commentary Commentary

Commentary: Dear Indonesia, shaming the infected is a lousy COVID-19 plan

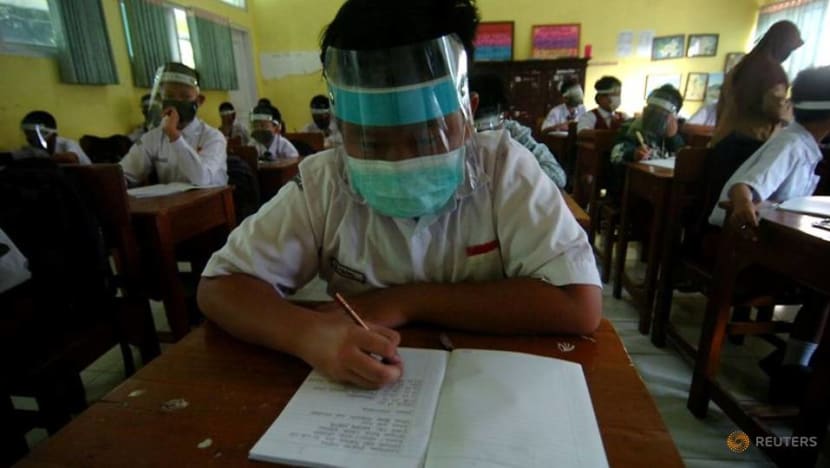

Breaking the cycle of shame will require strong leadership at the central and local levels, says ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute’s Made Supriatma.

Passengers wearing protective face masks queue for a public bus, following the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak, at a central bus spot in Jakarta, Indonesia on Jul 27, 2020. (Photo: REUTERS/Willy Kurniawan)

SINGAPORE: Imagine being a healthcare worker on the frontlines of fighting the deadly pandemic in a hospital, working endless days to help almost 100 patients each day on your own.

Imagine also battling your own fears of catching the virus, in a country with one of the highest COVID-19 death rates of healthcare workers.

And then imagine coming home to find out that other children in the neighbourhood refused to play with yours – because you work in hospitals and treat COVID-19 patients, and hearing parents tell their kids your family has been exposed and will transmit the virus to the community.

These tales are commonplace, according to Northern Jakarta’s Sulianti Saroso Hospital for Infectious Disease nurses who revealed their ordeal to local news outlets in April.

READ: Commentary: COVID-19 has killed some friendships - but that’s okay

READ: Commentary: Common sense lacking in a world of COVID-19

In Semarang, Central Java, that same month, the family of a healthcare worker who died from COVID-19 had difficulty burying her body.

Communities living around the cemetery refused the burial on grounds of fear of contracting the disease.

The fact that this nurse died as a result of treating COVID-19 patients did not move them from this unnerving stance.

In Solo, Central Java, some landlords refused to rent out houses and rooms to nurses working in hospitals that treat COVID-19 patients. This rejection has also occurred in several places in Indonesia and has not only happened to nurses but also doctors.

Further afield in Bali, news reports highlight public backlash against returning Indonesian migrant workers who have lost their jobs.

While the Indonesian government made quarantine arrangements at hotels, crowds of residents living near in their vicinity gathered near transporting buses in an attempt to turn them away, after concerns they could bring the virus back with them brewed.

THE COSTS OF STIGMA

While these incidents stigmatising Indonesians perceived to have contracted the virus and those who treat them were stories from April, scores more have persisted five months after throughout Indonesia.

Public fatigue with the flood of stories that show problematic attitudes about COVID-19 has seen this issue disappear from the national agenda, even though such sentiments continue to fester in Indonesian society.

While experts and government officials expect the passage of time would see this stigmatisation subside as people gain more knowledge of COVID-19 with public education efforts underway, such hopes seem unrealistically optimistic.

READ: Commentary: When COVID-19 symptoms last for months, recovery feels slow and strained

LISTEN: The COVID-19 vaccine will be the biggest product launch in history. Can we pull it off?

An August survey conducted by LaporCovid-19, a civil society group that aims to improve the transparency of information on this virus, showed a majority (55.8 per cent) of polled COVID-19 survivors disclosing they experienced various kinds of stigmatisation including social exclusion and even bullying on social media, where they were called names like “virus carrier” or “superspreader”.

