Dementia stole his golden years. His family donated his brain for research so others wouldn't suffer too

In Singapore, brain donation is separate from the Human Organ Transplant Act (HOTA), which Singapore citizens and permanent residents are automatically included in.

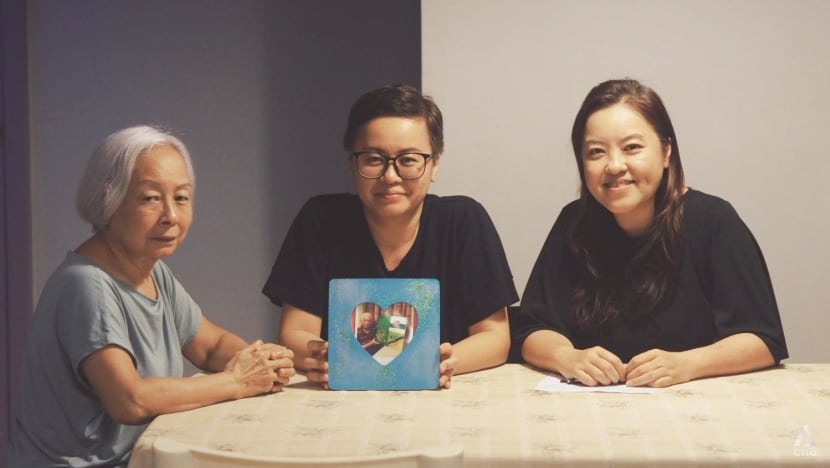

Mdm Violet Ow and her two daughters, Vince (middle) and Vivian, with a photo of Mr Yip, whose brain was donated after his death two years ago. (Photo: CNA/Grace Yeoh)

SINGAPORE: In the advanced stages of the late Albert Yip’s dementia, his family signed his brain away.

The Yip family pledged his brain for donation just before he died in 2020 at the age of 73, in hopes that contributing to brain research would mean fewer people would go through the same suffering they did.

Mr Yip retired from being a taxi driver before he started showing signs of dementia in 2018. He would lose his way while out buying food or sending his grandchildren to school. And he wouldn’t pick up his phone when his family called.

Mdm Violet Ow, his wife, chalked up this carelessness to his “usual behaviour”, the 71-year-old told CNA in Mandarin. But a visit to the doctor’s in early 2019 revealed that her husband had, in fact, been suffering from dementia for five to six years.

The news hit their close-knit family hard, shared Mdm Ow’s daughters, Vince and Vivian Yip.

Vince, who lives with her own family, felt “a little bit guilty” that she hadn’t spotted signs of her father’s deterioration.

“It didn’t occur to me until my mum and I brought him to the polyclinic. He wasn’t even able to answer, even basic things the doctor was asking, like what year it was. That’s when I realised how severe it was,” said the 44-year-old, who works in business development.

RELATIONSHIP CHANGED AFTER DIAGNOSIS

As Mr Yip’s dementia worsened in the later half of 2019, he “turned into a totally different person”. Even the doctors said so, recalled Mdm Ow.

Vivian said her late father was generally mild-mannered, and although he could be quick-tempered on occasion, he never lashed out at the family.

“But (with dementia), we see him getting frustrated. There was one incident that really scared my mum because he suddenly just shouted. Very, very loud, and very, very angry. We were having dinner and he suddenly lost it. But that person is not him,” said the 46-year-old, who works in human resources.

While Mr Yip spent his days at the Alzheimer’s Disease Association (renamed Dementia Singapore in 2021), the centre had to be shut during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Staying home resulted in communication problems with his family.

“There was a point where we didn’t want him to move around because he was not very stable. So we had a wheelchair. I know he didn’t like sitting there, and he just wanted to keep getting up. He kept asking: ‘Why are you doing this to me?’” said Vivian, tearing up.

“We had to tie him down. Which is … it’s painful to do this."

NO HESITATION FOR BRAIN DONATION

And then Mdm Ow came across an article on brain donation in Chinese-language newspaper Lianhe Zaobao. She thought it would be a good idea to register her husband as a brain donor, and her daughters had zero reservations too.

In September 2020, just two months before his death, Mr Yip was registered with Brain Bank Singapore (BBS), the first tissue bank in Southeast Asia dedicated to the repository of human brain tissue to study various neurological disorders.

Neurological disorders affect the brain, spine, muscles and nerves. They include diseases such as dementia, stroke, Parkinson’s disease, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis and motor neurone disease.

As of Jun 1 this year, BBS had 172 registered brain donors. Four registered donors have since died and their brains were donated.

“When I came across the brain donation article, I thought about how my husband already has dementia. What if, in the next 10 years, there are more people above 65 who have the same condition? What if our next generation also has this?” said Mdm Ow.

“I’m unlikely to benefit (from the donation of my husband’s brain), and so are my children. But my grandchildren might benefit from medication or research that is done on the brain to cure dementia.”

“Anyway, after you die, you don’t have any more use. Of course, most people think that you must retain your ‘complete’ body, but that’s a waste," her daughter Vivian added. "Who knows, my tiny contribution could help. What is important is the present. After someone passes, what’s left?”

Mdm Ow also believes her late husband would have willingly signed up to be a brain donor, as he believed in helping others in whatever ways he could.

“When my brother said, ‘Now he doesn’t have a brain’, I told him, ‘Well, he doesn’t need a brain!’” she said, with a chuckle.

Can anyone register to be a brain donor?

Interested individuals need to be above 21 years old.

BBS is not able to accept donors who have infectious diseases like HIV, hepatitis and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease to prevent transmission to researchers who study these human biological materials, said Dr Joan Sim from BBS.

