commentary Commentary

Commentary: Behind dashed hopes of Mandarin Gardens en bloc sale, unbridled speculation and wishful thinking

The promise of a collective sale agreement has artificially pushed up prices in developments, which are not sustainable, say NUS’ Chia Liu Ee and Sing Tien Foo.

Mandarin Gardens in Siglap.

SINGAPORE: Hailed as a bright spot in 2017, the strong recovery in the en bloc sector received a rude shock after the property market was slapped with a fresh round of property cooling measures in July 2018.

On the surface, the latest casualty of this sledgehammer were the more than 1,000 residential unit owners of Mandarin Gardens, who seemed to be making steady progress towards what would have been Singapore’s priciest collective sale agreement - until it came to a grinding halt last week, leaving many readers wondering whether the en bloc fever has finally cooled.

The 99-year leasehold condominium failed to garner enough signatures to start the tender process.

But there were warning signs the deal was already on shaky ground.

The Mandarin Gardens’ en bloc sales committee raised the asking price twice from an initial S$2.478 billion to S$2.788 billion, and then again to S$2.927 billion.

Despite the record-high asking price, the committee obtained only 68 per cent falling short of the requisite 80 per cent consensus, when the collective sale agreement expired.

DEVELOPERS ARE THINKING TWICE TOO

The residential private property market has softened considerably since the cooling measures were rolled out. More than 30 collective sale tenders have ended without successful bids.

The raised Additional Buyer’s Stamp Duty (ABSD) and tightened Loan-to-Value limits have increased transaction costs when residential properties change hands, making it deliberately painful especially for those thinking of buying a second or subsequent residential property for investment.

The additional ABSD imposed on developers snapping up land for en bloc redevelopment has also made it more costly if they fail to sell all units within five years.

These measures have already claimed their first victims in halting other en bloc projects – developer Tee Land called off Upper East Coast’s Teck Guan Ville’s collective sale in late July 2018 after redoing their sums, and Lafe Corp backed out from buying over Sophia Road’s Fairhaven in October 2018.

STOP, PAUSE, THINK

While many observers have highlighted the additional costs in terms of stamp duty and limits on loans imposed on buyers, sellers and developers, which have no doubt dampened the private property market, less talked about are the effects of the measures in cooling speculative sentiments and forcing these actors to think twice.

The effects of the ABSD measures on en bloc activities are two-fold. Owners of en bloc properties will have to pay a higher ABSD when purchasing a replacement property, and will therefore need a higher reserve price to be incentivised to move out and recoup their costs.

But a higher asking price will now put off developers who have to consider their additional ABSD costs as well as whether a high selling price will deter potential buyers facing additional hurdles. Developers, in thinking about en bloc acquisitions, face a double whammy of a non-remissible ABSD and dwindling demand as local and foreign buyers are more cautious.

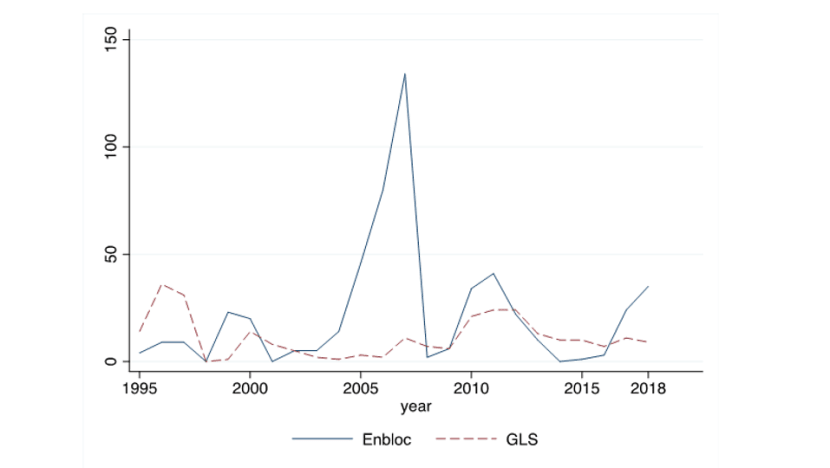

EN BLOC FEVERS OVER THE LAST 20 YEARS

The fact is land demand in the private property market had been relatively sanguine in the 1990s. An en bloc frenzy broke out in the early 2000s but was cooled quickly by the US subprime crisis in 2007. This external shock put the world in a grave economic crisis and killed demand, as banks and governments struggled to stimulate their economies.

But as market sentiment picked up, reaching another fever pitch in 2011, the Government stepped in to cool speculation by introducing ABSD for the first time, targeting foreigners and corporate entities, as well as Singaporeans buying for investment purposes.

But as land banks were drawn down over the last six years, and the market got accustomed to factoring in ABSD costs, developers started sniffing around to acquire land in late 2016 and the en bloc market picked up.

SPECULATIVE EFFECTS IN EN BLOC PROPERTIES

The fact is that en bloc sales artificially push up the prices of apartments in a development.