The poll is particularly disconcerting when more than half of respondents were healthcare workers whose courage, determination and expertise are sorely needed in one of the most pressing periods in the country’s fight against a dangerous infectious disease. Indonesia has seen more than 3,000 daily new cases over the past week.

Meanwhile, over 100 Indonesian doctors have succumbed to COVID-19, according to the Indonesian Doctors’ Association, one of the highest in the world.

SHAMING OF COMMUNITIES

Targets of this shame extend beyond individuals to their families and even to their community.

In Jakarta, I met a neighbourhood association (a rukun tetangga) whose members were not allowed to visit other neighbourhood association areas because a member there had caught the virus.

Part of this fear is motivated by the prohibitive economic cost of catching the virus. If someone is infected, he or she and their close contacts must be isolated for 14 days, a burdensome isolation period few can afford when many lives depend on daily work.

People also point to the cost of testing which outweighs the daily wage of an Indonesian worker by many times at 375,000 rupiah (US$25.70) per person, when entire families will have to be tested when one person catches it.

This economic threat has created a crisis in society, facilitating the "othering" of coronavirus patients when precautionary behaviour aiming to separate the healthy from the infected incites suspicion and sows divisions.

READ: Commentary: Making sense of shifting goalposts in public policy and the science of COVID-19

READ: Commentary: That new problem of disposable masks ending up as trash on pavements and beaches

THE HIGH STAKES

What is also at stake is the risk that such public sentiments fuel a national health emergency.

While it is deeply troubling that prejudice, even discrimination, have come to characterise how Indonesians view the heroic victims of COVID-19, the worry is if such attitudes discourage those with symptoms to get tested and allow huge reservoirs of undiscovered infections to remain.

At about 200,000 total cases, one of the region’s highest, experts have cautioned that Indonesia’s testing rate, at less than 8,000 for every 1 million residents, remains one of the lowest in the world.

Its positive rate continues to persist at figures “far above” the World Health Organization's 5 per cent standard for countries that have flattened the curve and are ready to enter a “new normal” – at 14 per cent, according to COVID-19 taskforce spokesperson Dr Wiku Adisasmito.

Breaking this stigmatisation will require proactive government intervention and societal change.

It feels very long ago that the Indonesian government had initially administered free tests targetting essential workers, when both the central government and regional authorities worked hand-in-hand to get their act together to normalise testing.

Bali provincial authorities had provided free tests for drivers transporting goods to this region but discontinued this practice given the high costs that reportedly amounted to 2 billion rupiah each day.

In that vacuum, some logistics firms have reluctantly stepped in to bear the costs, which may unfortunately be reflected in higher consumer prices, but enforcement against businesses that flout health measures have been half-hearted and spotty.

READ: Commentary: Can Indonesia manage both COVID-19 and the looming threat of haze?

READ: Commentary: Indonesia’s half-hearted effort to halt massive Ramadan exodus is all form, no substance

This also points to the problem of moral hazard where businesses left to their own devices on testing workers may be incentivised to sidestep reporting cases altogether where the rules mandate that workers who have come into contact with a case must be tested and operations shut down for deep cleaning.

The trouble also is that the Indonesian government seems to be dithering in its overall national response in tackling the pandemic, seen in the patchy provisions of tests and inadequate contact tracing

This tepid reaction only adds to the uncertainty gripping the nation, feeds the notion that only individual action and self-reliance can counter the coronavirus spread and inadvertently bolsters the sense of stigma Indonesians confer on the sick.

Another way to overcome fear is to encourage civil society to come together. Some villages, like Cempluk in East Java, have developed mutual self-help systems to deal with this pandemic.

Volunteers help to distribute food and essential items so families can stay at home.

Instead of alienating community members who contracted the virus, village leaders and community members jettisoned those old mindsets to set good examples to care for villagers’ families, rice fields, gardens and livestock.

To be fair, resilience like this can only be built because some communities in Indonesia already have strong bonds and some level of social capital.

But in a country staring down the coronavirus at an inflexion point in its fight, it’s also small gestures of leadership like these that can make a sum difference in pulling communities together and ending the stigma.

LISTEN: What next for Malaysian workers stuck there and Singapore businesses who hire them here?

BOOKMARK THIS: Our comprehensive coverage of the coronavirus outbreak and its developments

Download our app or subscribe to our Telegram channel for the latest updates on the coronavirus outbreak: https://cna.asia/telegram

Made Supriatma is Visiting Fellow, ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore.