Intrigue, scandal, heartbreak: The case of South Korea’s missing ‘frog boys’

When five boys did not return to their village one day, their parents had to face their worst nightmare, and it became one of the country’s most notorious missing persons cases. It still is an unsolved mystery.

Five boys aged nine to 13 went on a romp up a mountain. Everything changed for their families after that.

DAEGU, South Korea: The phone call came on the fourth day. “I have the children. They’re all suffering. Two are very ill,” said the voice, who asked for a large sum of money.

Finally, hoped the parents, they could find their children. So they went to the designated place — with the police. But no one came. After waiting for an hour, they returned home, feeling helpless and miserable.

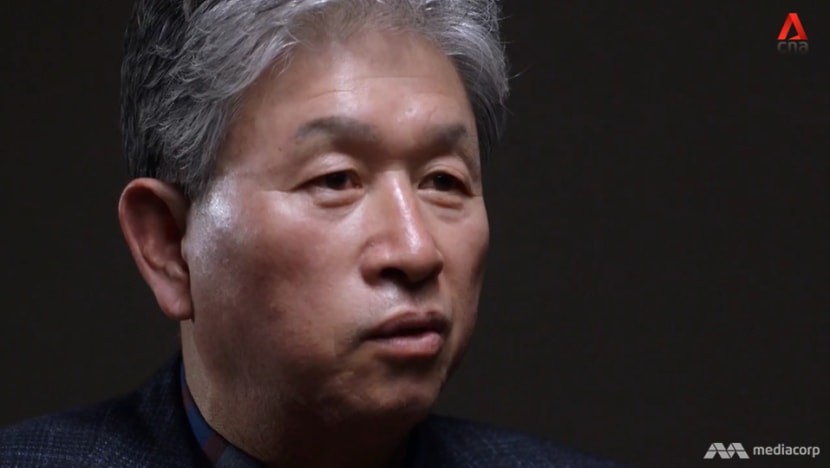

Kim Hyeon-do could talk about the case “forever”, even though it makes him cry.

But words go only so far to plumb the depth of his hurt, and he hopes “no one in this world will ever go through what we went through”.

Nobody else paid much attention, however, the day he and four other sets of parents faced their worst nightmare when their children went missing.

South Korea was preoccupied with its first local elections in 30 years. And the police regarded the boys, aged nine to 13, as runaways. It became one of the country’s most notorious missing persons cases.

“No one was able to solve the case of the five missing children. Isn’t that shameful?” says Woo Jong-u, one of the fathers.

There were reportedly over 500 leads, which all turned out to be false. There were twists and turns, police theories and conspiracy theories. “But there are no answers,” says Park Geon-seo, another of the fathers.

They are still searching, however, for the criminal. They recount the events as if these had happened yesterday, as if the retelling for the CNA special, In Search Of The Frog Boys, might provide clues to solve a 29-year-old mystery. (Watch it here.)

‘CLOSER THAN BROTHERS’

The families were living close together in a village outside Daegu city. Their houses formed a circle, and the children often hung out near the paddy field in front.