Additionally, brain donation will not be able to proceed if there is a delay of more than 48 hours after death, because “there will be degradation of the tissues which makes them not useful for in-depth research studies”, she added.

Brain donation is also not possible when a patient on life support has been declared brain dead, due to the extent of tissue damage.

EARLY DETECTION AND DIAGNOSIS CRUCIAL

Brain donation can help with early detection and diagnosis, as there is often a “window” period for some neurodegenerative disorders like dementia where medication, therapy and rehabilitation can help with the symptoms at an earlier stage, noted Dr Adeline Ng, a senior consultant of neurology at the National Neuroscience Institute (NNI) and deputy director at BBS.

It also “allows patients and their families more time to plan for the future”, she added.

Studies have shown that Asian and Caucasian brains present different clinical symptoms in the same neurological disorder, although its reasons are still unclear, said Dr Ng.

There are also demonstrated differences in brain structure between different Asian ethnic groups, so collecting a repository of brain tissue from these groups is important, she added.

Brain donation can also help doctors better understand mental illnesses.

“Much like Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease, psychiatric disorders are inherently difficult to study unless we have access to the affected brain tissues,” noted Dr Jimmy Lee, a senior consultant with the Department of Psychosis and Research Division at the Institute of Mental Health.

Being able to study brain tissue will “provide insights into why individuals are affected differently” by the same psychiatric conditions, such as schizophrenia, major depressive disorder or bipolar disorder, added Dr Lee.

After all, different individuals could display “more severe symptoms” or respond differently to similar treatment.

Illustrating how current research into the brain has helped doctors understand neurological diseases better, Dr Yeo Tianrong added that it is now possible to “simultaneously interrogate thousands of genes” from the brain of someone with Alzheimer’s disease to work out which genes have been “turned on” and which have been “turned off”.

Researchers can even do that with each individual cell within brain tissues, providing them “a signature of how the cells in the brain have been changed by the disease”, said the senior consultant of neurology at NNI and deputy director designate at BBS.

Dr Yeo said studies have also shown that cells in the immune system may be “potentiating brain injury” by making neurons more vulnerable to dying.

“(This is) an important insight … so drugs which target immune cells, rather than cells in the brain, are now being considered for clinical trials to slow down or stop dementia.”

BRAIN DONATION SEPARATE FROM HUMAN ORGAN TRANSPLANT ACT

One very real hurdle to persuading more people to sign up is that brain donation is separate from the Human Organ Transplant Act (HOTA), which Singapore citizens and permanent residents are automatically included in. And this separation “can be a challenge (to) any individual’s beliefs”, said Dr Sim, a manager at BBS.

Brain donation also does not fall under the Medical (Therapy, Education and Research) Act.

As brain donation to the BBS is “only used for the purpose of biomedical research and is not used for transplantation or medical education”, brain donation is included under the legislation of the Human Biomedical Research Act and Human Tissue Framework.

Interested individuals have to complete a consent form with BBS to register as a brain donor.

“It is harder for people to understand the impact of brain donation for the benefits of biomedical research, as such work is long term and takes years to generate discoveries for better treatments for future generations,” added Dr Sim.

“BBS tries to overcome this challenge of an individual’s belief by raising awareness that there are no cures for brain disorders like dementia, motor neuron disease and psychiatric conditions to date. The management of symptoms that interfere with daily lives relies on current drugs which may not be very effective.”

Neurologically speaking, the lack of research done on the brain can be mainly attributed to the “complexity of the human brain and the inaccessibility of the brain for biomedical research”, added Dr Yeo.

Even though the advancement of technology in MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) has allowed doctors to gain insight into the brain’s structure, he noted that these measures are still “surrogates” of the actual brain and disease processes.

“Thus, for neuroscience research to advance, we need to study the disease process in human brains – which can only be provided through donation after death,” he said.

MISCONCEPTIONS, TABOOS

Misconceptions about brain donation and taboos surrounding death continue to persist.

For starters, there is the myth that brain retrieval takes place at the forehead, said Dr Sim from BBS.

This misconception often stokes fear in a grieving family that brain donation “would disfigure the deceased’s face or result in their hair being removed”, making it difficult to have an open-casket funeral.

“This is not the case. The face remains untouched as the brain is retrieved from the back of the head, stitched up neatly afterwards and the area is covered by the deceased’s hair … to ensure minimal effect on the appearance of the body,” explained Dr Sim.

“Neatening up of the cut will also be done by BBS’s engaged casket company before the body is returned to the family for the funeral. Open-casket funerals can proceed as normal.”

Death also remains a taboo subject in Singapore, added Dr Sim. “Therefore, while individuals may be interested to register as brain donors, it can be challenging to discuss their end-of-life plans and wishes with their family or loved ones.”

But when such open conversations take place during the process of drafting their wills and Advanced Care Planning, it allows the individual to “reflect on the legacy they want to leave behind”, she said.

Brain donation is then seen as a “natural next step” in ensuring they can continue to make a difference in the lives of future generations after they pass on.

“It is difficult to imagine the depths of frustration caused by neurodegenerative conditions which do not have a cure currently, such as dementia, Parkinson’s disease and motor neuron disease, unless you or a loved one has suffered from one,” said Dr Sim.

Several donors have shared that “they want something good to come from their illness”, she added. By donating their brain for research, they hope to “help find a cure for or even prevent other patients from suffering these brain disorders”.

This, too, is the philosophy that guides the Yips. Being able to contribute to the future is their way of doing their best in the present.

“It is not about that change happening in this life,” said Vince.

“Having gone through this process, it's just about sharing our experience. Not only the caregivers’ pain, but also what my dad went through. He was about to retire and had dementia rob him of everything else, of whatever remaining years he could have had,” she added.

“It’s something that you wouldn't want anybody to go through.”