Commentary: After an epic struggle with Higher Mother Tongue, maybe I will finally speak the language as an adult

Despite efforts to steer national education away from grades and exams, Higher Mother Tongue Language seems still tied to a transactional mindset around learning, says CNA’s Erin Low.

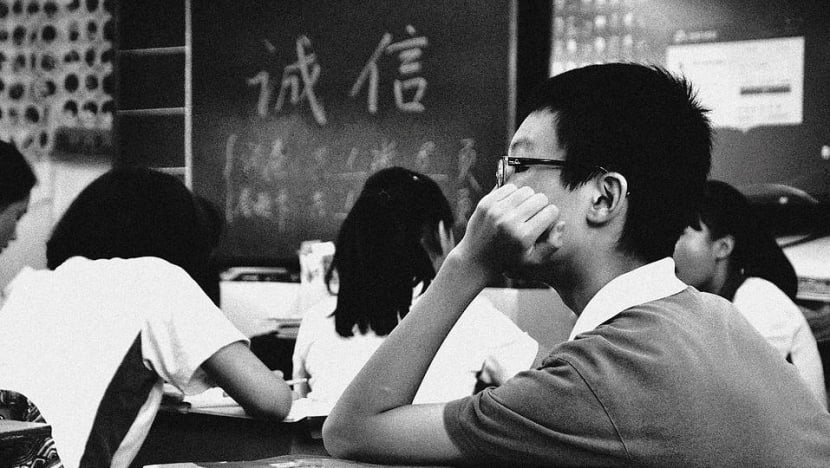

(Photo: Pixabay/ken19991210)

SINGAPORE: Even as working adults with school long behind us, my friends and I still commiserate about the sheer struggle that was Higher Mother Tongue Language (HMTL).

There were those who could pass each test with flying colours, by dint of growing up bilingual or having a natural affinity with languages.

I was blessed with neither. Just to keep afloat, I needed daily remedial, weekly tuition, holiday classes, assessment books, mock papers and non-stop immersion in Channel 8 dramas and mandopop.

Even now I still get nightmares about finding myself in exam halls staring down at a Chinese paper – and seeing only incomprehensible squiggles.

READ: Commentary: Raising bilingual children is challenging but immensely rewarding

TWEAKS TO THE SYSTEM

War stories like these might be par for the course – after all, HMTL is notoriously difficult and is meant for students who can handle the added workload.

This is probably why when a new Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE) scoring system kicked in this year, giving some the impression that it might be easier to take HMTL at the secondary school level, the Ministry of Education stressed there’s no change to the standards and assessment of PSLE.

READ: Indicative PSLE score ranges for all secondary schools released under new scoring system

But recent changes to HMTL curriculum, where children are being eased into HMTL earlier at a younger age, might help flatten the learning curve.

While all schools offer Higher Mother Tongue at Primary 5, Higher Chinese Language is increasingly available to Primary 3 students. Starting next year, Higher Malay Language and Higher Tamil Language will be available to Primary 3 students as well.

A TRANSACTIONAL MINDSET AROUND HMTL

These changes to encourage kids to take up languages at a challenging level reflect the larger shift in the education system towards imbuing a love for learning.

But sometimes mindsets can be the slowest to change. If today’s students are like me and my friends, taking HMTL may be less motivated by a love for languages but by practical benefits.

Students who pass Higher Chinese receive a posting advantage for admission into prestigious Special Assistance Plan (SAP) schools.

Students who pass HMTL at O-Levels enjoy a two-point deduction from their aggregate scores, and the added perk of not having to take H1 MTL at A-Levels should they choose to go to Junior College.

These payoffs might be one factor behind the growing popularity of HMTL. At the 2018 O-Levels, 31 per cent of Chinese language students took Higher Chinese, up by 5 percentage points in the past decade. That figure was 34 per cent, up from 12 per cent for Higher Tamil and 14 per cent, up 2 percentage points, for Higher Malay.

READ: Commentary: In English-speaking Singapore, children face huge challenges in mastering mother tongue

One can argue that the advantages HMTL confers are well-deserved; a fair exchange for students’ blood, sweat and tears. Students also strengthen their mastery of the language by studying it at an advanced level. The hope is that this skill is something they can use well into their adult years.

At an Apr 16 event hosted by the Tamil Language Learning and Promotion Committee (TLLPC), then Minister for Communications and Information S Iswaran emphasised the importance of cultivating a lifelong love for mother tongue languages. He said the opportunity to study Higher Tamil in Primary 3 and 4 will help sharpen language proficiency and deepen understanding at a younger age.

No doubt the formalised system of HMTL helps achieved this. But if we chase after HMTL only because of the grades and bonus points, then what is left to motivate us to speak our mother tongue when there aren’t incentives to score?

READ: Commentary: Learning another language has benefits - just not the economic kind

PART OF A PACKAGE DEAL

An unfortunate reality is that many students who took Higher Mother Tongue weren’t suited for the subject – including me. But we signed up anyway because HMTL was part of a package deal.

Take my friend for example. She had good enough grades to get “promoted” to the top Secondary 2 class. She just had to enrol in Higher Chinese.

Like many who take this route, the subject was an uphill battle for her. One day at class, their teacher pointedly remarked: “I don’t understand why some of you who are not up to standard insist on doing Higher Chinese.”

Maybe she was right – after all, HMTL is meant to be studied by students with the right interest and aptitude. Yet we clung onto this quid-pro-quo system of HMTL, taking it only to reap its dividends after O-Levels, or to get coveted spots in classes and schools.

A LIFELONG LOVE FOR MOTHER TONGUE

If we continue to harbour a utilitarian mindset around mother tongue, it’s no surprise when a student drops the language right after O-Levels. Most of us could hardly wait to wipe clean all the unpleasant memories associated with it.

That’s what many of my classmates did at junior college. With one subject in the bag, we spent afternoons hunkered down in the library doing homework or revising for other A-Level subjects, while the non-HMTL students toiled at H1 mother tongue class.

READ: Commentary: Forget uni for now. After the A-Levels, get work experience first

The need to cultivate that love for mother tongue is more urgent when more households are speaking English predominantly rather than their mother tongue.

According to Singapore’s 2020 census, English has become the language most frequently spoken in households. 48.3 per cent of residents speak English at home, up from 32.3 per cent in 2010.

Meanwhile, the proportion of residents who speak mother tongue languages at home has dwindled – 29.9 per cent of residents speak Mandarin; down from 35.6 per cent; 9.2 per cent speak Malay, down from 12.2 per cent; and 2.5 per cent speak Tamil, down from 3.3 per cent.

READ: Despite greater use of English, mother tongue languages still highly relevant: Language promotion councils

READ: Commentary: How I picked up the pieces after failing my A-Level exams

I remember my last conversation with my Higher Chinese teacher, which took place as she handed me my HMTL O-Level certificate. I scraped by with a C6 – the minimum passing grade.

She smiled wryly at me, knowing the pain I (and probably she too) endured just to get to that point.

“Promise me you’ll keep working,” she said. “Your journey with Chinese has only just begun.”

I cried in relief at having passed my hardest subject in school. It’s no surprise I never kept my promise to my teacher to keep at it – because the journey hurt so much.

But now that I’m not tied to the pressure of gaining bonus points or admission into a good school, I can be free to embark on learning the language. Just for the sheer interest in it.

(Listen to three working adults reveal how their PSLE results have shaped their life journeys in a no-holds barred conversation on CNA's Heart of the Matter podcast:)

Erin Low is Research Writer for the Commentary section. She also works on CNA podcasts Heart of the Matter and The Climate Conversations.