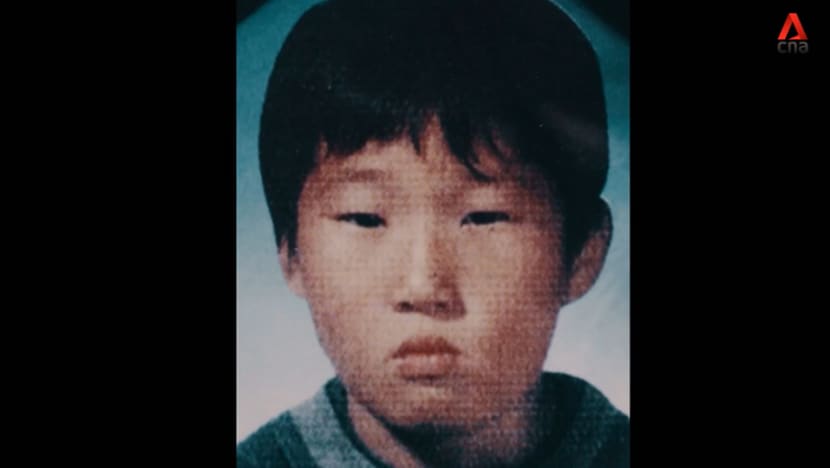

“The boys were closer than brothers. They were like five musketeers,” Woo says of his son Cheol-won and the rest, Chan-in, Ho-yeon, Jong-sik and Yeong-gyu.

Some of them were the only children. Chan-in’s father, Park, said: “In some ways, we were dependent on him. He never gave us any trouble, and he was almost too sincere.”

Kim was also “very close” to his only son, Yeong-gyu. “We tried to give him all the love he deserved, and he loved us back,” said the man. “He was very bright and cheerful. He had a great personality.”

They went missing on March 26, 1991, which was a public holiday because of the elections.

“My son came back to get a thicker jacket,” recalls Woo. “I asked him where he was going, but he never really answered. He just said he was going to play outside.”

It was 9am. At a little past 1pm, he got a call from the taekwondo academy because his boy had not turned up. Soon afterwards, he realised his child was not the only one missing.

“A friend told us he’d seen the five boys. He asked them where they were going. The boys replied that they were going to find lizard (salamander) eggs. That’s why we thought the boys had gone up the mountain,” he relates.

Up on Mount Waryong was an army base on the left, a pond on the right and a shooting range above the pond. The parents started searching the mountain but found no sign of the children.

By late afternoon, reporters heard from the police that five boys had been reported missing.

“At the beginning, it wasn’t very important news. The pro-democracy movement was growing in Korea, and … everybody’s attention was focused on who’d be elected,” recalls Jang Joon-young, who was then a novice journalist.

“The reporters and the police officers thought that the children were just out playing till late.”

After being told to wait for their children to eventually come back, the already panicky parents became frustrated.

They also pointed the finger at each other, remembers Woo. “They shouted, ‘It’s your fault our kids went missing! It’s because you didn’t look after the children!’”

That night, Kim had a dream. “It was pouring. My son was right outside the door. He peeked inside, but without a word, he was gone,” he says.

“I ran after him, calling his name. But he wouldn’t even turn to look back.”

A HUGE NEWS STORY

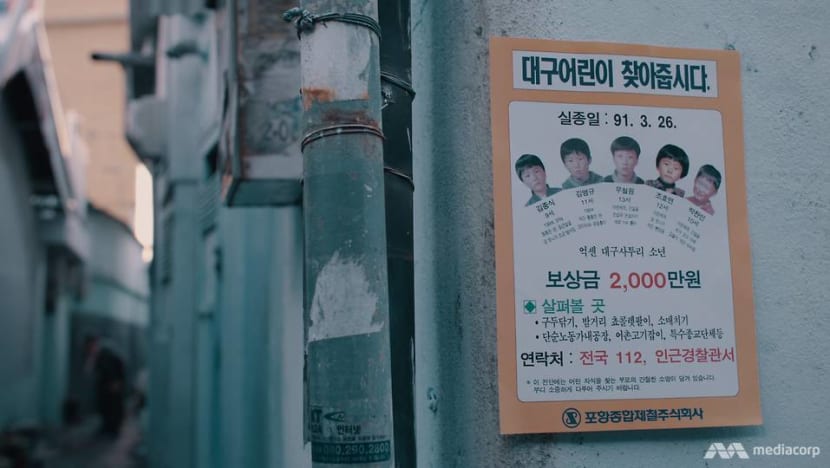

Word eventually spread of the missing children. Five or six days after their disappearance, there was the first news broadcast about five boys “still missing after trying to catch frogs”. Thus they came to be known as the frog boys.

