COVID-19 White Paper: U-turn on masks, confusing measures among areas Singapore says it could have done better

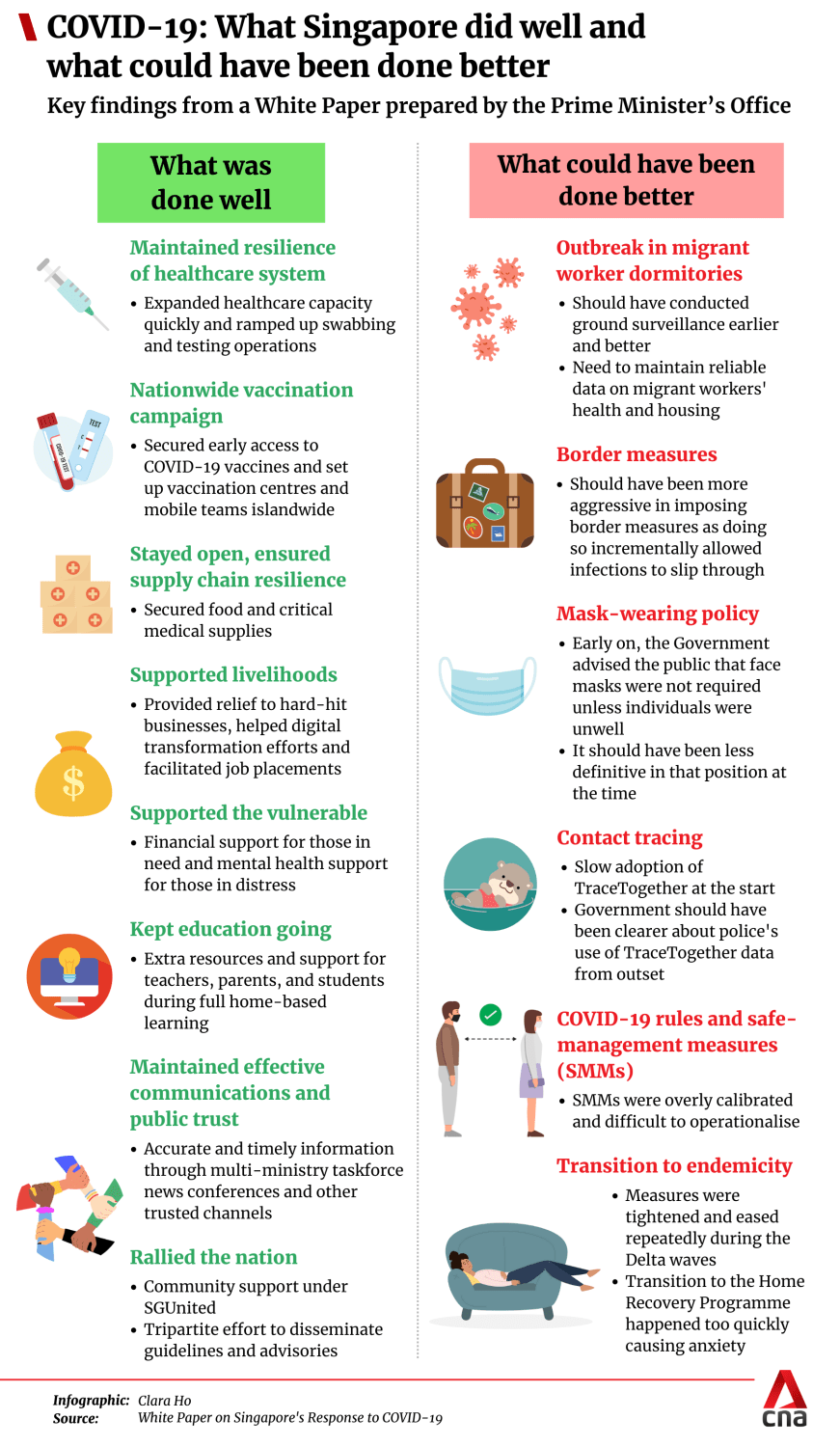

The Government could also have better managed the outbreak in migrant worker dormitories, border measures, contact tracing efforts and the transition to endemic COVID-19, according to the White Paper.

SINGAPORE: Singapore’s mask-wearing policy early in the pandemic and safe management measures that confused the public were areas in which the Singapore Government could have responded better to COVID-19.

These were among the conclusions of a White Paper on the Government’s review of its pandemic response published by the Prime Minister’s Office on Wednesday (Mar 8).

Six areas where the Government could have done better were identified, including the outbreak in migrant worker dormitories, border measures, contact tracing and the transition to endemic COVID-19.

The White Paper drew on a review conducted by former head of civil service Peter Ho, which included interviews with ministers and civil servants.

The White Paper also includes findings of reviews by various government agencies and perspectives from the people and private sectors.

Speaking to reporters, Deputy Prime Minister Lawrence Wong said COVID-19 has been “a very complex and wicked problem on a grand scale”, requiring the Government to operate in the “fog of war”.

“We made our best judgment at that time, but of course, with the benefit of hindsight and what we know today, we probably could have handled certain situations differently," he added.

He added that this review was separate from an audit of some of the Government expenditure to fight COVID-19. The audit is being undertaken by the Auditor-General’s Office.

The White Paper will be debated at the next sitting of Parliament on Mar 20.

U-TURN ON WEARING MASKS

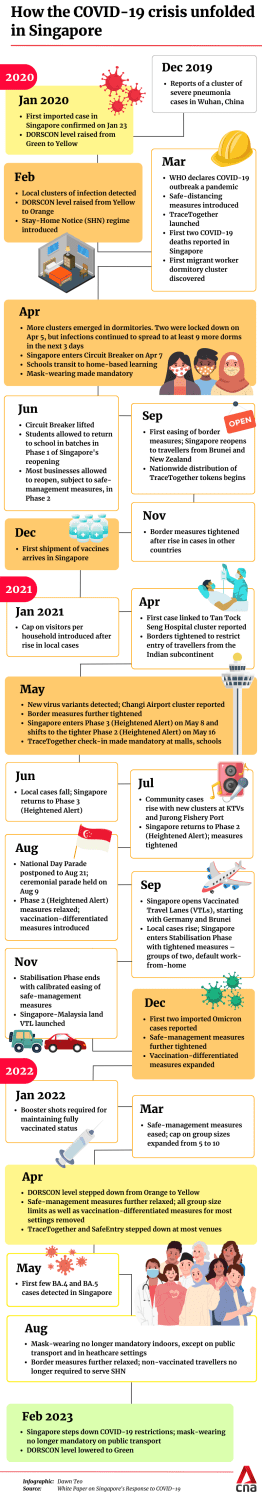

Singapore confirmed its first case of COVID-19 in January 2020. In the initial stage of the pandemic, the Government advised people not to wear a mask unless they were feeling unwell.

But after investigations found that virus transmission could occur before the onset of symptoms, it became mandatory to wear masks in public in April 2020.

“The public viewed the change in mask-wearing policy as a U-turn contradicting the Government’s earlier position. This undoubtedly affected public trust and confidence in our handling of the crisis,” stated the White Paper.

“On hindsight, as the clinical evidence on COVID-19 was still evolving and before we learnt how easily the virus spread, we could have been less definitive in our position on mask-wearing.”

The White Paper also found that the Government could have encouraged people to make their own masks while the production of surgical masks was being ramped up.

Explaining the Government’s thinking at the time, the White Paper found that the evidence for pre-symptomatic or asymptomatic spread did not emerge early enough for it to “optimally manage” the situation.

A mask shortage and panic buying complicated matters. Singapore’s stockpile of surgical masks was depleting rapidly and was insufficient for daily mask-wearing by the population.

The depleting stockpile of masks, as well as prevailing guidance by the World Health Organization (WHO), informed the Government’s initial stance, the White Paper stated.

CONFUSING SAFE MANAGEMENT MEASURES

As Singapore reopened, some safe management measures were “overly calibrated” as well as “overly elaborate, difficult to operationalise and explain, and therefore confused the public”.

