How to help people with autism? It starts by just being a friend

Keith Lee's (centre) befrienders Zhang Ludi (left) and Toh Ee Ming (right) taking a selfie together with the sketches they drew during an excursion to Labrador Park one Sunday morning in December. (Photo: Gaya Chandramohan)

SINGAPORE: “Draw tree!” Keith Lee exclaims repeatedly to his two friends, Toh Ee Ming and Zhang Ludi.

They are seated cross-legged in front of a leafy shrub, trying their best to sketch their surroundings. When a rooster strutting in front of them crows, Keith sticks his head out and responds with his best imitation. Everyone cracks up, including Keith, who lets out a self-effacing chortle.

The first time the trio visited Labrador Park and Keppel Bay area in January this year, they ended up lost and exhausted. Ee Ming and Ludi remember trying to calm down an agitated Keith, who is minimally verbal, from jumping up and down at the taxi stand outside VivoCity mall. People nearby were staring at him, as they waited uneasily for their ride to arrive.

But it’s all part of being friends with a person with autism. And the rewards, the two women promise, outstrip any hiccups along the way.

READ: Hugs and heartaches: Ageing parents stay strong despite challenges raising children with autism

Ee Ming and Ludi are volunteers with Rainbow Centre’s Good Life Befrienders programme, a two-year-old initiative that matches volunteers up with the school’s 15- to 18-year-old students, who have special needs like autism. The aim is for these children to be more accustomed to spending time outside of their family and the classroom as they approach adulthood.

“Our young adults with disabilities struggle with limited opportunities to enlarge their social circles and be included in society,” said Rainbow Centre’s executive director Tan Sze Wee.

There are currently 83 volunteers and the organisation is looking to recruit 30 more in the first quarter of next year. Rainbow Centre is also expanding the programme to clients under their Connected Communities Services, a life-coaching service for people with disabilities between 18 to 35 years old, said Cynthia Lee, Rainbow Centre’s family life service manager and senior social worker.

Studies have shown that autism can be a particularly lonely disability. Dr Eunice Tan, the head of special education programme at the Singapore University of Social Sciences’ S R Nathan School of Human Development, said it is hard for many people with autism to form friendships because of their lack of social skills and inability to read body cues.

The traits they exhibit can also appear alienating. A 2018 study done by two researchers from the University of Virginia and the University of California, Santa Cruz found that four typical autistic behaviours - low levels of eye contact, infrequent pointing, repetitive body movements and echoing previously heard statements - are interpreted as a lack of social interest, even though many autistic people are keen for social connections.

Ludi admits it was difficult for her to connect with Keith when she first met him in January 2019. She and Ee Ming were facilitators at a five-month arts residency and festival called ‘Peekaboo!’, organised by non-profit arts group Superhero Me that was partnering Rainbow Centre.

They were assigned to work alongside Keith in the programme’s theatre project called ‘What Dreams May Come’, which would be staged in March. Ee Ming, 28, was also the festival’s journalist-in-residence and produced stories about how Rainbow Centre served children with disabilities.

They were tasked to do drama exercises that initial meeting. Ludi was confused why Keith wasn’t mirroring her movements, as per instructions. Instead, he was jumping up and down and staring into space, seemingly anxious.

“It was a bit overwhelming for me because I just didn’t know how to (interact with him),” the bubbly 20-year-old medical student said. When she tried to call out to Keith repeatedly, waving her hands vigorously to his face, he ran away and hid behind a pillar, she said.

“I didn’t realise mufflers were there for a purpose,” she said with a laugh, referring to Keith’s earmuffs that help him to cope with sensory overload. He wears them when he goes out.

But she was undeterred by the awkward encounter. They had lunches with Keith and his classmates every time they were at Rainbow Centre, to get comfortable in one another’s presence. They learnt to be satisfied with just receiving a glance from the “gentle giant” - in Ee Ming’s words - as a form of acknowledgement. When he flashed Ludi a smile one day, it was a “woo!” moment.

During her residency, Ee Ming learnt about the befrienders programme. She managed to convince Ludi, who had just started university and was hesitant, seeing it as a way to develop the budding friendship they had with Keith and be a pillar of support in his life after he graduated. He turns 18 on Dec 27.

“I was 19 then, and I was like, ‘what am I going to do for the rest of my life?’,” Ludi said. “Isn’t that what they are facing as well - (the question of) after I graduate from school, what am I going to do?”

Ee Ming, a freelance journalist, had witnessed how people with disabilities face limited work options and a certain degree of social isolation through her work.

“They leave the safety net of a special education school and transition to the world outside. Without proper community support or services, many may end up languishing at home,” she said. “As befrienders, we offer some support and act as a bridge to the wider community.”

The programme pairs volunteers up with students based on common interests, locality and gender (two males befrienders will not be matched with a female student), and allows the group to decide how they would like to spend time together.

WATCH: When your son is 40 and has autism - and you're getting on in age | Video

In Ludi and Ee Ming’s case, they requested to be paired with Keith, and given their introverted personalities, they prefer “more chill” activities away from the crowded shopping malls. The group meets about once a month.

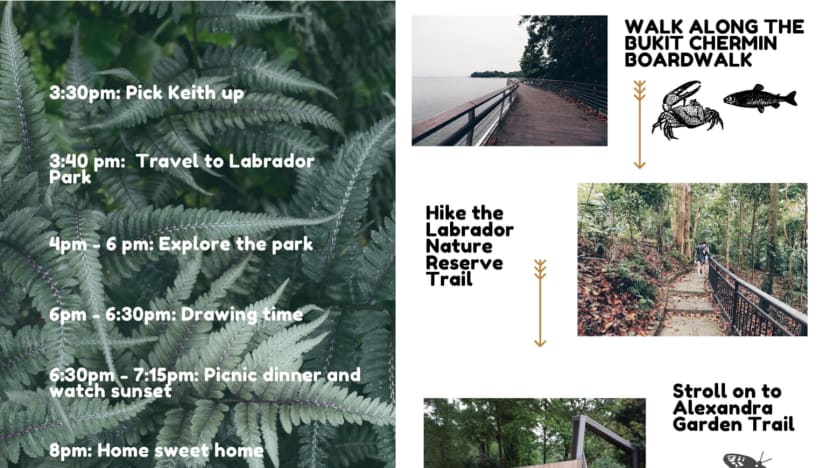

Most of the time, they go for walks, which are free, quiet and suits Keith’s sporty and adventurous nature, said Ee Ming. During each excursion, there are pit stops for snacks, drawing time and selfies.

Their favourite outing took place last November where they explored the Katong neighbourhood and stumbled on hidden gems like an old-school ice-cream distributor at the corner of Joo Chiat Place, climbed the Wallholla vertical playground, and taught Keith how to take polaroid-like photos on his phone. “It was full of unplanned surprises,” said Ee Ming.

Going out with Keith requires more planning than the usual gatherings. Ee Ming, who had observed the Rainbow Centre teachers use visual aids in their classes, would design and print out colourful itineraries to prepare Keith and his parents for each outing.

“If we get lost and we don’t know what the plan is, and we stand there and Google on the spot for fifteen minutes, I imagine that would make him very anxious, seeing us so anxious,” added Ludi. Luckily, there has not been any other near-meltdowns except for the incident at VivoCity earlier this year.

The morning of the second Labrador Park trip, Keith’s mum, Mdm Phoebe Tan, 45, sent a text to Ee Ming: “He was already all up and excited this morning”.

“Let’s say he wants to mingle. Who should we go to? I can’t just ask any stranger, ‘hey, you want to be my boy’s friend?’ (So) it’s a good platform,” added Keith’s dad, Lee Leng Woon, 48.

Keith’s sister, Jess, who is two years younger, said she notices her brother making happy noises and grinning the entire time after he comes home from these meet-ups.

READ: How technology gives my son hope with his autism

“We all could benefit from having advocates in life who appreciate, respect and understand us … so why not persons with disabilities too,” said Rainbow Centre’s Ms Tan. These friendships foster greater understanding of people with disabilities and “is a step towards a more inclusive Singapore,” she believes.

To the cynics, however, volunteer initiatives like these could come across like a self-serving, feel-good affair. Ludi acknowledges they have to keep themselves in check - “whether we are glorifying ourselves” - when they share their experience with others. But the friendship they have with Keith is genuine, they said.

Befriending Keith is also a learning lesson in communication, she said.

“We always use words to express ourselves. But communication can happen in so many ways without verbal words - being observant, body language, writing things down, drawing, visuals,” she said. Sometimes, all the other person needs is to know you are by his or her side.

Spending time with Keith has also brought with it the unexpected pleasure to slow down and enjoy this child-like simplicity and fun.

“The world is so busy, right? We have these moments of peace and quiet, this human connection, which is what we all need,” said Ee Ming.

“We get to do so many things that we don’t usually get to do,” added Ludi.

“I wouldn’t be climbing a playground,” chimed Ee Ming.

For Keith to be taking his time out for the both of them is something to be grateful for as well, they said.

“I always wonder what’s going on in Keith’s mind,” Ee Ming said. “He might be wondering why these two weird girls are bringing me out, always taking selfies with me.” Yet, he cheerfully goes along with every plan they make.

“If there's anything I want to say to Keith … I think, trust is not something that's easy to come by and so thank you for your trust,” said Ludi. “Thank you for letting me be your friend.”