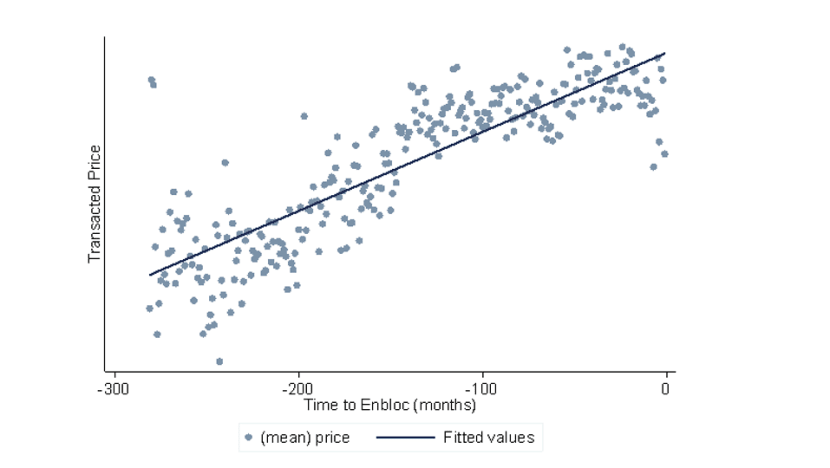

We have examined transaction prices of private properties for over 20 years. In our study spanning January 1995 to August 2018, we have seen a consistent pattern of prices rising over the year leading up to the en bloc sale.

In particular, compared to transactions occurring more than a year from the en bloc date, transactions in the three months leading to the en bloc date command a 15 per cent premium on average.

The road to a successful en bloc sales is long and winding from the setting-up of a collective sale committee, appointing consultants, and soliciting consensus from residents. However, the effects of an anticipated en bloc may be enough to stir demand, without the development reaching a collective sale.

THE EN BLOC PREMIUM

In our decades-long study of property prices, we matched properties sold en bloc with those that do not have plans for an en bloc sale and are similar in characteristics – including property age, distance to MRT, distance to primary schools and other location attributes – and found a significant difference in transacted prices of 5.4 per cent.

The results imply that the mere anticipation of an en bloc sale could trigger increases in both volume and price in resale activities in these developments. The effects are stronger closer to the en bloc date.

Speculators drive transactions occurring closer to the en bloc dates. Most are willing to pay higher prices and bear the risks the collective sale deal may not go through. They also incur seller’s stamp duty if en bloc deals are concluded within three years from their purchase dates. Many buyers become activist residents who proactively persuade other residents to support the en bloc proposition.

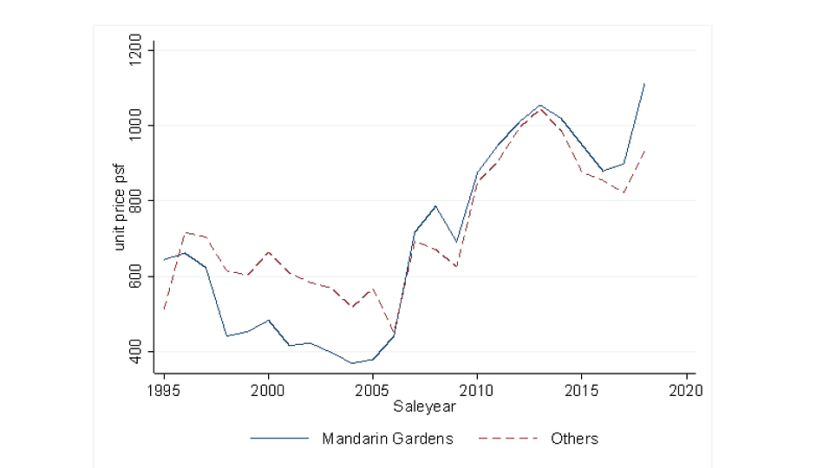

But the promise of an en bloc has a dark underbelly – as residents are hit harder with the introduction of cooling measures. When the 2011 cooling measures were imposed, en bloc properties suffered a steeper decline of 3.8 per cent in average resale transacted prices compared to non-en bloc properties.

THE EN BLOC FACTOR IN MANDARIN GARDENS SALE PRICE

A similar story looms behind Mandarin Gardens. When a first en bloc sale attempt was made in 2008, apartments in Mandarin Gardens started transacting at higher average prices than other properties in surrounding non-en bloc projects, suggesting significant anticipatory, speculative effects.

The development is an attractive candidate for en bloc – it has a low existing built-up plot ratio of 1.4. An almost double permissible plot ratio of 2.8 suggests redevelopment can be a handsomely profitable exercise.

But its large plot size could be a hindrance to a successful sale, as the number of owners the collective sale committee has to persuade is relatively large. In fact, our study has shown that the probability of en bloc decreases by 0.02 per cent with each additional apartment unit in a development.

Part of this arises also because large en bloc sites are also more difficult to sell, as they attract a small group of interested developers with strong financial backing.

ENDING THE EN BLOC FRENZY

En bloc redevelopments drive the urban renewal process in land-scarce Singapore. Old and under-developed properties are demolished and redeveloped into higher density properties.

READ: What happens when the en bloc musical chairs stop? A commentary

2018 marks the most eventful year for the en bloc market after the last two bouts of en bloc fever in 2007 and 2011. Strong en bloc sale activities coupled with record-breaking transaction prices risked spill-over effects into the residential property market and excessive price inflation.

The new ABSD rates imposed in July 2018 brought the en bloc frenzy emerging in 2017 to an abrupt halt leaving many hopefuls with a bleak outlook of finding potential buyers.

But the game of musical chairs isn’t quite over.

Far from it – though the beat might not be as fast-paced, the slowdown in the en bloc market provides a chance for developers, property owners, and even speculators to rethink their private property purchases, to shape a more sustainable residential private property redevelopment process.

Chia Liu Ee is a researcher and Associate Professor Sing Tien Foo is the Dean’s Chair and the Director at the Institute of Real Estate and Urban Studies (IREUS), National University of Singapore.