commentary Commentary

Commentary: Xi Jinping’s not-so-bad, actually-quite-good year in 2020

The Chinese President made several political moves last year to strengthen his power, says Christian Le Miere.

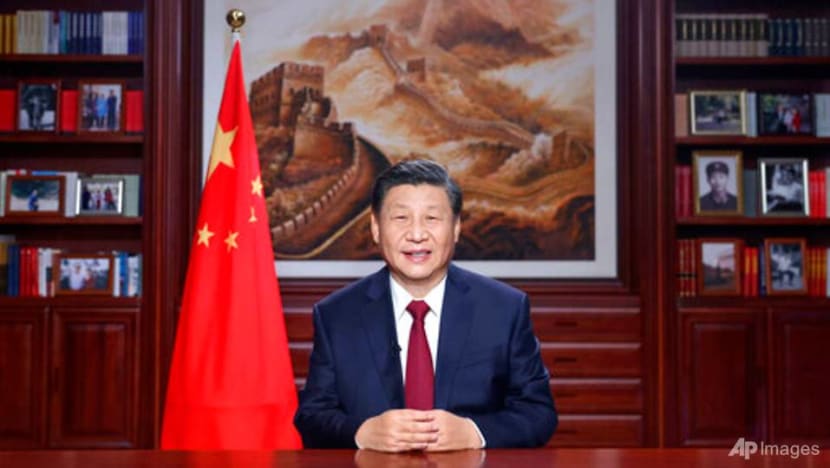

Chinese President Xi Jinping delivers a New Year's address in Beijing, Dec 31, 2020. (Photo: Ju Peng/Xinhua via AP)

LONDON: Many of us will look back on 2020 with anger as a year filled with illness, loss, penury and tragedy.

But one man may see the year in a brighter light – Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Despite the start of the year looking dreadful for China, with a raging pandemic in Wuhan that threatened to overwhelm the country, by the end of 2020, it had emerged as the only G20 economy expected to see economic growth, with the virus far less virulent than in many Western countries.

The situation has led to a surge in self-confidence about China’s place in the world and the relative decline of the US after four turbulent years of the Trump administration.

What’s more, just as after the global financial crisis of 2008 to 2009, the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic appears to have furthered the nationalistic view in Beijing that its top-down, heavy-handed capitalist model is superior to the messier, more liberal Western political-economic models.

READ: Commentary: US-China relations - age of engagement comes to a close

READ: Commentary: Trump’s playbook on China in the South China Sea has some lessons for the Biden administration

Beyond China’s response to the pandemic, however, Xi also used this year to secure his own political position. To this end, throughout 2020, Xi has moved to reshuffle leading political figures, particularly 10 provincial party secretaries.

SHUFFLING PROVINCIAL PARTY SECRETARIES

Provincial party secretaries are the most powerful individuals in the political architecture of each of China’s 31 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions.

They head up the Chinese Communist Party within each province, which given the primacy of the party over state bureaucracy, effectively means they outrank the governors of each province.

The latest appointed party secretaries were Yin Li in Fujian province and Shen Xiaoming in Hainan. Both were previously provincial governors. Both are medical professionals and technocrats.

Xi has a habit of promoting technocrats, often with little political experience, into senior provincial positions, with several party secretaries and governors having been executives in the aerospace and defence industrial base, such as Zhang Qingwei in Heilongjiang.

Promoting medical experts in the wake of a pandemic looks like sensible politics, demonstrating the importance the government places on the medical profession at this time. But more importantly for Xi, it also elevates younger members of the party – Yin Li is just 58 and he replaced the 65-year-old Yu Weiguo.

Age is an extremely important variable in Chinese politics as there are unofficial and official mandatory retirement ages for cadres at various levels of the party.

READ: Commentary: They already have jet bombers and super missiles. Will Chinese fighter jets be more powerful than America’s soon?

Since 1982, the party has institutionalised retirement ages for for party secretaries, governors and ministers - currently set at 65 - and for deputy party secretaries, vice-ministers and vice-governors at 60.

Perhaps more importantly for Xi, there is an unofficial rule for the Politburo – the “qishang baxia” (“seven up, eight down”) rule – that states that those aged 68 or over should step down from the body, an unofficial norm that has been held since 2002.