“Within two days, it became city-wide news. After a week, everyone was talking about whether the kids were still alive. Then the story became nationwide news,” recalls Jang.

“Every life is important, but this case was extraordinary because it was about five kids.”

On May 4, the parents participated in a news programme called The Square Of Public Opinions, in which they expressed their dissatisfaction with the investigation. They protested, for example, at police pamphlets that called the children “runaways”.

“This indicates that the police are trying to wrap up the case quickly,” one of the fathers said on the programme. “We want them to change this.”

The live broadcast from the boys’ Seongseo Elementary School was a “very rare” nationwide event and the “biggest opportunity to make this case known”, Jang describes.

It did get a “tremendous amount” of attention — and a sudden phone call, from someone thought to have been one of the boys.

The call was cut off, but the telephone operator said on the programme that it was Jong-sik, sobbing and asking for his mother.

“Everyone applauded and screamed, ‘The kids are alive somewhere!’” Jang recounts. “Everyone was saying, ‘Let’s look for them now. Where are they?’”

But it turned out to be false hopes, just as it was with the first phone call the parents had received. It was a prank.

After the broadcast, however, “more effort was made” to find the children, Woo acknowledges. The then president, Roh Tae-woo, even made a statement about the case and ordered a further investigation. Thousands were mobilised to search for the boys.

For a year, the mountain was searched, with volunteers forming lines to probe the undergrowth as they moved forward.

“The police looked for any evidence they could find. But by then, there was no point in searching because there were no traces left. The police were just following orders … so they just pretended to do something,” says Park.

“We, the parents, meant nothing to them.”

THEIR TORTUROUS TREK

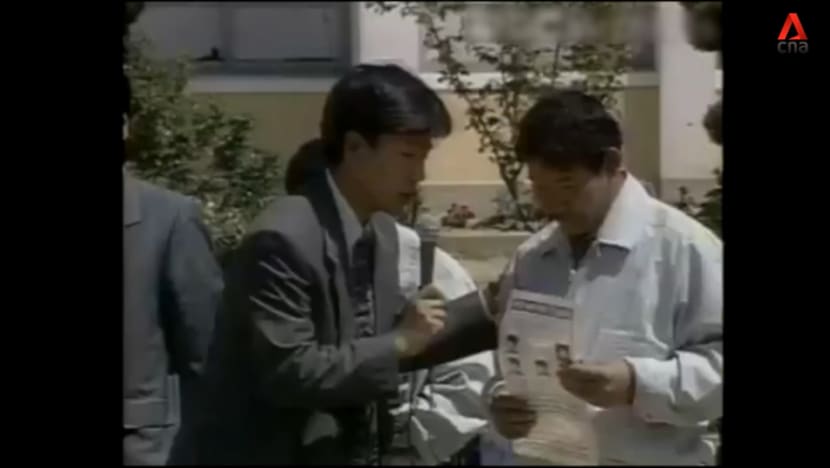

The five fathers were determined, however, to do everything possible for their missing children. They had quit their jobs, rented a small lorry and kept searching across the country, come rain or shine or snow.

The lorry had photos of the children pasted on the sides and coated to withstand rain. Written below were the words “please help find our missing children”.

“We could do nothing more. We couldn’t get any help from experts … so we handed out pamphlets in public places,” recounts Park.

They were joined by Na Ju-bong, who was moved by their appeals. And he saw close up the hardship they went through.

“One day, we noticed that Yeong-gyu’s father looked pale, and his face was turning blue. He was addicted to sleeping pills,” recalls Na, who is chairman of the National Organisation of Finding Missing Children and Family.

“We realised that even a strong man was losing his health after a while. Seeing the fathers become weaker like that, I couldn’t turn my back on them.”

Kim could not sleep because he was thinking of his boy. “I was scared that I may encounter my son in my dreams. I felt helpless as a parent,” he says. “I couldn’t see the point in living any more.”

