How poverty tends to trap people into making poor decisions

Weighed down by a scarcity mindset and tunnel vision, the poor are at risk of making choices that feed the poverty cycle. Sometimes they are out of options.

As experts told the programme Why It Matters, poverty is complex and is not only about not having enough money.

SINGAPORE: Every time her four children passed by the provision shop downstairs, they would ask her to buy packet drinks for them. Every time, Mdm Mary Yeo would reply, “No, not today.”

The first time the divorcee received financial assistance from the Social Service Office, her first thought as she sat at home alone, pondering what to do with the money, was their wistful request the night before.

“I rushed down to the provision shop, and I bought quite a lot of drinks,” said the 47-year-old. “The next day, I bought (more).”

After three days, she had bought S$400 worth of drinks — 40 cartons — “because that same thing kept coming” to mind.

“I just didn’t think of anything else,” said Mdm Yeo, who was left with about a third of the S$650 she was given. “It was quite scary … (I was) quite stressed.”

She did not know it then, but she was experiencing one of the common effects of poverty: A kind of tunnel vision that focused her mind on only one thing.

From being broke and seeing her children deprived of packet drinks, her mind started obsessing about what her family was missing.

As experts told the programme Why It Matters, poverty is complex and is not only about not having enough to buy the things that one needs, such as food, clothing and shelter.

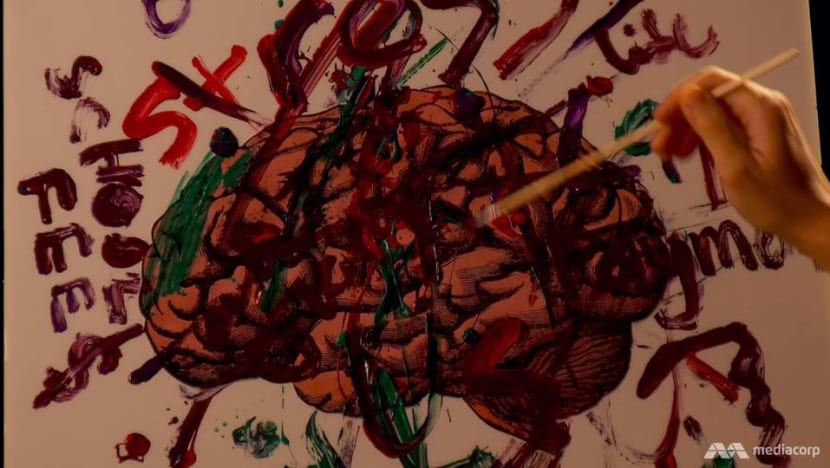

The problem of scarce resources has consequences that make long-term decision-making difficult, owing to what the financial stress does to the mind. Poverty even has biological effects.

While there are schemes in Singapore meant to help the needy get back on their feet, the odds are stacked against them in more ways than people imagine — and in ways that might require policy redesign.

WATCH: Why the poor are trapped into poor decisions (5:02)

POVERTY PLUNDERS PERSPECTIVE

Ask Singaporeans why poor people are poor, and the most likely answers are poor health, laziness and lack of higher education — at least, that was a finding of a Channel NewsAsia survey in July of 1,000 respondents on class divisions.

This attitude stems from a spirit of self-reliance — that in Singapore, people make their own luck, or bucks.

But when people have financial woes, there is more to consider. Owing to what is called the scarcity mindset, one’s attention gets consumed by immediate problems, and one’s best long-term interests are rarely considered.

And the more problems one has, the lower one’s bandwidth is, according to The Therapy Room director and principal psychologist Geraldine Tan. This means not strategising or analysing tasks well, which is more likely to result in inferior choices.

“When you’re stressed — a lot more negative emotions, which are very heavy — it might impede your cognitive functioning,” she explained.

“If you’re constantly bugged by having to think when the next meal is going to be on the table … the problem is compounded and perpetuated. It’s very hard to break out of it, and it affects their work.”

Dealing with bread-and-butter issues that one cannot solve may make a person anxious and frustrated or even depressed.

Many people, when faced with stressful situations, may go on their mobile phones or watch Netflix, but when the poor are distracted from what they need to do, they are seen as procrastinating or being lazy, said Ms Tan.

“It looks like an attitude problem, but it’s not an attitude problem because all these were happening, (which) we can’t visibly see.”

How much impact can having so little have? Research from Princeton University has claimed that the dip in cognitive function in a person preoccupied with money problems is similar to a 13-point drop in IQ.

IT CUTS BACK CHOICES

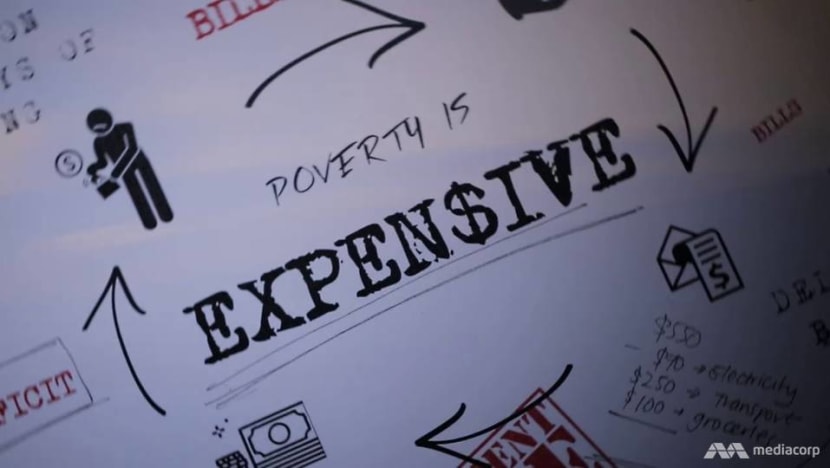

Being poor can also be expensive, which is a reality Mdm Noridah Abdul Rahman faces as she raises five children in a one-room rental flat on a single income of less than S$1,500 a month.

