Defiantly, he weaves life into a dying Peranakan craft

Heath Yeo quit designing modern fashion to revive the art of embroidering sarong kebayas the ‘old-fashioned’ way. But is it a losing battle against commercialism?

Kebaya maker and sulam embroiderer Heath Yeo in his workshop, cutting out pieces of fabric for a new kebaya. (Photo: Lam Shushan)

Heath Yeo quit designing modern fashion to revive the art of embroidering sarong kebayas the ‘old-fashioned’ way. But is it a losing battle against commercialism?

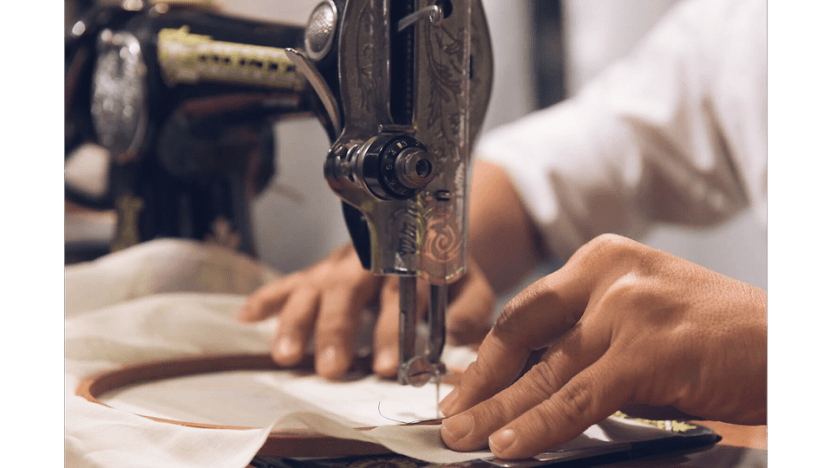

SINGAPORE: As he brushes his fingers against the soft voile and drapes it across her, he runs his right hand along her curves and grabs her firmly. Taking a deep breath, he moves in a steady rhythm as he presses down hard on the foot pedal of his vintage treadle sewing machine.

For Heath Yeo, time spent with her - the pronoun he bestows on his beloved sewing machine - is “like therapy”. When he is parted from her, his clumsy alter ego takes over - while walking across, he trips over his own foot and drops an entire box of pins on the carpet.

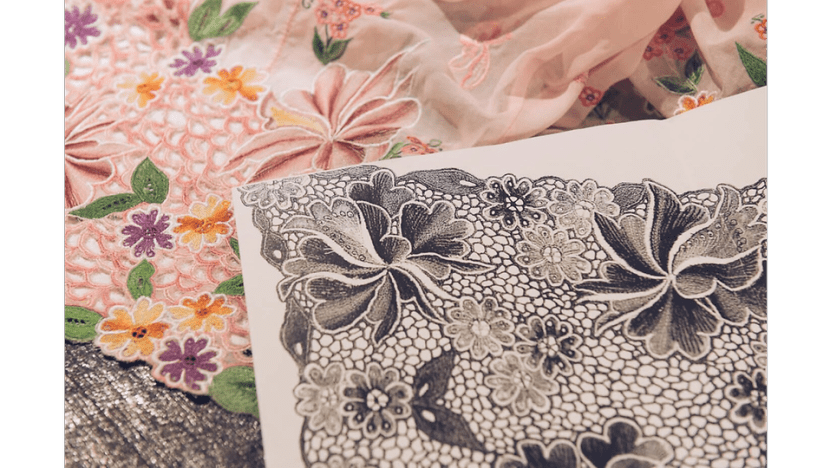

But once he begins sewing, a trance-like intensity falls over him. “Small, controlled movements left and right, this is how you do a satin stitch,” he says as his hands guide the fabric past the needle, lifelike flowers on vines taking shape and coiling up the cloth.

The 45-year-old is part of a dwindling pool of sarong kebaya makers in Singapore who still use the 1950s style of free motion embroidery - locally known as sulam - when sewing patterns onto kebayas, the traditional dress of Peranakan women. The tropical topography of Southeast Asia infuses his patterns, from the wavy petals of hibiscus flowers to the bold colours of native birds.

“People say: ‘It's just a machine, why are you so passionate about it?’ I think it’s because this humble machine can create things like these,” he says, pointing to an elaborately embroidered piece of fabric.

Mr Yeo laments that modern-day Peranakan embroidery is mostly done using electric machines. While the process can be computerised and completed in a fraction of the time that it takes him, such machines just do not impart the same intangible quality.

This human touch is what his old-time customers from the Peranakan community call “hidup” - which means “alive” in Malay. It takes just one look at Mr Yeo’s creations to grasp what they mean, and why these afficionadoes are willing to fork out anywhere between S$1,000 and S$1,300 for one of his sulam kebayas.

“That is very encouraging for me. It's the reason I do not want to go down the commercial route,” he says.

“It's like drawing or a painting... just that my canvas is that piece of plain cloth and instead of using water colour, I use a thread and needle to paint out my landscape,” he says.

He adds:“My sifu (teacher) taught me to go out and look at nature, to study how flowers grow. I noticed that if you try to follow the natural way they grow, it somehow appears on the embroidery as more three-dimensional, more alive.”

This sifu was the late Madam Moi of Kim Seng Kebaya, who got Mr Yeo hooked on the craft.

In the early 1990s, Mr Yeo was doing his national service in the SAF Music and Drama Company. He worked with Mdm Moi on a few kebayas for a play. She was fond of him, and wanted a successor to pass on her skills to, so she asked him to be her apprentice.

But Mr Yeo had bigger dreams - to make it to the runways of high street fashion. “I was young, maybe too ambitious, and really just not interested in traditional arts,” he says.

