NUH's smallest baby to survive birth discharged after 13 months in intensive care

Born almost four months premature at 212g, Kwek Yu Xuan was about half the expected weight of babies born at her age. Here's how she beat the odds stacked against her.

The Kwek family with Yu Xuan at the National University Hospital. (Photo: NUH)

SINGAPORE: The tiniest baby to survive after being born at the National University Hospital (NUH) has been discharged, after 13 months in the neonatal intensive care unit.

Kwek Yu Xuan beat the odds to survive after she was born almost four months premature at 212g on Jun 9, 2020.

At birth, she was just 24cm long - just about as tall as a bottle of mineral water. When she was discharged from hospital on Jul 9 this year, Yu Xuan's weight was 6.3kg.

Based on the Tiniest Babies Registry managed by the University of Iowa, she is possibly the world’s lightest baby to be born and discharged well to home, said NUH. The previous smallest survivor in the world was born at 245g in the United States.

Yu Xuan’s parents, who are Singapore permanent residents working here, had initially intended to deliver Yu Xuan in Malaysia and reunite with their first child who lives there, a four-year-old boy.

But her mother suffered from preeclampsia and underwent an emergency caesarean section at 24 weeks and 6 days of gestation, startlingly far from the average of 40 weeks. Preeclampsia is a condition where mothers have high blood pressure during pregnancy.

“The challenge actually appeared when we saw her and she was so tiny. It was beyond what we expected,” said Dr Yvonne Ng, who was the neonatal consultant on duty when Yu Xuan’s mother was admitted into the hospital just a day before her birth.

The team had expected her to be around 400g to 500g, said the senior consultant with the department of neonatology at the Khoo Teck Puat - National University Children’s Medical Institute of NUH.

“The first thing that I remember was the difficulty in putting a breathing tube into her. She was so tiny that we had to use a smaller sized tube, 2mm in diameter. The doctor who did it, she had to use her fingers to pry open her mouth gently and put it in, it was quite special,” said Dr Ng.

Yu Xuan’s lower than expected weight could be related to her mother’s preeclampsia and high blood pressure, said Dr Ng.

“We do know that mothers with preeclampsia, hypertension, they do have smaller babies because of poor placental circulation.”

On Jun 8, 2020, Yu Xuan’s mother Mrs Kwek Mei Ling felt abdominal pains after work. After telling her husband about it, they also informed their landlord, who advised them to go to the hospital and helped called for an ambulance.

At the hospital, Dr Ng counselled them on the decision, and shared that premature babies born at 24 weeks had a survival rate of about 70 per cent, though this would also depend on her condition at birth and what happened afterwards.

“We had no idea that I would be giving birth to Yu Xuan so soon,” said Mrs Kwek, adding that she and her husband are thankful to the NUH team for the care they offered.

“At that time, we were very sad that she (would be) born so small. But due to the high blood pressure, we had no choice (but to deliver) ... We are sad but we also have to learn how to move on and help her to grow up,” she added.

“I did not expect her to be so small, because my first boy was natural born at 3.12kg. I also didn’t realise that I had a high blood pressure pregnancy. So it was quite a surprise for us.”

DELIVERING PREMATURELY

Babies born before 37 weeks of pregnancy are considered premature, and they make up about one in 10 births, said Dr Ng. Singapore sees about 3,500 premature births every year.

A baby like Yu Xuan born at 24 weeks and 6 days would be considered an “extremely preterm” baby, said Dr Ng. Between 2001 to 2020, the hospital saw 34 babies delivered at around 24 weeks, of which 24 survived.

The borderline of viability is between 22 weeks and 25 weeks, said Associate Professor Zubair Amin, head and senior consultant of the same department at NUH.

Babies born in this window are “not 100 per cent viable”, and doctors cannot say with confidence that they will survive past birth, he added.

This is because this period is critical for the development of the baby, especially its lungs, which are still maturing, said Assoc Prof Zubair.

“We look at the gestational weight, and also the baby’s age. In Yu Xuan’s case, she was so small that we don’t have any norms to say (what) her chances of survival (were),” he added.

After she was born, Yu Xuan was on a ventilator with a breathing tube for seven weeks to support her breathing. She also had to be fed through a tube, as it was impossible to feed her while she was intubated, said Dr Ng.

The initial part of her stay in the NICU presented the team with some challenges, as it was their first time taking care of such a small premature baby, said Dr Ng.

“We need to look after Yu Xuan very carefully. Because she is so delicate, so small, her skin is so thin, she easily loses water and her skin can be easily broken,” said Ms Zhang Suhe, advanced practice nurse and nurse clinician.

