How this NUH expert makes artificial eyes to help patients be seen in a different light

NUH ocularist Suriya Abu Waled with an artificial eye, or ocular prosthesis. (Photo: Calvin Oh)

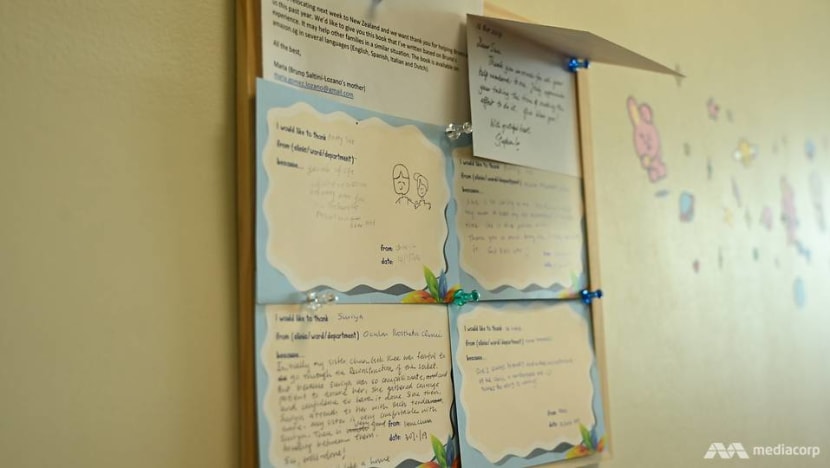

SINGAPORE: For those who have lost one or both of their eyes, the work of the only ocularist at the National University Hospital (NUH) gives hope and confidence, allowing patients to avoid the stares of others.

Armed with a steady hand and an attention to detail, Ms Suriya Abu Waled makes ocular prostheses, or artificial eyes, for about 15 new patients every year. She has worked in the hospital for 16 years, 14 of them as an ocularist.

"I love the job because I can help patients to regain their confidence and also to get trust (from others) and lead their normal lives," she said, speaking to journalists in an interview on Friday (Dec 18).

When an artificial eye is fitted in the socket of patients, it can even replicate some of the movement of a real eye, said Dr Gangadhara Sundar, head and senior consultant of orbit and oculofacial surgery in NUH’s department of ophthalmology.

“When the eyes are removed, the eye socket is replaced with an implant which is usually attached to the patient's eye muscles. Thus when the other eye moves, the implant moves, this in turn transfers the movement to the eye prosthesis, although not as perfectly or equally as the normal eye,” he added.

An artificial eye costs about S$2,000 for Singaporean patients and S$2,500 for foreigners. Ms Suriya also recommends that patients come in for polishing about once a year, with each session at S$100.

Each eye prosthesis takes about three to four days to make, she added, with a thorough process that involves making several models and hand painting the finer details of the eye.

Making eye prostheses is "an art and a science", said Ms Suriya, who trained in India for two months to become an ocularist. She was previously an imaging specialist with the ophthalmology department.

"You need to have a deep empathy for patients, great patience and also an eye for detail.

"They usually want to look their best for them. We understand because as a provider, I want them to be happy and feel comfortable wearing the prosthesis, so that when they walk out of my door, they feel happy to meet people and to see themselves (look) so natural. That is our aim."

WHO NEEDS A PROSTHESIS?

Aside from helping return patients’ lives to normal, a good fitting prosthesis is important to prevent sunken deformities in and around the socket after the eye is removed in a process known as enucleation, said Dr Sundar.

It also helps to preserve and restore the orbital structure and function in anophthalmic sockets, or an eye socket that is missing an eyeball but has the orbital soft tissues and eyelid structures.

Patients may lose their eyes for many reasons, including eye cancer, eye injuries, and occasionally failed eye surgeries, he added.

When attempts to save an eye fail, patients often “seek relief” from the pain and disfiguration, by opting for removing their eyeballs and replacing it with an implant in the eye socket. An ocular prosthesis is then placed to restore patients to “their structural, aesthetic and psychosocial normal status”, said Dr Sundar.

Ms Suriya has seen patients as young as 18 months old, and as old as 85 years old. One patient who has benefited from Ms Suriya’s work is Claire Lim.

The 10-year-old was diagnosed with persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous, a random or sporadic developmental abnormality that usually appears in just one eye, when she was in pre-school, said Dr Sundar.

If not treated very aggressively and early, the condition may result in other complications, he added. Thus, while it was difficult to restore Claire’s vision, doctors at NUH opted for an artificial eye.

But since she had a very “sensitive” cornea, doctors had to first use her own tissues to cover the cornea. After she recovered from the surgery, she was fitted for an eye prosthesis and has used one ever since, said Dr Sundar.

“It was really painful when she had to push the eye in. It feels like stepping on Lego,” said Claire, describing her experience with getting fitted for a prosthesis by Ms Suriya.

“A few hours later it was ok, but it was painful for a few minutes later. And I cried.”

Claire does not remove the prosthesis, although it occasionally drops out. She also has to use eyedrops three times a day. “Because she said it’s hard to take it out and hard to put it back in so I’m not going to go through the pain again.”

Claire’s father, Mr Lim Sze Liat said his daughter seems to feel more confident now, compared to in pre-school, before she started wearing the fake eye.

“She wouldn’t want to go to school, wouldn’t want to face her friends. Sometimes she would throw tantrums here and there,” he added. When she went to school without the prosthesis, one eye would be completely white, which attracted stares from classmates and teachers.

“But when she got her prosthesis and she walked about in school, people found that Claire looks normal. So everybody tried to play with her. Teachers also noticed she was more confident (after that) in kindergarten, which was where she suffered the most.”

HOW IT’S MADE

The patient is usually around for the whole process of making an ocular prosthesis. The first step is taking an impression of the patient's eye socket. An alginate solution is first injected into the eye socket using a syringe. After it hardens, it is removed from the eye socket and used to make the impression mould.

The next step is making a wax model. Wax is poured into the impression, and after it hardens, the model is inserted into the patient's eye.

Ms Suriya makes markings on the wax model to indicate where the patient's iris should be, and adjusts the model based on the patient's eye movements when they look around or open and close their eyes. There is also a pin in the wax model to indicate the natural direction of the iris.

Using the wax model, she then builds an acrylic shell around the iris button that forms the rest of the ocular prosthesis, or the eye whites.

Once the acrylic is cured, the first version of the eye prosthesis emerges. Ms Suriya then spends some time filing and buffing the iris button to make sure the size matches the patient's other eye.

The patient is then fitted with the acrylic eye prosthesis. At this point, Ms Suriya checks if the patient feels comfortable with the prosthesis, and whether any modifications to the size of the iris is needed.

Then comes the part that is more art than science. Using pigments and a tiny brush, she hand paints the iris to make it look as natural as possible, matching the patient's other eye.

She also uses thin red threads to mimic the look of blood vessels in the scleral, or eye whites. After putting the finishing touches on the prosthesis, she seals it all in with a clear acrylic mix with monomers, and the acrylic eye is cured again.

The final step is polishing the prosthesis, to make it shiny and glossy. The patient receives the eye prosthesis and the process is complete.

Ms Suriya said: “If the outcome is nice, is good, and the patient is comfortable and happy with it, of course it makes you so happy when you see the patient and (you’ve given) them self-confidence."