This means that of the 25 members of the Politburo currently seated, 13 will theoretically step down in 2022 at the next National Party Congress.

BUILDING POLITICAL CAPITAL

As such, Xi is placing younger individuals in key provincial roles in order to ensure there are eligible candidates ripe for promotion. They will be politically indebted or connected to Xi.

Although it is not certain that Yin will be promoted to the Politburo, if he is elevated, he can serve two terms on the Politburo until 2032, and owes his entire political career to Xi, having only entered politics five years ago.

Similarly, in November, four other provincial party secretaries were reshuffled – Jing Junhai was moved into the post in Jilin, Xu Dazhe in Hunan, Ruan Chengfa in Yunnan and Shen Yiqin in Guizhou. Xu was one of the aerospace executives who had been parachuted into a ministerial role in 2013.

Jing, meanwhile, is currently 60 and therefore young enough to serve in the next Politburo; he is also a native of Shaanxi province, having served much of his career in the province where Xi Jinping’s father was born and where Xi spent his most formative years as a sent-down youth.

Some of Xi’s closest political allies are natives and ancestral descendants of Shaanxi or spent time there, including Vice-President Wang Qishan and Secretary of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection Zhao Leji.

READ: Commentary: Can the world benefit from China’s economic resilience yet again?

READ: Commentary: Parts of Asia will miss Donald Trump’s tough China policy

Finally, through her promotion, Shen Yiqin became the only serving female party provincial secretary, putting her in a strong position to replace the retiring Sun Chunlan in 2022, who is currently the only woman on the Politburo.

Shen is also from the Bai ethnic minority, so if promoted, she would become only the fourth ethnic minority in history to serve on the Politburo.

CONSOLIDATING POLITICAL POWER

All of these changes point to Xi’s strategy to ensure a continued strong political network at the highest echelons of the party once the new Politburo sits from the end of 2022.

But they also indicate that Xi seems unwilling to abide by the unofficial retirement rules himself. He will be 69 by the end of 2022 and should by convention be retiring from his party roles, although this has been in doubt since the parliament removed term limits for the presidency in March 2018.

READ: Commentary: China’s spat with Jack Ma is a push to control Big Tech. Silicon Valley may be next

Now, another recent promotion further suggests his desire for continued political longevity. In November, Meng Xiangfeng was promoted to deputy director of the Chinese Communist Party’s Central Office and in line to replace Ding Xuexiang, one of Xi’s closest allies.

Ding may be promoted further to the Politburo Standing Committee, leaving Meng able to assume his role as effective chief of staff to Xi and a seat on the Politburo.

In the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, a stable and strong leadership may not be seen as a negative outcome for China.

However, the consolidation of power under Xi brings with it its own risks. Unlike his last two predecessors, Xi has failed to appoint any successors or heirs apparent and has centralised decision making around himself.

This means that should any further crisis befall China, the responsibility will lie primarily with Xi. Should anything happen to the man himself, there is no clear process for his successor.

This introduces an inherent fragility to the political system, which already struggles to react flexibly to any widespread discontent.

A centralised decision-making structure also makes it more difficult to have dissenting voices, which can at times stifle creativity and innovation.

The disappearance of Alibaba co-founder Jack Ma, one of China’s wealthiest and internationally most recognisable people, since late 2020 is a clear indication of this risk.

READ: Commentary: China dreams of being a tech superpower. Will that come true?

READ: Commentary: Closing door to Chinese students in US universities achieves little, only creates more tension

Ma, who reportedly ruffled feathers with his overt criticism of Beijing’s regulatory regime just before what was set to be Ant Group’s record-setting IPO, has not been seen since November.

The Wall Street Journal reported that Xi personally scuttled Ant Group’s IPO, indicating the dangers inherent when even the most influential businesspeople get on Xi’s bad side.

The lingering effects of such a move will be to ensure greater party control over business, but also potentially limit risk-taking by the capitalist elite in China.

Despite these risks of a personality-driven political system, Xi continues to centralise power around himself and reinforce his political position through promotion of his allies.

Thus, for Xi, 2020 started so very poorly but in the end brought a further consolidation of his position. The question is whether this might have a future cost in 2021 or beyond.

Christian Le Miere is a foreign policy adviser and the founder and managing director of Arcipel, a strategic advisory firm based in London.