Meet the fake news trolls who influenced US and Indonesian polls for money

They have popped up in election campaigns from the United States to Malaysia to Indonesia. A small town in Europe was even dubbed the world's fake news capital.

In 2016, more than 100 pro-Donald Trump websites were being run from one town in Macedonia.

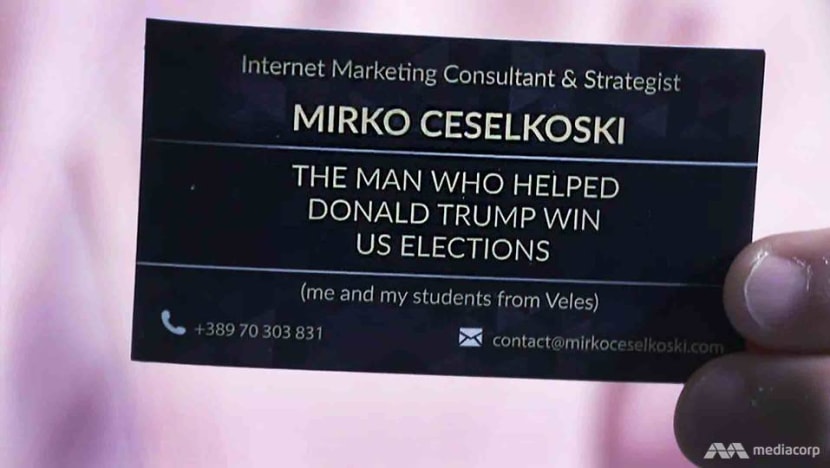

VELES, Macedonia: His business card states, “The man who helped Donald Trump win US elections”, and Mr Mirko Ceselkoski is eager to read it out, saying: “It’s so funny that I became famous because of this.”

Whether it was fame or infamy, the 38-year-old, who calls himself an internet marketing consultant, found a golden ticket not only for himself, but also the Macedonian town of Veles, where he had some students.

In 2016, more than 100 pro-Trump websites were being run from this town of 44,000 people, but not out of interest in American politics. The sites were hosting fake news for profit.

“The top performing (sites) were either really misleading or 100 per cent false,” recalls Buzzfeed News media editor Craig Silverman, the first to find this out after he and a colleague started their investigation that summer.

Veles became known as the fake news capital of the world. And since then, fake news industries have begun to make their presence felt in elections elsewhere.

That includes Malaysia and Indonesia, as Channel NewsAsia finds out in The Truth About Fake News, a special on who has been peddling falsehoods, the impact, and issues at the heart of the problem.

THE MACEDONIAN TROLLS

In the United States elections, Russian trolls might have faked news for political influence, but in one of Europe’s poorest countries, Macedonia, where the average person made about S$580 a month, the trolls had a simpler motive: Easy money.

Some factories in Veles had been shuttered, causing unemployment, and job opportunities were scarce. Fake news became a way for youths to make a living, and Mr Ceselkoski is happy that his “tremendously hard-working” students achieved success.

“When some of (them) started experimenting with US politics, the results were crazily good,” he says. “Many of my students were making more than US$100,000 per month. Many other students were doing great numbers – lower but still great.”

According to “Sasha”, one of the trolls, it began with a small group, and then it spread. “We could earn good money, say, maybe five times more than what we usually earned … so we continued to do this,” he says.

“Those who earned a lot … could buy weekend houses and new cars.”

There is a four-step guide to creating fake news Macedonian-style. Step one: Join a Facebook group using a fake profile.

“It’s important to get into the right groups to post your articles. There are less influential groups and more influential groups,” explains Sasha.

Step two to four are: Find a trending story; rewrite and sensationalise it; post it and profit. “The title is shortened so people can read it at a glance,” he adds.

“News about Trump worked best, especially news that was fake rather than factual, which easily lured people into clicking on the article.”

It was not just clickbait headlines, however, that attracted the eyeballs. Mr Ceselkoski says: “They believe everything you write favourably because they support Donald Trump, and they want to spread the word. They want to share the good news.

“They tag their friends and argue with them, and the story spreads even more.”

That such stories seemed to spread faster than the real ones spoke to issues regarding the media environment, believes Mr Silverman. “It showed that Facebook was rewarding … the most outrageous and the most false content.”

READ: Commentary: Someone needs to do something about Facebook — but what?

WHY FAKE NEWS OFTEN TRENDS

There has been research that may throw light on why people share fake news on social media.

“When they’re receiving likes or looking at content they think might receive likes if they share it … you see activity in the (pleasure centres) of the brain,” cites Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information assistant professor Ben Turner.

“So if you have someone considering whether to share an article or not … when they think about something that’ll make other people like them more … that’ll lead to them being more likely to share information, whether or not it’s true.”

Another team from the same school in the Nanyang Technological University conducted related research by studying whether the quality of hotel reviews online – how well they were written – affected user trust in those reviews.

“Based on our findings, for luxury hotels, regardless of the quality of the review, people trusted the positive review more,” says Dr Alton Chua. “For budget hotels, regardless of the quality of the review, people trusted the negative review more.