After graduating with a diploma in fashion from Lasalle College of the Arts in 1994, he devoted the next decade of his life to the formalwear industry, designing evening gowns and bridal wear for a Singapore brand.

“After learning about the different types of embroidery, I began to fall in love with this form of art. I said: 'Oh dear, I wonder who is working on embroidery using the good old traditional method?'”

He went back to Mdm Moi, by then in her late 70s, and begged her to give him a second chance as her student. She agreed grudgingly. But after a few months, it became clear that the young man she once wanted as an apprentice was, at last, ready to learn.

“She saw me put in the effort, so she started to share more about her thought and design process. She sat beside me as I sewed, teaching me how to use the machine, checking on my tension, checking the thread, and I was like a sponge - because I had limited time to soak up as much as possible,” he says.

Even as Mdm Moi’s health deteriorated over the next two and a half years, he recounts: “She went from being a teacher to a mother. We would chat after class and she would even cook for me.”

“The beautiful part was during the last few months before she passed, when she was in pain, she still made me show her my work, and she would correct my colour usage and shading to make the embroidery look more alive,” he says.

“She said to me: ‘I will go when you have learnt everything.’”

“She is someone that I will remember forever.”

LOSING TO CHEAPER ALTERNATIVES

Left on his own after her death, Mr Yeo felt the duty to put her legacy to use.

He says: “There seemed to be no one else equipped with this set of skills except for the very old ladies who were retired. That was when I plucked up my courage to start my little design workshop.”

But his plan hit snags from the moment he started out with a retail space at the swanky Tudor Court.

“I knew it was a niche market, but I did a bit of market study before I jumped into it, so I really thought there would be a handful that would support this industry,” he says.

He thought that his kebayas would appeal to working women looking for formalwear alternatives. But he quickly realised that unlike in his sifu’s time, when ladies had kebayas made for different occasions, the present-day woman no longer “fills her wardrobe” with kebayas.

Instead, the biggest supporters of his work are women in their 70s or older, some of them his former sifu’s clients - the generation that exclusively wore sulam kebayas made his way.

Faced with high rentals, as well as stiff competition from mass-produced kebayas that cost a tenth of his prices, he decided after three years that he could not carry on. “I lost out on many clients who chose to go for something more affordable because they did not understand the type of work I do.”

Still, he refuses to let go. While juggling his full-time job as a community worker, he makes kebayas in his spare time for loyal customers, in his current workshop - a backroom of his friend’s flower shop in Joo Chiat, leased for free to him out of goodwill. He even conducts workshops on kebaya making, hoping one day to find his own successor.

“My friends told me not to give up… and I cannot let go of this because it is something that is so part of our culture. It is our way of making,” he says.

END OF AN ERA, OR JUST CULTURAL EVOLUTION?

Not everyone, however, feels the need to cling on obsessively out of nostalgia.

In fact Mr Peter Lee, an author and expert on the evolution of Peranakan culture, points out that Mr Yeo’s free-motion method of embroidery is actually relatively recent in the history of kebaya-making.

Mr Lee explains: “The kebayas of the 19th century were different - my grandmother grew up wearing kebaya panjang (a longer version of the kebaya) and before the war, kebayas were hand-embroidered.” That is, no machines involved.

It was only in the first few decades of the 20th century that shorter versions of the kebaya started to become popular. Then, after the Second World War, the treadle sewing machine arrived in Southeast Asia, and what we know today as the “traditional” method of kebaya-making began to blossom, according to Mr Lee.

“So (free motion) embroidery on kebayas is just the most recent phase in an ongoing fashion evolution that went on for a couple of hundred years. A lot of the new work today is still strongly referencing the 1950s style. Is that good or bad? It just has not creatively progressed,” he says.

“The important thing is to keep it in the popular consciousness. People will adapt… we don’t need to cling on to tradition.”

Indeed, global clothing labels have been drawing inspiration from South-east Asian style. European fashion label Diane Von Furstenberg has released a line of jackets resembling the lace kebaya, while Uniqlo this year launched their Batik Motif Collection in collaboration with a popular Indonesian designer.

Says Mr Lee: “We need to abandon the idea of culture as something static. Peranakans have been around for 300 to 400 years, and every generation has been totally different. Real culture and real life involves a lot of change - and things need to change because it is an expression of the next generation.”

THE SPIRIT OF THE CRAFT

But for makers like Mr Yeo, that very idea of change is the antithesis of what he set out to do.

“I am fashion trained, so it’s very easy for me to pick up trends and to redesign these motifs into modern fashion,” he says. “But I decided that if I wanted to hold on to this tradition and heritage, I should do it the nice old way.”

As our interview draws to a close, Mr Yeo realises that he is late for his next appointment. He gets up and frantically starts folding up his fabric, gathering his measuring tape, scissors and dozens of spools of thread, and somehow manages to squeeze everything into his duffel bag, like a magical Mary Poppins bag.

Then with great care, he disassembles his beloved Singer sewing machine, covers her up with a piece of cloth, and tucks her away neatly.

When he leaves, I take a walk around the Joo Chiat neighbourhood where streets are lined with rows of Peranakan-style shophouses. I notice the fresh coats of pastel blue and pink paint, the antique tiles with cracks patched up, and groups of tourists holding maps navigating the heritage trail.

Perhaps there is no better place for Mr Yeo to be in than this Peranakan hub of Singapore, where there is a concerted effort at preserving culture. It reminds me of Mr Yeo’s words: “It's not about chasing after the mass crowd, but really, keeping the spirit of this craft alive.”

This is the third in a series of stories about Singapore makers, the craftsmen who are keeping artisan skills alive. Read our first story about a young bespoke shoemaker and our second story on an unassuming flute-maker who is sought after in China.

Follow @shushanlam on Twitter or CNAInsider on Instagram.