She receives S$420 from the Community Care Endowment Fund (ComCare), so when she goes grocery shopping, she ensures that she does not exceed her weekly budget of about S$100 for groceries.

In her case, it may not be a question of whether she is making the most of the financial assistance, but rather whether she can.

For example, she usually buys one pack of diapers to keep within the week’s budget, even though she could save about S$3 per pack by paying S$45.95 for two, instead of S$26.25 for one.

She is also losing out on grocery cashback deals, pointed out Ms Valerie Kor, an editor at MoneySmart, one of Singapore’s largest financial portals.

There is, for instance, the Bank of China (BOC) Sheng Siong card, which gives holders a 7 per cent cash rebate on in-store spending, while the POSB Everyday card offers a 5 per cent cashback with no minimum spending.

But as these are credit cards, the qualifying annual income is S$30,000. If Mdm Noridah had the BOC Sheng Siong card, she could save about S$35, assuming a monthly expenditure of S$500. That would cover one week of her rent.

Missing out on bulk buying, shopping discounts and cashback is just one example. Incurring penalties because of a backlog of bill payments, such as for utilities, is another fact of life for the poor.

The deficits pile up and spill over into the next month. The cycle continues, and so does the list of everyday situations where a cash shortage can create a shortage of choice.

For example, the Why It Matters producers asked two groups — those earning more than S$2,000 a month and those earning less — what they would do if their fridge broke down.

Those from the first group said they would decide within a day to buy a new fridge, with a budget of around S$1,000, for example, or just “the best kind of fridge for the best kind of money”.

Those from the other income group said they would have to wait for payday first, try to fix the fridge instead, or failing that, get the cheapest one available or a second-hand fridge.

When this group was asked what they would do for a sprained ankle, one person said he would “use a walking stick or something for support”, while another would use a “home remedy” because seeing a doctor is “very expensive”.

IT TAKES YEARS AWAY FROM LIFE

Through cycles of time, the effects of poverty can also be physiological. For example, National University of Singapore researchers have found that it is linked to ageing.

Based on a study of 1,158 undergraduates, Professor Richard Ebstein from the NUS Department of Psychology noted that the DNA of students here who were from a lower socio-economic class had shorter “telomeres” than those whose families had more money.

A telomere is a physical end of a chromosome, much like plastic tubes at the end of a shoelace that prevent it from unravelling.

“It’s the same function, essentially, that a telomere has: To kind of protect the end of a chromosome and prevent damage,” Prof Ebstein said, explaining that telomere length is an index of ageing.

“These students — and they’re healthy — are just ageing faster than other students.”

Hence the implications of poverty are long-term and may not manifest until adulthood.

“Even at 22 years old, if you’ve come from a poor background, and you’ve been accepted into NUS, you’re still a bit more stressed out and worn out, even though you’re successful in school,” he added.

“Poverty is not just (about) not having enough money. It has consequences for your actual physical and mental health.”

WHAT’S NEEDED: SECOND CHANCES

Financial assistance can ease conditions for the poor, and in Singapore, this comes in various forms, including public rental housing at subsidised rates, utilities grants, additional home ownership grants, child and student care subsidies and the Community Health Assistance Scheme.

From April last year to this March, about 79,500 Singaporeans received ComCare assistance for low-income households.

As the margin of error for people living on the margins tends to be slim, sociology professor Sulfikar Amir believes that only with a resilient social structure would the consequences of their mistakes not worsen their economic outlook.

The Nanyang Technological University associate professor suggests social policies should be designed in the same way airplane cockpits are designed with backups for engines and other critical safety equipment.

“We need to create a system that’s fully resilient. We should have this multi-layered defence mechanism in which, in a situation where one (policy) fails, there’s a backup to support the people who are affected by this policy,” he explained.

He cited a single mother needing to improve her skills but having to look after her two children: She would need more time to complete her lessons.

Public policy should be customised or tolerant of such situations, he said, in a way that buys the poor second chances.

The clash between going for skills development and attending to family matters was an example also given by Mr Aaron Yeoh, the founder of social enterprise Etch Empathy, which conducts poverty simulation exercises for schools and corporations.

He agreed that the social system must turn things around for the poor, who otherwise risk each slip-up becoming a series of more setbacks.

“It’s a long journey, so sometimes when the support isn’t there, and when the journey’s too tough for them, they might drop out halfway,” he said.

“Society could recognise that an unforeseen situation might happen. So if there’s more flexibility for them, that might help.”

Watch this episode of Why It Matters here.