Woo adds, “Many of us were angry and in pain. Some turned to alcohol to overcome their anger.”

But in public, they had to hide their problems and feelings. And they still had to meet journalists from all over the country.

A year after the boys’ disappearance, however, reporters were not the only ones taking notes during these media events.

“So I asked one of them whom he worked for,” recounts Na. “He gave me his business card … Other than his name and his contact number, there was nothing else.

“I saw the same person again at the next media event. I later found out that he was from an intelligence agency.”

The fathers were being followed by men who were recording their movements and their interviewers.

“They even sent some people to our homes … and reported everything to their bosses. Who on earth treats the parents of missing children like this? Instead of suspecting us, they should’ve been searching for the kids,” Park says indignantly.

“What they did to us was absurd.”

The men said they were protecting the parents, according to Na. But he doubts they were.

At the time, the news reports about the missing boys “kept pointing” to the army base on Mount Waryong. And he kept wondering why the police were “not investigating the military, when everyone was mentioning the military”.

A BOLD ALLEGATION

The parents themselves had wondered if the case was connected to the military because of the shooting range nearby — and because of something else.

“On the day the children went missing, Cheol-won’s friend heard a gunshot and then a scream. Then there was silence,” recounts Woo.

“We went to the boy and asked him if it was true that he’d heard a loud noise. And he said yes.”

But the police did not treat the tale as “serious evidence”, says Park, “so it just stayed a rumour”.

After a few years, people’s interest in the investigation “started to fade”, says Jang. “Only the parents still cared. The public thought the police had done all they could.”

It was “heartbreaking” for the parents, recalls Kim, when the press coverage stopped. “We went to every newspaper in Seoul,” he says. “They kicked us out of their offices because of our demands.”

But the fathers also got into debt after their nationwide search. And they had to take care of other family members. So, three years after the boys’ disappearance, they announced that they would return to their jobs.

Two years later, when they finally had rebuilt their lives, there was an allegation levelled at one of them, which the police did investigate.

Kim Ga-won, a criminal psychologist who had studied in the United States, claimed that the children were buried in Jong-sik’s house because his father “couldn’t account for the first three hours on the day the children went missing”.

At the time, there were hardly any criminal psychologists in South Korea, “which made everyone trust him”, explains Na. This professor also said he had read about the investigation and had “analysed all the evidence and footage”.

The other parents told him that his assumptions were wrong. “Some rumours were believable, but others we couldn’t believe at all,” says Park. “It’s impossible that someone would murder his own child and bury (the child) under his own house.”

Despite the disbelief, the police searched the toilet. They found children’s shoes, “which made them think this might be a possibility”, recounts Na.

“They ended up digging with an excavator,” he adds. “Jong-sik’s father was in agony. People started to think, ‘Could he really have done all of this in three hours?’”

The media were there, filming the event, and many people had gathered to watch. The house was ruined, but nothing was found.

“Kim Ga-won started running away, through the crowds. Some people yelled, ‘Catch him! Catch him!’ He was taken to the police station for his own safety,” Woo narrates.

Archive footage shows that Jong-sik’s father, Kim Cheol-gyu, was livid about the “ridiculous theory”. He died of liver cancer five years later, still in his forties.

“I think he became sick because of the exhaustion of searching for his missing son,” says Woo.

BONES AND BULLETS

A year after his death, and 11 years after the boys’ disappearance, their remains were found on the mountain, on Sept 26, 2002. They were tangled together, in an area a couple of kilometres from their village.

When the parents arrived, there was “already a group of people who’d gathered to see the bodies”, remembers Woo. Only bones, and clothes, were left.

“My vision became blurry, and I started to cry. It was hard to believe that my son was buried here. But I had to,” he says.

“About 30 minutes later, we all became quiet. I realised that my relationship with my son was over.”

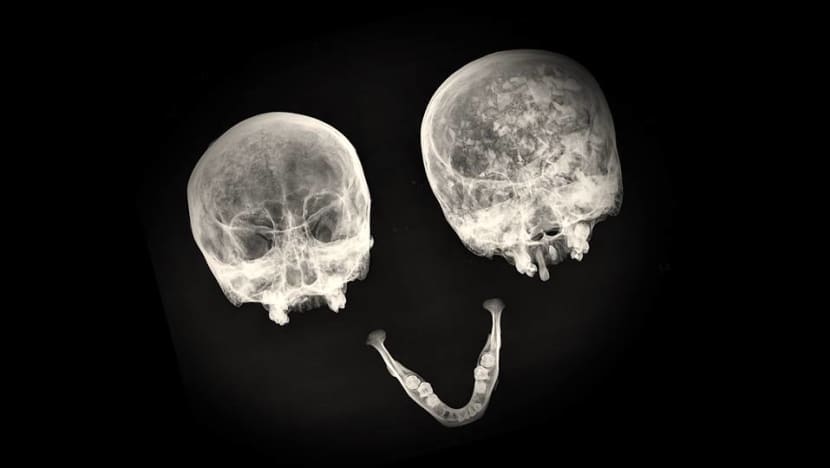

It “didn’t seem real” to Park, who could not recognise his child from the remains or the clothes. But the clothes were a match. The police also found the dental braces of one of the boys.

“We were filled with guilt. It was so depressing to realise what worthless parents we were,” says Kim. “We were unable to relieve the spirits of our children.”

It was two locals, hiking up a trail and collecting acorns, who discovered the bones when they came across some old clothes among the rocks. But something was strange.

One child’s remains, for example, were found with the trousers “flipped over his shoulders” and the sleeves “tied together”, describes Woo. When the knot was untied, empty cartridges and unused bullets were found.

Kim, the child’s father, had only one thought: “I was convinced that the children were shot.”

The police called forensic scientist Chae Jong-min, a professor at Kyungbook University, to the crime scene. But he arrived to find an “absurd situation”.

“The police weren’t specialists in excavating dead bodies. They just dug out whatever they could find. They didn’t know any better,” he says.

“The police were organising the long bones and the skulls together, which was ridiculous. An expert would’ve arranged the bones together as one complete body. So for around two to three hours, the police were making many mistakes.”

It was another heart-rending experience for Kim, who “had already cried so much by then”.

“How dare they treat the bones like this by arranging them in piles, then call us to look at them and ask (us) whether this is (our) child or not. We couldn’t do anything, so we became angry,” he says.

“The police have the law on their side. As parents, we had no power.”

At the time, there was also no system in South Korea to ensure that specialists, and not the police, excavated such remains, points out Chae.

WHAT CAUSED THEIR DEATHS?

The excavation was not the only thing the police were called out on, even by the media. A day after the remains were found, the police chief said hypothermia was “the most probable cause of death”.

Speaking at the scene, he told journalists that the lowest temperature recorded at that time was 3°C. “But when it rains in the morning, the wind chill factor would’ve lowered the temperature, and the bodies were huddled together,” he said.

This insistence that the children died of natural causes prompted a team from the Korea Alpine Federation, who are often called in for emergencies because of their experience in mountainous areas, to check the site.

They were certain it was not a hypothermia case. “That area isn’t high up at all. It isn’t even 100 metres from the streets. Just use some common sense,” says rescue team director Choi Won-seok.

“If it was cold and raining, it would’ve taken only five minutes to run home.”

The “strongest evidence” of foul play, according to Chae, was that “if a child died naturally, the bones would’ve been found on top of the dirt”.

“When a corpse is on top of the dirt, it rots or animals come and rip up the body, which means the bones would’ve been separated,” he says.

“However, the bones were all buried, which means that someone killed them and meticulously hid them. So we needed to figure out why, and we couldn’t.”

What was confirmed — by the 50th Infantry Division — was that the bullets found with the bodies were from its shooting range.

