair. There’s no absolute fairness.

Peking University finance professor Dou Erxiang believes China’s financial market needs such a system. Banks have been reluctant to give loans to individuals and small businesses because there has not been a hub to track credit histories.

“In China, each bank is like an isolated island. Each bank thinks the data it has is too precious to be shared. As a result, loan defaulters can tackle each bank one at a time,” he explains.

“Take advantage of Bank A, then move on to Bank B. If many people are doing this, it creates a systematic risk. The chain of information about a person’s account is fractured.”

Although the Sesame Credit is not part of the state-run social credit project, it has grown into a powerful scoring system in just four years and gives a peek into what the future might hold.

There are forums full of netizens asking how to raise their scores, and people offering to do this for a fee. One man claimed he could raise a Sesame score by up to 30 points, for about RMB270.

But as Get Real found out, it turns out that loan sharks are using the system to find potential victims – people with low scores who would not qualify for bank loans.

Assoc Prof Qu’s biggest worry is that such scoring systems would widen the class divide, as the scores are linked to one’s social and economic status, even one’s address.

“The social credit systems we see are ultimately about distributing society’s resources,” he says.

“Those with good credit scores are likely to come from richer families. Why do we say it’s easier for students from elite schools to get employed? Because apart from knowledge, they have access to a lot of other resources.”

VICTIMS OF BLACKLISTING

China is already seeing the beginnings of one country, two classes. Its red lists of the most trustworthy people and its blacklists are accessible online – one layer of the social credit system that has gone nationwide.

For those blacklisted – over 14 million individuals and businesses – life in China can come to a halt. Take, for example, Mr Tao Mingjian, who ran a company producing construction equipment until he defaulted on more than RMB670,000 in loans.

“I was sued in court. After they enforced the ruling, I wasn’t left with many assets that could be seized. So they could only blacklist me to cause inconvenience in many aspects of my life,” he recounts.

He found out that he was blacklisted, however, only when he was denied a high-speed train ticket. By the end of last year, the system had blocked the purchase of 17.5 million flight tickets and 5.5 million high-speed train tickets.

“Previously, taking the plane or the high-speed rail was so convenient. But now I can only travel by car,” he grouses. “Your spending is limited. They’ll cut off all your cards so you can’t use them.”

His current status makes it hard for him to find employment or restart his business. And as long as he remains blacklisted, his son and daughter would be denied entry to some good schools, the military and the Civil Service.

“Of course I’m worried. I live for my children,” says Mr Tao, who now drives a taxi and sleeps just five hours a day to get by, clear his debts and get off the blacklist.

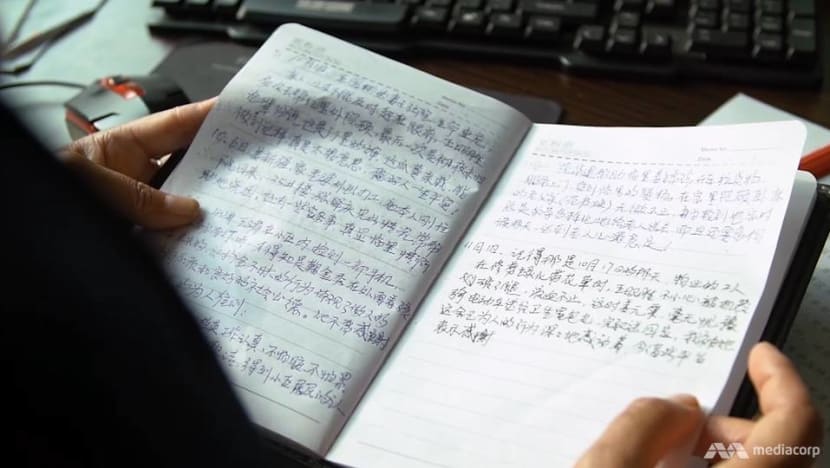

For journalist Liu Hu, who is also on a blacklist, the way out is less clear. In 2015, he shared an article on social media questioning a businessman’s earnings. He was sued for defamation and lost the case.

“After I paid the fine, they said I didn’t apologise. And because of that, I got on the blacklist. Does an apology have anything to do with my financial status? Should I have landed on the blacklist?” he questions.

He eventually published an apology last April, but the court was not satisfied. He has since been seeking redress through the courts and other channels. Nothing has worked, which means he still cannot buy a property or get a loan.

The 44-year-old says this is not the first time he has been wronged. In 2013, he was arrested and accused of “fabricating and spreading rumours” following his reports on misconduct by officials. After two years, the prosecution dropped the charges.

China already has the world’s biggest network of closed-circuit television cameras. “Theoretically”, this gives “what's happening all over the country” visibility, notes Mr Joshua Chin, who has reported extensively on surveillance technologies in the past two years.

READ: From dispensing toilet paper to shaming jaywalkers, China powers up on facial recognition

“The fundamental idea behind the social credit system is to track and shame people into behaving in the correct ways. So surveillance technology will play a pretty important role,” adds the political reporter in The Wall Street Journal’s Beijing bureau.

“It’s reasonable to expect that they’ll be relatively successful in tracking a large number of people, if not everyone.”

Whether or not China can then achieve its goal with the social credit system, one thing is for sure: It will be the largest social engineering experiment the world has ever seen.

Watch this episode of Get Real here. New episodes air every Monday at 9pm.