“All this highlights the need for us to exercise greater flexibility in a crisis, go for broader brush but more implementable measures, and to guard against the instinct to aim for unrealistic standards of perfection,” the White Paper stated.

It highlighted the different rules for physical activity, which depended on the level of exertion and whether it was indoors or outdoors, and the various measures around wedding receptions.

While the intention was to "carve out exceptions" for important life events, the rules “tended to emphasise precision over simplicity” and were often too complicated, stated the White Paper.

During and immediately after the “circuit breaker” in 2020, there was also “some unevenness in treatment” when rules were defined for specific businesses.

Fine distinctions made in the list of essential services allowed to operate were not always consistent, and caused some businesses and workers to be unhappy at not being considered “essential”.

For example, the public highlighted the discrepancy of not allowing home-based businesses and bubble tea shops to operate even though they did not pose significantly more risk than other takeaway-only eateries.

Traditional Chinese Medicine workers were also excluded from mask distribution to healthcare workers as they were not considered to be part of the healthcare sector.

OUTBREAK IN DORMITORIES

The outbreak in migrant worker dormitories grew acute from April to August 2020, with hundreds of new cases reported every day.

By the end of 2020, nearly half of about 300,000 workers living in dormitories had been infected. There were two fatalities.

This was a “crisis within a crisis” and the early precautions taken in dormitories were insufficient, the White Paper concluded.

“Given the communal living environment, the dormitory outbreak had every possibility of becoming a major disaster. We should have probed deeper and conducted better and earlier ground surveillance, such as by doing dipstick testing on sample populations to make the most of limited testing resources.”

When the first dormitory case was detected in February 2020, the Government followed procedures instituted after the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak in 2003.

Aside from the prevailing view that asymptomatic transmission was not possible, the Government also lacked a consolidated picture of migrant workers who had sought treatment from different service providers for acute respiratory infection symptoms.

“Without a clear picture of the health risks, we were unable to justify taking the drastic step to restrict movements from and within dormitories,” stated the White Paper.

The Government was also hampered by the limited testing capability at the time and the lack of integrated access to migrant workers’ health records.

“We could not track the outbreak in a comprehensive and timely way. This hampered our ability to identify and isolate infected individuals before they infected others,” the White Paper stated.

The outbreak in dormitories was eventually contained after testing capacity was ramped up and quarantine facilities were set up.

A “difficult judgment call” then had to be made about relaxing movement restrictions in dormitories. After most workers were vaccinated and boosted, some restrictions could have been eased earlier.

The Government acted with an “abundance of caution”, but extended restrictions took a toll on workers’ mental well-being, it noted.

The need to maintain more reliable and accurate information on the migrant worker community outside of a crisis, and more comprehensive medical support for migrant workers were the key takeaways from this experience.

BORDER MEASURES

When the Government started introducing border closures progressively from January 2020, it calibrated these in an attempt to protect Singapore’s air hub status and to strike a balance between saving lives and livelihoods.

"On hindsight, at the beginning we should have built in a margin of safety and tightened border measures more aggressively the moment there were signs of the virus spreading across borders, even when there might have been some risk of us overreacting to these signals," stated the White Paper.

It added that the Government might have been “overly anxious about preserving the functioning of our economy and jobs”.

The White Paper singled out two occasions. The first was when Singapore restricted entry progressively on a country-by-country basis as the global situation worsened through February and March 2020.

The second was during the spread of the Delta variant in 2021, when Singapore closed its borders to India as infections shot up there. It was slower to do so for other countries in the Indian sub-continent and countries with high travel volumes from India.

The White Paper also found that the Government could have let long-term pass holders back into Singapore sooner, or at least prioritised entry for some groups once the local infection situation was stabilised.

While the entry suspension for long-term pass holders was not done without reason, it created significant difficulties for this group, who endured prolonged family separation and disruption to their work.

“Singapore incurred reputational cost and lost some goodwill from this segment of the community who also had their homes here,” stated the White Paper.

It also acknowledged the limits of border measures.