But the military insisted at a press conference that it had nothing to do with the deaths and that there was no drill that day, a public holiday.

“But there was one unusual detail,” says Park. “Commissioned officers could shoot on their own. So a typical soldier would’ve had a day off, but a commissioned officer could’ve come anytime and practised shooting.”

The shooting range was relocated to a nearby town in 1994, but a map at the time of the children’s disappearance showed that their remains were found “only 100 to 200 metres (away) … 300 metres at most”, says Choi.

That is within the effective range of the M-16 rifle, he points out, harbouring the same suspicions all these years.

“It was reported that an officer fired his rifle on that day in order to use up the leftover bullets,” he says. “The identity of the officer is still unknown.”

Chae’s forensic team could only examine the bones they excavated, and had to discount those dug out by the police as evidence. But they managed to find “sharp cuts” on the skulls — man-made injuries that occurred before the children’s deaths.

“One child had his clothes turned inside out, which could mean that the culprit covered his eyes with the clothes, then … murdered the children by hitting their heads with some type of weapon,” surmises Chae.

“Many experts assumed that this was done by a psychopath. And if it were a psychopath … there should’ve been other cases like this. But there’s never been a similar case, either before or after.”

SAYING GOODBYE

As speculation increased over the cause of death, the police reviewed all the case records from 1991. But the investigation fizzled out when they could not find more evidence.

So, two years after their remains were found — and stored in the university hospital morgue — the boys had their funeral at last. “At that moment … I finally realised that it was all real,” says Park.

“The hearse was covered with chrysanthemums. Somebody donated the flowers. I felt very grateful. At least we sent them away properly.”

The parents took the ashes to the Nakdong River so their children could “float away into the Pacific Ocean”, Woo says, his Iips quivering at the memory.

Park adds: “They died together, so we wanted them to play together in the afterlife.”

The parents’ lawyer, Kang Ji-won, filed a lawsuit against the police for having “not done their jobs properly” by, for example, botching evidence at the crime scene.

“We had three trials, and we lost them all … (The judges) didn’t arrive at any verdict that directly pinned the blame on the police. How can that be their final judgment?” he questions.

“The police or the government should’ve set up a comprehensive police investigation team. They should’ve tried to find out the cause — whether it involved the military base or not. They should’ve investigated further.”

He has a “conspiracy” theory to explain why they did not: It was still a “dangerous time” during President Roh’s military-backed rule, and power resided within a “rigid hierarchy”.

So the parents were left with only their own assumptions. Says Kim: “I think one child was killed due to an accidental shooting, and the rest of the boys were killed as well, to cover up the accident.”

No one has ever been arrested in connection with their deaths. In 2015, however, South Korea removed the statute of limitations for first-degree murder, which means any new evidence could lead the police to reopen the case.

“The statute of limitations (originally) was 15 years. But various people and activist groups raised objections,” says Kang.

“Because of the frog boys’ case and others, (South) Korea’s legal system has gradually advanced. We can still hope to uncover the truth.”

Woo vows to “keep searching for the criminal until the end”. “The police have changed a great deal. They have more advanced methods, and their thought process is different,” he adds.

“Back then, the police ignored us and treated us with disrespect. But now they’re more sympathetic, and they try to listen to us.”

It has been a long wait, however, for these men in their 60s and 70s. Park says: “My life is almost over anyway. I’ve been patient until now. I can wait a little longer to see (Chan-in).”

Nothing so far has healed their hurt. “(Yeong-gyu) was a good child,” says Kim. “Now that our children are all gone, I feel as if the sky’s falling. And my heart’s breaking.”

There is something Woo wrote to his boy, Cheol-won, and the other “lovely sons”. “It’s said that when your parents die, you bury them in the ground. But when your children die, you bury them in your heart,” he reads.

“I thought that I could forget you after seeing you return to dust, but I miss you even more as time goes by.”

Watch the CNA special, In Search Of The Frog Boys.