Because Yu Xuan was so small, it was difficult to find space to attach all the necessary equipment or probes to monitor her health, said Ms Zhang.

“Literally, her whole body, we put our measuring devices on her. The skincare is very, very crucial because broken skin means there’s chances of infection,” she added, noting that fortunately, Yu Xuan did not suffer from any infections throughout.

In selecting a breathing tube, even a 2mm difference in size was a big difference because her trachea was so small, and using the wrong tube could cause breathing problems.

Regular diapers were also “huge” on Yu Xuan, so their team had to source for smaller diapers or improvise, said Ms Zhang.

“We do face a lot of challenges in terms of medical care, nursing care. Fortunately, we actually overcome them one by one with all the brainstorming, daily thinking about what is best for Yu Xuan.”

When she was about 678g, the doctors removed the tube and instead used nose prongs with the ventilator. By then, she was breathing on her own, and the ventilator was providing additional oxygen support.

In the later months of her stay, she developed more like a regular preterm baby, and the team could offer her routine care, said Ms Zhang.

WHAT’S NEXT FOR YU XUAN

Yu Xuan’s 13-month stay in the NICU also makes her the longest staying baby in NUH’s unit, said the hospital.

Despite the odds stacked against her with health complications from birth, she was active, cheerful and responsive while she was in the hospital, the team said.

Before premature babies are discharged, doctors will make sure that they are stable enough to go home, and that the family is comfortable with taking care of them, said Dr Zubair.

Parents also need to be trained on how to use the equipment and how to respond in different situations, he added.

“The discharge was really huge, huge work put in by every one of us. Her parents are very ‘on’; they are very willing to learn whatever we have identified for them” said Ms Zhang.

The doctors and nurses took charge of training her parents in different aspects of her care, in preparation for her discharge. “We put together rehearsals. We even rehearsed how to transport (Yu Xuan), because we anticipated she needs to come back to the hospital with all the equipment,” she added.

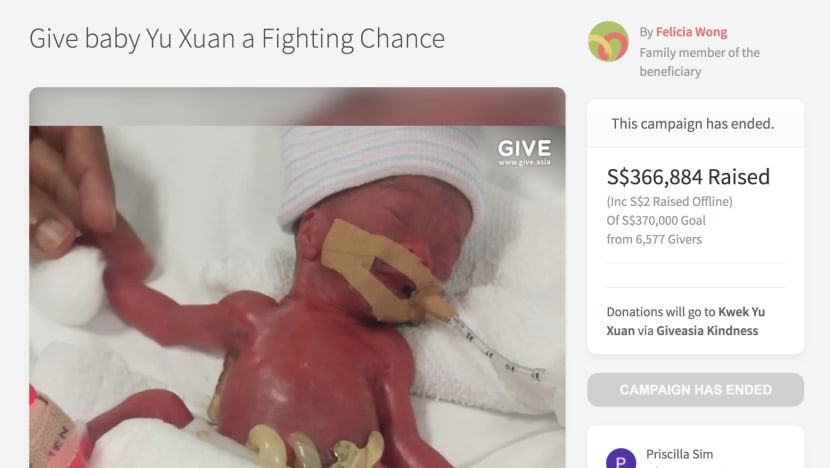

The total cost of Yu Xuan’s stay was about S$230,000, said Mrs Kwek. A Give.asia crowdfunding campaign that she launched last year raised S$366,884 for her baby’s case.

On top of the S$230,000 used for Yu Xuan’s stay in the NICU, the couple kept another S$56,000 to fund the rest of Yu Xuan’s treatment and recovery. And they donated S$50,000 to Give.asia to help other families in need.

“On the discharge day, the whole team of residents and doctors, we were all very, very happy for her, happy for the family,” said Ms Zhang, adding that even some members of the team who were not on duty came to take photos and see her off.

Yu Xuan currently needs to return to the hospital for follow-up check ups once a month. She has chronic lung disease and pulmonary hypertension - two conditions commonly associated with extreme prematurity - but is expected to get better with time, said her doctors.

Premature babies past 36 weeks who still need a ventilator are ascribed to have chronic lung disease, said Dr Ng.

Aside from the oxygen support from the ventilator, Yu Xuan also takes medicine for her chronic lung disease, such as diuretics to help her urinate more.

“A lot of 24-weekers have come through our department, and they generally have the same types of long-term conditions that she has,” said Dr Ng.

“We have many with chronic lung disease, many who had ROP (retinopathy of prematurity) treatment, and we’re all hopeful that they will eventually outgrow these problems and grow up to be healthy children.”