"Once the virus starts spreading locally, border measures are no longer effective or relevant, although they may still provide psychological reassurance and be a useful signal of caution."

Education of the public on the role of border measures in infection control was needed, so people can better appreciate what the measures could and could not achieve.

This would help Singapore implement border measures that better matched the prevailing risk and public health situation.

TRACETOGETHER AND SAFEENTRY

The launch of the TraceTogether app and token and SafeEntry check-in reduced the time needed to identify and quarantine close contacts from four days to less than one-and-a-half days.

But the TraceTogether app took several months after its launch in March 2020 to actually make an impact on contact tracing efforts, because its effectiveness depended on widespread adoption of the app.

This only came about when the tools were integrated through TraceTogether-only SafeEntry, which became mandatory at higher risk venues from June 2021, the White Paper stated.

“This shows that beyond developing the technology, we have to integrate the technology well with operational plans, and to tackle adoption challenges,” stated the White Paper.

The TraceTogether programme also suffered a setback in January 2021 when it was disclosed in Parliament that the data can be used by the police in criminal investigations, contradicting earlier reassurances that it would only be used for contact tracing.

“This error naturally caused unhappiness and affected public trust,” stated the White Paper. “The Government should have been clearer about the use of TraceTogether data from the onset.”

Related:

TRANSITION TO ENDEMIC COVID-19

The multi-ministry task force first mooted the possibility of endemic COVID-19 in May 2021, just as the Delta variant hit.

To manage the Delta variant, safe management measures were repeatedly tightened and eased over the second half of 2021, leading residents to become “understandably frustrated”, stated the White Paper.

“While some felt we should have gone into a full lockdown, others questioned our resolve to live with COVID-19 as endemic.”

It noted that some people felt the Government was “constantly shifting goal posts for reopening” by citing different measures, such as vaccination rate targets, weekly infection growth rates, intensive care utilisation rates and hospital bed occupancy rates.

“In reality, it was trying its best to respond to the changing nature of the virus, while trying to avoid overwhelming the healthcare system.”

The White Paper also acknowledged the “teething issues” with the home recovery programme. This was supposed to be launched first as a pilot, but soon became the default mode of recovery for more people in September 2021.

“The change happened too quickly. The sudden recharacterisation of COVID-19 as a disease mild enough for one to recuperate at home was too unsettling for many to accept,” stated the White Paper.

This caused uncertainty and anxiety among patients and their families, and a surge of people called government hotlines, overwhelming them.

LESSONS FOR THE NEXT PANDEMIC

The White Paper identified seven lessons for future pandemics and other national crises.

First, when dealing with a complex crisis, the Government must “establish upfront which dimension to prioritise”, including being clearer on the prioritisation between public health and economic considerations.

It must also exercise more flexibility and not allow “the perfect to be the enemy of the good”.

Second, the Government must strengthen Singapore’s resilience to be better prepared for disruptions and bounce back from shocks. As part of this, it will review stockpiling strategies.

Third, the Government can do more to harness the strengths of the people and private sectors, and must develop an ecosystem to nurture these relationships in peacetime.

Fourth, strong public health expertise and organisational capacity must be systematically built up, with expanding healthcare capacity a key aspect of this.

Fifth, the use of science and technology in pandemic crisis management must be institutionalised. This means investing in interoperable data systems and engineering capabilities, as well as ensuring cybersecurity.

Sixth, the Government must strengthen its structures and capabilities for forward planning to respond more agilely and fluidly.

“While the lessons will help give us a better sense of preparedness, we must never fight the last war," said Mr Wong, who was also co-chair of the COVID-19 multi-ministry task force.

"We must not allow the lessons to become hard coded into a certain doctrine that might lead us down the wrong path, especially if the next virus turns out to be very different in character and nature from what we have experienced so far."

Lastly, the Government must continue putting out transparent and clear public communications to build trust and ensure an effective response in a crisis.

Editor's note: This article has been updated to reflect that the review by the Auditor-General's Office is only for some of the Government's expenditure to fight COVID-19, not the full S$72.3 billion.