“So an implication is this: It’s that confirmation bias sets in (based on) this scenario, where people … expect positive reviews (for the luxury hotel), and for the budget hotel, they expect to read negative reviews.”

Confirmation bias means people tend to look for information that fits what they already believe, even if it is poorly written by trolls.

As senior research fellow Carol Soon from the Institute of Policy Studies says, “Human beings are also creatures of comfort. When we come across a jarring piece of information – something that contradicts our world view – it can cause mental discomfort.”

In a way then, the fake news industry is a product of social media, where people gravitate towards what they agree with, and social media algorithms encourage them to join others who like similar things. This can create echo chambers.

A user who clicks ‘like’ on the page of the far-right Breitbart News Network, for example, is offered more news outlets that reinforce a conservative bias, demonstrates Ms Donara Barojan from the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab in Latvia.

“We can do the same thing with hyper-liberal news outlets such as Occupy Democrats, and we’ll get the exact same results. I’m offered to like Being Liberal, Hillary Clinton's page and a lot of other hyper-liberal media,” she says.

“People get radicalised in their own echo chamber, by not being exposed to the other side’s point of view. It undermines the inter-societal dialogue and further reinforces those divisions that can be exploited through disinformation.”

It is hard, however, for the Macedonian trolls to appreciate the damage fake news can cause.

“Democracy is about free speech of the people. They say it’s fake news, but I think we’re free to speak it,” says “Nikolai”, who was born in Veles.

“It’s their right to read it or not, to accept or not.”

Sasha agrees, adding with a laugh: “You’re not doing any harm; you’re making money … If someone doesn’t like it, he won’t (do it). If you like the idea, you should do it. Trump benefited the most.”

‘INFORMATION OPERATIONS’

Globally, after the Cambridge Analytica scandal in March, when news broke that the political consultancy had stolen the data of up to 87 million Facebook users, there has been a growing sense of urgency of the problem.

Whistleblower Christopher Wylie revealed that during the US elections, there were segments of the population, for example, who responded to messages like, “Drain the swamp” in Washington D.C., or to images of walls.

Using the data, the firm could build profiles of the users and target them with specific election messages.

Byline Media chief executive and co-director Peter Jukes, who was involved in getting Mr Wylie to come forward, tells CNA that people are getting it wrong, however: “It’s not really fake news … It’s information operations.”

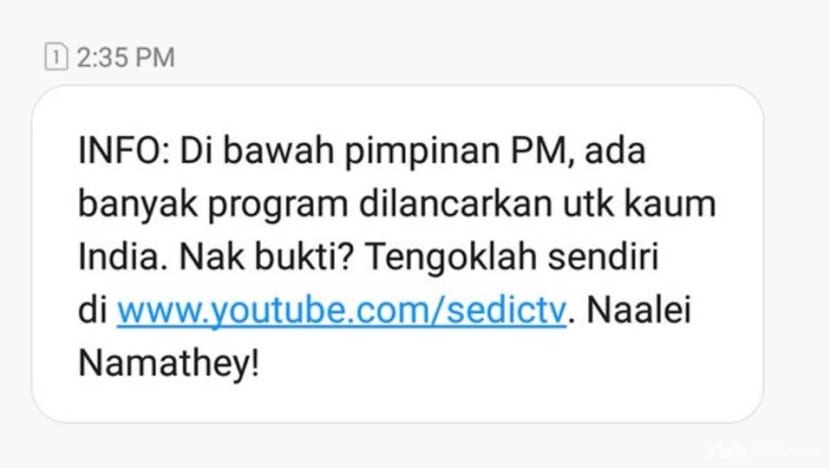

Another case in point is Malaysia. Weeks before its elections in May, a Reuters journalist contacted the Digital Forensic Research Lab halfway around the world to say that she noticed a campaign on Twitter against the Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition.

READ: Ahead of Malaysian polls, bots flood Twitter with pro-government messages

The researchers looked into it and found 22,000 accounts that were using two hashtags: #SayNoToPH and #KalahkanPakatan, which means "Defeat Pakatan" in Malay. According to Ms Barojan, 98 per cent of those accounts were bots, algorithms that do automated tasks.

“We looked at the handles, and they were predominantly alphanumeric handles. That’s a dead giveaway of an algorithm,” she says. “Another giveaway was that they were using the exact same pattern of speech (and) that they had zero followers.”

It can cost as little as US$30 (S$41) to buy a Twitter bot army on the dark web, according to Mr James Chappell, the co-founder and chief innovation officer of analysis firm Digital Shadows.

“Just with some simple software on my computer, I can hire thousands upon thousands of accounts,” he says.

CNA tested this by creating an Instagram account, posting a photograph of a piece of toast and, for a few dollars, managed to buy a few likes and positive comments.

When a tweet or Facebook post has many retweets or shares, says Mr Silverman, “that creates what people call a social proof”.

“It shows that this is resonating, and there’s a desire to kind of join in and be part of that crowd.”

And as the saying goes, a lie repeated a thousand times – by bots or otherwise – becomes truth.

THE INDONESIAN EXPERIENCE

Over in Indonesia, it is now election season, which means things have got busy for fact-checking organisation Masyarakat Anti-Fitnah Indonesia (Mafindo).

Even before Jakarta hosted the Asian Games in August, Mafindo co-founder and head of its fact checker committee Aribowo Sasmito found a fake story involving vice-presidential candidate Sandiaga Uno.

The politician was falsely reported as saying that Indonesia would not be the Games champions because “indigenous athletes are physically weak (and) have low IQs”.

“Mainstream, credible media wouldn’t use such provocative titles,” says Mr Aribowo. “But for people who dislike Sandiaga Uno, they’d simply believe that.”

Politics is one of the most popular topics of fake news in the country, or hoaxes as Indonesians call it, and “usually, political parties would use hoaxes to attack the candidates”, he adds.

One fake story about President Joko Widodo, for example, was that he was a member of the banned Indonesian communist party PKI, with a seeming photo of him at a communist rally in 1965 appearing online.

“This person vaguely looked like Jokowi. But of course in 1965, Jokowi would have been four years old,” notes ANU College of Asia and the Pacific senior lecturer Ross Tapsell.

“But it got spread around because it was so conspiratorial, and it was linked to communism.”

Indonesia also has its troll industry with fake accounts run for profit. These trolls are called buzzers, and one of them, “Iqbal”, tells CNA he has “hundreds” of Twitter accounts and “tens” of Facebook accounts.

He specialises in political posts, and clients pay him to promote content. For the accounts to appear authentic, the posts are tailored to fit the profile’s persona.

“The postings are consistent. For instance, a woman’s profile would discuss women’s issues,” explains Iqbal. He even anticipates future demand by creating accounts that discuss, for example, a politician and his supporters.

“In future, when there’s a client who hires us and is compatible with our account’s back story, the account is already there.”

Business is booming for people like him worldwide. An Oxford Internet Institute study found evidence of social media manipulation campaigns by political parties or government agencies in 48 countries last year, up from 28 countries in 2017.

Iqbal insists, however, that his hands are clean. “Hoax and hate speech in social media these days are a worrying thing. So (my friends and I) usually try to avoid them,” he says.

FIGHTING FAKES

Despite the challenges and complexities in fighting fakes – as Iqbal’s case shows – fact-checking is still crucial. “People believe fake news in Indonesia because, for example, people are lazy,” says Mr Aribowo.

“They just read the title, and then they share it. When they ask the person who sent the news, ‘Is this true?’, the person … would say, ‘I don’t know. I received this from a group, and I shared it.’”

There is, however, a growing call for media literacy education. And change seems to be on its way in Indonesia.

One of YouTube’s Creators for Change is the Cameo Project, six Indonesians concerned about developments that threaten their country’s unity. And they have created a music video called “Cek Dulu”, or Check It First.

“One element that can destroy this unity is hoax or fake news,” says Mr Martin Anugrah, one of the group’s founders.

“Many people don’t find out the facts first, before immediately sharing. For what purpose?”

So the idea behind their video is to teach viewers the importance of fact-checking. Cameo Project co-founder Andry Ganda says wryly: “Life is hard; don’t make it harder.”

Another digital literacy programme in Indonesia is “Think Before You Share”, which is part of the education that youth development group YCAB Foundation offers to disadvantaged children.

YCAB treasurer and chief financial officer Stella Tambunan says social pressure, for example to be the first to post things to friends, contributes to youths sharing “without thinking”.

So her foundation teaches them to be “responsible digital citizens” who can assess whether a story is correct and “whether sharing it means something to anyone”.

“If it doesn’t, then it isn’t worth your time … or your megabyte sharing (it),” she says.

The programme is provided in partnership with Facebook, and the social media giant’s director of community affairs (Asia-Pacific and Latin America), Ms Clair Deevy, is impressed by its engaging way of presenting “what can be a really difficult subject”.

“There's music, and there’s singing, and the young people feel as if they're part of a whole wonderful experience,” she says.

“There’s no way that we can understand every single country and the nuances. So for us, the most important thing is finding local partners.”

Facebook has admitted that it was too slow to fight fake news, but it has started to clean up fake accounts and stories.

Using algorithms, it purged more than 1.5 billion fake accounts between April and September. It has also beefed up data security and changed how its newsfeed algorithm shows content. These measures have had some success.

Macedonian trolls Sasha and Nikolai, for example, have stopped producing fake news. “They’re shutting down our profiles, they’re blocking our shared stories, and also we’re getting (fewer) viewers on our websites. That was the main (reason) for stopping this job,” says Nikolai.

This is a game of cat and mouse, however, and there will be problems associated with fake news for some time.

Ms Barojan says: “It’s important to sustain the public pressure on those social media networks, to make sure they’re not only countering existing threats, but are also preparing for what the future will bring.”

Watch the two-part special The Truth About Fake News here. And read about how fake news fanned the flames of war in Ukraine.